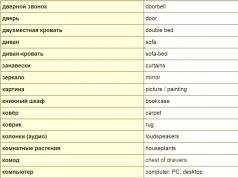

I bring to your attention fragments of a documentary film about Fonvizin, a presentation for the system of lessons on the comedy "Undergrowth", audio files.

Lesson 1. "Undergrowth" as a satirical comedy. The plot and conflict of comedy.

1. Fonvizin and his comedy

Implementation of homework

What main stages of Fonvizin's life did you note when doing your homework? (Born in Moscow in a family of Russified Germans, studied well at the gymnasium at Moscow University, moved to St. Petersburg, knew Lomonosov, became interested in theater. He began his literary career with translations of fables and plays. Then he worked as a translator at the College of Foreign Affairs. Fonvizin's first play "Brigadier". He was Panin's close associate, whom Catherine 2 hated. "Undergrowth" was first staged on September 24, 1782. But Fonvizin then had to retire. Wrote the satire "General Court Grammar", after which he was banned from printing. Then it's hard fell ill and died at the age of 47.)

Let's watch the videos and answer the questions (slides 2-4)

Slide 2. Pedigree. Childhood (watch video)

What is the origin of the surname Fonvizins? (of German origin).

When did they appear in Russia? (Ancestors of Fonvizin ended up in Russia during the reign of Ivan the Terrible, during the Livonian War)

Where was Fonvizin born? (in Moscow)

Who is it named after? (in honor of his ancestor Denis)

Where and how did he study? (he studied at the gymnasium at Moscow University perfectly)

Slide 3. Comedy "Undergrowth"

What shortcomings does Fonvizin denounce? (flattery, servility, savagery and cruelty of serfdom)

In whose mouth did he put his secret thoughts? (In the mouth of Pravdin and Starodum)

Slide 4

Where was the comedy first staged? (In the old theater on the Tsaritsyn meadow)

What did Prince Potemkin say to Fonvizin after the release of the comedy? (“Die, Denis, you won’t write better!”)

What did the writer condemn in comedy? ("evil-mindedness is a worthy fruit")

What used to mean the word "undergrowth"? (the so-called nobles who did not reach the age of majority)

2. Announcement of the topic of the lesson, goals, problems.

The subject of our today's conversation will be a comedy by D.I. Fonvizin "Undergrowth",

And the goal is to resolve the problem “What should a true nobleman be like and whether the Russian nobility corresponds to its purpose”.

3. Quiz on the knowledge of comedy.

Where does the comedy take place? (on the estate of Prostakova)

Ø Who is Prostakov's social background? (noblewoman, landowner)

Ø Who is Prostakova Skotinin? (brother)

Ø Who is Sophia Prostakova? (pupil, distant relative)

Ø Who is Sophia Starodum? (uncle)

Ø What are the names of Mitrofan's teachers? (Tsifirkin, Vralman, Kuteikin)

Ø Who is Eremeevna? (nanny Mitrofan)

Ø What is the name of Sophia's fiancé? (Milon)

Ø Who is Pravdin? (representative of the law, who came to clean up the estate of Prostakova)

Ø What is Mitrofan's favorite pastime? (chasing pigeons on a dovecote)

Ø How many suitors does Sophia have and who are they? (Milon, Skotinin, Mitrofan)

Whose words belong to:

o "And you, cattle, come closer." (Prostakova)

o “At night, he kept asking for a drink. I deigned to eat a whole jug of kvass. (Eremeevna)

o “I love pigs ... and we have such large pigs in our neighborhood that there is not one of them that, standing on its hind legs, would not be taller than each of us with a whole head.” (Skotinin)

o “Read it yourself! … I can receive letters, but I always order someone else to read them.” (Prostakova)

o “An ignoramus without a soul is a beast. The smallest feat leads him to every crime. (Starodum)

4. Comedy analysis.

Slide 5. Let's remember the theory!

What is satire?

This is one of the types of comic, ridiculing and denouncing social vices.

What is comedy?

This is a genre of drama that ridicules human or moral vices.

What are the problems of Fonvizin's comedy?

1. What should be a true nobleman - and does the Russian nobility meet its purpose?

2. The need for enlightenment, education - their absence ..

3. Lawlessness of the peasants and the arbitrariness of the landowners.

DW: There are two storylines in comedy. One resolves a love conflict, the other - a social, moral one. Let's draw the events of these two conflicts.

T.P. Makogonenko: “The artistic innovation of Fonvizin manifested itself in “The Undergrowth” ... in a plot that reveals the main historical conflict ...”

Is there a love affair in the play? (Yes. And outwardly the action is based on a love conflict.)

The resolution of the love conflict occurs, as it were, from the outside, by Starodum: it connects Sophia and Milon. The virtuous hero wins.

But Fonvizin's love conflict is not the main one. The story of Sophia's misadventures is only the background against which the main conflict of the play is played out - the socio-political one.

· Between whom there are serious disagreements? Which?

Between feudal lords and enlightened nobles (the world of evil - reason, malevolence - virtue, arbitrariness - law). To trace the development of this conflict, one must again turn to the plot, which Fonvizin builds masterfully. It turns out to be multi-level, multi-structural, hence several storylines:

So, one of the problems raised by Fonvizin was the problem of how to educate a real citizen. Fonvizin shows us Mitrofan's teachers. Tell about them.

Checking individual homework

1. The story of Tsifirkin

2. The story of Kuteikin

3. The story of Vralman

Ø One of the ways to create a comic was the use of "talking" surnames. What do teachers' names say? (Tsifirkin - this surname hints at the specialty of a mathematics teacher. Kuteikin - from the outdated word "kutya" - church food, a hint that Kuteikin comes from church ministers. Vralman is a sharply negative characteristic, hinting that the bearer of such a surname - liar)

Ø It is said about Mitrofan's "exam" that in this scene there is a clash of true enlightenment and militant ignorance. Do you agree with this? Why?

Ø Who can be brought up by such ignorant teachers? Can they bring up a true citizen, a good nobleman, an educated person?

Ø How does Prostakova relate to the education and upbringing of her son? (Insanely loving her son, she tries to protect him from teaching so that Mitrofanushka does not overwork. In an effort to make a favorable impression on Starodum, she says to her child: “You at least learn for the sake of appearance, so that it comes to his ears how you work, Mitrofanushka ...” Mathematics for her is “emptiness”, “stupid science”; geography is also not needed - “the coachman will take you where you need to go anyway ...”. She is sincerely convinced that sciences are not needed, since “even without sciences people live and lived ...”)

Ø Is she educated herself or not?

Ø Why does a true nobleman need to be educated?

Ø Why do you think the comedy begins with the scene with the tailor Trishka?

Ø What do we learn about life in the Prostakovs' house when we carefully read the 1st act?

Ø What do we learn from Prostakova and Skotinin about their relatives?

Ø What is the relationship between family members? (from a position of strength).

Ø What is the relationship of nobles to serfs? (d.5 yavl.4,5; d.1 yavl.4), the interests of the landowners?

Ø What is the purpose of negative characters? Show what and how should not be.

The problem of a true nobleman is also demonstrated in the monologues of Starodum. Starodum is a character expressing the author's position. Such a character was called a reasoner.

Checking individual homework:

Ø Tell us what Starodum is talking about, what vices does he denounce in his monologues?

Homework:

1. Fill in the table of Prostakova's speech characteristics. (*Slide 12) (Individual task: dramatization of 1-4 phenomena of 1 action)

2. Learn the definitions of satire and comedy

Lesson 2

1. Checking homework

Ø Speech characteristic is the main means of creating an image in a dramatic work. Why?

Ø What words prevail in Mrs. Prostakova's speech?

Does she speak the same way to everyone? With whom and how?

Ø Read out what words prevail in her conversation with different people

Ø Depending on the situation, she can speak differently with one person. Prove it

Ø What conclusion can we draw from Prostakova's speech characteristics about the qualities of her character?

Ø And what conclusion about Fonvizin as a playwright can we draw?

2. The word of the teacher. Lecture recording.

“More than two hundred years have passed since the first performance of The Undergrowth, but Fonvizin’s comedy is successfully taking place on the stage of the modern theater, which means that the “river of time in its striving” has not swallowed the play of the eighteenth century. And we explain this phenomenon by the fact that the play created in the era of classicism, which absorbed its features, thanks to the talent of the author, went beyond the framework of classicism, taking a very special place in Russian dramaturgy. Today we will reveal the features of classicism in it, and also find those features that distinguish comedy from classic works.

But first you need to get acquainted with classicism as a direction of literature.

In literature and art, there are such directions:

1. Classicism

3. Romanticism

4. Realism

5. Modernism

Classicism is an artistic system that has developed not only in literature, but also in painting, sculpture, architecture, landscape art, and music. This is what we will talk about today.

(* problem statement: fill in the table with answers)

Classicism took shape in the 17th century in France, reflecting the rise of absolutism, or absolute monarchy.

The very name classicism (from lat. Сlassicus - exemplary) emphasized the fact that the artists of this trend inherited the ancient “classics”. But the classicists did not take everything from the Greeks and Romans, but only what they considered the embodiment of order, logic, harmony. As you know, ancient architecture is based on the principle of straight lines or a perfect circle. Classicists perceived it as an expression of the priority of reason, logic over feelings. Ancient art impressed the classicists also by the fact that patriotic, civic themes were widely represented in it.

The principles of classicism

The basis of everything is the mind. Only that which is reasonable is beautiful.

The main task is to strengthen the absolute monarchy, the monarch is the embodiment of the reasonable.

The main theme is the conflict of personal and civic interests, feelings and duty

The highest dignity of a person is the fulfillment of duty, service to the state idea

Inheritance of antiquity as a model

(Oral explanation: the action was transferred to another time, not only in order to imitate antique samples, but also so that familiar life does not interfere with the viewer, reader to perceive ideas)

Imitation of "decorated" nature

Versailles - the residence of the French kings - was proud of its park, designed by Andre Le Nôtre. Nature took on rational, sometimes strictly geometric forms prescribed for her by the mind of man. The park was notable for the clear symmetry of alleys and ponds, strictly adjusted rows of trimmed trees and flower beds, and the solemn dignity of the statues located in it.

The Russian Petrodvorets is also a remarkable example of garden and park art. Although it was created almost a century later, it, like Versailles, embodied many of the strengths of classicism. The idea and execution of the project belongs to Andreas Schlüter and Bartholomew Rastrelli. First of all, this is the strict internal proportionality of the grandiose ensemble as a whole, which combines architectural structures, huge fountain cascades, sculptural groups and a strict layout of the park, striking in its spaciousness and purity of proportions.

Before you is the largest Peterhof fountain "Samson tearing the lion's mouth", created by sculptor Mikhail Kozlovsky.

Ø Why do you think this is a classic piece? (Ancient hero, his beauty, patriotic theme, glorification of the monarch)

The painters of classicism were no less than the architects, true to the principles of this direction.

Ø Find here the features of classicism

The theoretician of French classicism, Nicolas Boileau-Despreo, in his work “Poetic Art” outlined the principles of classicism in literature.

Basic requirements of classicism in literature

1. Heroes - “images without faces”. They do not change, being the spokesmen for common truths.

2. The use of the common language was excluded

3. Requirement of compositional rigor

4. Observance in the work of three unities: time, place and action.

5. Strict division into genres.

6. Role system

"High": tragedies, epic poems, odes, hymns

"Low": comedies, satires, fables

Mixing genres was considered unacceptable!

But the opinion of Moliere: "The task of comedy is to castigate vices."

3. Analytical work

Ø Let's remember what genre the classics considered comedy? (Low.)

Ø Why? (Low heroes, living life (“low”), everyday, low passions.)

Ø Is Fonvizin's work really a comedy? What is she making fun of?

Ø - What is the ideal of a man for the classicists? (A virtuous, law-abiding, enlightened, educated, educated citizen serving for the good of the Motherland.)

Ø Is there such a hero in Fonvizin's comedy? (Yes, this is Starodum, Pravdin)

Ø What ideas do they profess?

Ø Is there a unity of time in comedy?

Ø Is there unity of place?

Ø Is there unity of action? (No, there are two conflicts, two storylines)

Ø Is there a division into positive and negative characters?

Ø What does Fonvizin believe in as a writer of the Enlightenment? (The belief in reason that law and education can correct the mores of society is a direct expression of the author's ideal.)

Ø And what canons of classicism does the writer depart from?

Ø 1. A hero-scheme, a carrier of one quality (Fonvizin has individual traits, types). Examples? (For positive heroes, Fonvizin creates a biography, as, for example, with Starodum)

Ø 2. External comedy built on farcical scenes - comic scenes intertwined with the action, which form its basis, laughter has the power of negation. Examples?

Ø 3. The purity of the genre - a mixture of genres (satire and humor). Examples?

Ø 4. Images of goodies are features of really new people. Examples?

Ø 5. Conditionality of the place of action, fictional pictures of life - a specific place of action, true pictures of everyday life. Examples?

Ø 6. More conditional characters - the conditionality of characters by the environment, upbringing. Examples?

Let us now turn to the question of creating a comic

Answer. Fonvizin uses “talking” surnames, self-exposing phrases.

Question. These are traditional techniques for the comedy of classicism. Pay attention to the appearance of off-plot scenes, i.e. scenes not related to the plot, which was completely new in Russian dramaturgy. Name these scenes. What do you think it gave the author?

Answer. Extra-plot scenes are, for example, a scene with trying on a caftan, a conversation between Prostakova and her brother, with Eremeevna. They allowed the author to deepen the idea of an uncultured landowner family, the baseness of its requests and aspirations, the absence of high ideals, and the unreasonableness of such an intra-family structure. All this convinced the viewer of the plausibility and vitality of what was happening on stage.

Ø “Why do these scenes look with genuine interest?” (The characters of the negative heroes turned out to be more vital, deeper, more interesting.)

This happened for a number of reasons: the playwright tried to explain the characters' characters by the conditions of their life, upbringing.

Ø Prove this with examples from comedy.

The speech of negative characters sets off the individual characteristics of the characters, we have already noted this on the example of Prostakova's speech characteristics.

Ø Define another feature of the comedy "Undergrowth", starting from the words of Vyazemsky about Prostakova: "Her image stands on the boundary between tragedy and comedy."

Question. What is the most important feature noted by P. Vyazemsky?

Answer. The comedy combines the sad and the funny, the sublime and the mundane. And this was new for classicism.

Ø “What did you see the features of the comedy finale in?” (vice is punished, virtue triumphs. In fact, this did not happen, because the heroes did not embark on the path of virtue, which would be contrary to their moral essence.)

“ Of course, the comedy “Undergrowth” is a work of Russian classicism. But it is at the origins of Russian realistic literature. In Fonvizin's play, everything is Russian, national: theme, plot, conflict, characters. The great merit of Fonvizin is that, being within the framework of the classic rules and conventions, he managed to destroy many of them, creating a work deeply innovative both in content and in artistic form.

Ø Concluding our conversation, let's try to answer a few more questions: “Do you think that for our time, which is very difficult, imbued with a thirst for money, power, are ideas so dear to Fonvizin viable?

Ø Are the ideas of citizenship, service to the Fatherland, so beloved by the classicists, outdated today?

Homework:

1. Learn a lecture

- #1

Super! The children were delighted. This is the best thing on the internet. Thanks!!!

- #2

Thank you very much, I hand over literature, I decided to repeat the entire school curriculum from beginning to end, your videos are just the way! Briefly, clearly, understandably.

- #3

Foreword

A few years ago, in the club of critics of the Leningrad House of Cinema, they discussed the film by E. Motyl "The Star of Captivating Happiness." In the course of the conversation, the question arose about the degree of reliability with which people and events of the 1820s are recreated on the screen. Many said with irritation that again our actors were like mummers in these uniforms and ball gowns, that the “cavalry guards” had the manners of vocational school pupils, and the “secular ladies” were flirting like ice cream saleswomen, etc., until one historian asked who present would venture to appear in the aristocratic salon of the XIX century? The audience fell silent ... The historian recalled that K. S. Stanislavsky, who, as they say, was not brought up at the stable, preparing for the role of Arbenin in Lermontov’s Masquerade, went to A. A. Stakhovich, an aristocrat famous for his impeccable manners, to study subtleties of "good tone". Today, our artists have no one to go to for this purpose, and therefore there is nothing to ask them.

My supervisor, the well-known Pushkinist N. V. Izmailov, perfectly remembered pre-revolutionary Russian society. When a multi-part film was shown on television - a screen version of the novel by A. N. Tolstoy "Walking through the torments", I asked him how similar the characters of the film are to the officers of the tsarist army? “They are not at all similar,” Nikolai Vasilyevich said firmly. “Those were the most intelligent people, and these ... Faces, manners ... ”I remarked conciliatoryly that, after all, the actresses playing Dasha and Katya are very beautiful. The old man shrugged indifferently: "Pretty grisettes ..."

Of course, the actors are not to blame: they cannot play people they have never seen.

The Russian aristocrat of the 19th century is a very special type of personality. The whole style of his life, demeanor, even appearance - bore the imprint of a certain cultural tradition. That is why it is so difficult for a modern person to “depict” him: imitation of only external features of behavior looks unbearably false. (Probably, those merchants who imitated the exceptionally beautiful surroundings of noble life, while remaining indifferent to the spiritual values of noble culture, looked something like this.)

On the other hand, focusing only on spiritual values, one can lose sight of how they were implemented in the practice of everyday life. The so-called bon ton [Good tone (French)] consisted in the organic unity of ethical and etiquette norms. Therefore, in order to imagine a Russian nobleman in his living form, it is necessary to see the connection between the rules of conduct and the ethical attitudes adopted in his circle.

The nobility stood out among other classes of Russian society for its distinct, pronounced orientation towards a certain speculative ideal. In the second half of the 18th century, the noble elite, dreaming of the leadership of their class in the political, social and cultural life of Russia, rightly saw the main obstacle to achieving this goal in the depressingly low cultural level of the overwhelming majority of Russian landowners. (An exhaustive idea of it is given by the famous comedy of D. I. Fonvizin “Undergrowth”.) But, not embarrassed by the exorbitant difficulty of the task, the ideologists and spiritual leaders of the nobility undertook to raise enlightened and virtuous citizens, noble knights and courteous gentlemen from the children of the Prostakovs and Skotinins. This goal is manifested to varying degrees in various spheres of noble culture from literature to everyday life. Of particular importance in this regard, of course, was the upbringing of children.

The so-called “normative education” was applied to noble children, that is, education aimed not so much at revealing the individuality of the child, but rather at polishing his personality according to a certain model.

From the standpoint of modern pedagogy, the shortcomings of such education are obvious. At the same time, it is impossible not to notice that sometimes it brought amazing results. In the last century in Russia there were people who amaze us today with their almost unbelievable honesty, nobility and subtlety of feelings. Literary descriptions, portraits of painters convey their special, forgotten charm, which we are no longer able to imitate. They grew up like this not only thanks to outstanding personal qualities, but also thanks to a special upbringing. Here we will try to describe the ideal, towards which the noble child was oriented, and to demonstrate the methods and techniques with which the educators sought to develop the necessary qualities in the ward.

At the same time, it must be borne in mind that “noble education” is not a pedagogical system, not a special methodology, not even a set of rules. This is, first of all, a way of life, a style of behavior, assimilated partly consciously, partly unconsciously: through habit and imitation; this is a tradition that is not discussed, but observed. Therefore, it is not so much theoretical prescriptions that are important as those principles that actually manifested themselves in everyday life, behavior, and live communication. Consequently, it is more useful to turn not to textbooks of good taste, but to memoirs, letters, diaries, fiction. Numerous examples from the life of English and French high society are justified and even necessary, because the Russian nobility of the Petrine and post-Petrine era was consciously oriented towards the Western model of behavior and sought to assimilate European norms of life and etiquette.

The concept of "noble type of behavior", of course, is extremely arbitrary; like any generalized image, the image of a “Russian nobleman” cannot contain all the diversity of human individualities. However, it is possible to select from all this diversity the most characteristic and historically significant features.

In the words of Pushkin, each estate had its own “vices and weaknesses”, of course, the Russian nobility also had them, there is no need to idealize it. But more than enough has been said about the "vices" in previous decades, today it is worth recalling the good things that were in the Russian nobility. In the customs of the nobility and the upbringing of the nobility, much is inextricably linked with the life of a bygone era; certain losses would in any case be natural and inevitable. But there are losses that might not be. Now this is becoming more and more obvious, and therefore some forgotten traditions are beginning to be timidly revived. In order to, as far as possible, help their revival, this book is written.

"SEME REAL MEMORIES

the nobility should be the historical memories of the people."

A. S. Pushkin. A novel in letters.

Introduction

The noticeable interest of modern society in the noble life of the last century sometimes causes ironic remarks, the meaning of which boils down to the fact that the vast majority of today's zealots of noble customs are descendants of not princes and counts at all, but serfs. The position is not only tactless, but also stupid: Pushkin's poems and Turgenev's novels were read by a very narrow circle of people, which then exhausted educated Russia, but the great Russian writers knew that they were writing not only for them, but also for the grandchildren of those who are "now wild". The same can be said about the moral norms worked out by the privileged class. Pushkin reasoned: “What does the nobility learn? Independence, courage, nobility (honor in general). Are not these qualities natural? So; but the way of life can develop them, strengthen them - or stifle them. Do they need the people, as well as, for example, diligence? They are needed, because they are the sauve garde [Protection (French)] of the industrious class, which has no time to develop these qualities. The well-known lawyer, historian and public figure K. D. Kavelin believed that the generation of people of the Alexander era "will always serve as a vivid example of what kind of people can be developed in Russia under favorable circumstances." It can be said that those qualities of a Russian person developed and improved in the nobility, which, ideally, should eventually penetrate into the environment where so far "there was no time to develop them."

The experience of European countries, the hope for the success of education and civilization in Russia, and finally, simple sympathy for the disadvantaged compatriots - everything fed the belief that in the future the inequality of the strata of Russian society would gradually smooth out, and the nobility in its entirety (from works to good manners) will become the property of all estates, will be the common legal legacy of the free and enlightened citizens of Russia in the 20th century... Unfortunately, Russian history has taken a completely different, tragic and bloody path; natural cultural evolution has been interrupted, and now one can only guess what its results would have been. Life, style of relationships, unwritten rules of behavior - turned out to be perhaps the most fragile material; it could not be hidden in museums and libraries, and it turned out to be impossible to preserve it in the practice of real life. Attempts to regain what was lost by teaching "good manners" cannot bring the desired result. In “The Tale of Sonechka” by Tsvetaeva, a young actor reflects on the lessons of “good manners” that A. A. Stakhovich gave to the accounts of the theater studio: “For me, his bow and bonton is not an answer, but a question, a question of the present - to the past, my question is - topic, and I'm trying to answer it myself. (...) These bows were given to Stakhovich when he was born, it was a gift from his ancestors - to him in the cradle. I came into the world - naked, but although naked, I should not senselessly dress in someone else's, at least a beautiful dress.

In order for this “beautiful dress” – attractive external features of the life and appearance of the nobility – to become, if not one’s own, but at least understandable and familiar, it is necessary to imagine both the ethical meaning of etiquette norms and the historical context in which these norms were formed.

Let us try, if not to restore, then to recall some of the features of the disappeared society.

"IL N" Y A QU "UNE SEULE BONNE

societe c "est la bonne".

"There is no other good society than

good."

A. S. Pushkin. From conversation.

Once, wanting to prick an interlocutor who was proud of his closeness to high-ranking persons, Pushkin told an expressive episode. He was at N.M. Karamzin’s, but he could not really talk to him, since guests came to the historiographer, one after another. As luck would have it, these visitors were all senators. Seeing the latter off, Karamzin said to Pushkin: “Avez-vous remarque, mon cher ami, que parmit tous ces messieurs li n” y avait pas un seul qui soit un homme de bonne companie? [Did you notice, my dear friend, that of all these gentlemen, no one belongs to good society? (French)]

This clarification is extremely important for us, because those personal qualities and norms of behavior that we will discuss were characteristic of a “good”, and not generally a noble or so-called secular society. Another thing is that in those historical circumstances, "good society" was made up almost exclusively of the nobility. It must be admitted that there were not so many truly educated people (in the understanding of Pushkin and Karamzin) even then. Not without reason, making an entry in his diary about the death of Prince Kochubey, Pushkin remarks: "... he was a well-mannered man - and this is rare with us, and thanks for that." When the memoirist M. I. Zhikharev uses the expression “stinking majority”, he does not mean smerds, not serfs, who, for obvious reasons, did not take any part in public life at all, but most people of their circle, including “ magnificent ladies and people in blue and other different colors of ribbons with high ranks and big names. At the same time, as K. D. Kavelin recalled, “Talents that came out of the people, even from serfs, even people who gave only hope of becoming later writers, scientists, artists, whoever they were, were received cordially and friendly, were introduced into circles and families on an equal footing with everyone. It was not a comedy played out in front of strangers, but a real, sincere truth - the result of a deep conviction, which turned into habits and mores, that education, talent, scientists and literary merits are higher than class privileges, wealth and nobility. If these words seem to be an exaggeration to someone, then here is the testimony of Count V. A. Sollogub, an aristocrat and courtier who spent his whole life in high society. “There is nothing more absurd and false than the conviction of the tribal swagger of the Russian aristocracy,” he argued and cited as an example Prince V.F. Odoevsky, a representative of the oldest noble family in Russia, who was an extremely modest man who mentioned his aristocratic origin in no other way like a joke. “Nevertheless,” writes Sollogub, “he was a true aristocrat, because he lived only for science, for art, for the good and for friends, that is, for all decent and intelligent people he met.”

Paraphrasing Rossini's statement that there are only two kinds of music - good and bad, Sollogub said that in Russia "there are also only two kinds of people - educated and uneducated." Without forgetting that the concept of “education” was then given a very broad meaning, we note that the values that were cultivated by the “enlightened minority” may turn out to be useful today. As Pushkin (who had the opportunity to observe and compare) stated: “A good society can exist not in the highest circle, but wherever there are honest, intelligent and educated people.”

"Slu LIVE FAITHFULLY TO WHOM YOU WILL swear.”

A. S. Pushkin. Captain's daughter.

The attitude of the nobleman was largely determined by the position and role of the nobility as a whole in the state. In Russia XVIII - the first half of the XIX century. the nobility was a privileged and serving class at the same time, and this gave rise in the nobleman's soul to a peculiar combination of a sense of being chosen and a sense of responsibility. The attitude to military and public service was associated in the understanding of the nobleman with the service to society, Russia. When Chatsky from A. S. Griboedov’s comedy “Woe from Wit” defiantly declares: “I would be glad to serve, it’s sickening to serve,” he means that in reality, service to the Fatherland was often replaced by service to “persons”, nobles and high-ranking officials. But we note that even the independent and self-willed Chatsky, in principle, does not oppose the service, but is only indignant at the fact that this noble cause is discredited by selfish and narrow-minded people.

Despite the fact that public service was often opposed to the private activities of independent people (a similar position was defended in one form or another by Novikov, Derzhavin, Karamzin), there was no deep contradiction here. Firstly, the disagreements concerned, in essence, in what field it was possible to bring more benefit to the Fatherland; the very desire to benefit him was not questioned. Secondly, even a nobleman who was not in the public service was not in the full sense of the word a private person: he was forced to deal with the affairs of his estate and his peasants. One of Pushkin's heroes remarked on this: “The title of a landowner is the same service. To manage three thousand souls whose well-being depends is completely more courageous than to command a platoon or write diplomatic dispatches. Of course, not every landowner was so clearly aware of his civic duty, but compliance with these ideals was perceived as unworthy behavior, deserving public censure, which was instilled in noble children from childhood. The rule "to serve faithfully" was included in the code of noble honor and, thus, had the status of an ethical value, a moral law. This law was recognized for many decades by people belonging to different circles of noble society. Let us pay attention to the fact that such different people as the poor landowner Andrei Petrovich Grinev, who does not read anything but the Court Calendar, and the European-educated aristocrat Prince Nikolai Andreevich Bolkonsky, escorting their sons to the army, give them, in general, similar parting words.

“The father said to me: Farewell, Peter. Serve faithfully to whom you swear; obey the bosses; do not chase after their affection; do not ask for service; do not excuse yourself from the service; and remember the proverb: take care of the dress again, and honor from youth. (A. S. Pushkin. Captain's daughter.)

“Kiss here,” he (the old prince - O. M.) showed his cheek, “thank you, thank you!

- What do you thank me for?

- Because you don’t overstay, you don’t hold on to a woman’s skirt. Service first. Thank you, thank you! (...)

- Now listen: give the letter to Mikhail Ilarionovich. I am writing that he will use you in good places and not keep you as an adjutant for a long time: a bad position! (...) Yes, write how he will accept you. If it's good, serve. Nikolai Andreevich Bolkonsky, the son, out of mercy, will not serve anyone. (L. N. Tolstoy. War and Peace.)

The nobility's sense of duty was mixed with self-esteem, and service to the Fatherland was not only a duty, but also a right. In this regard, one scene from the novel "War and Peace" is very indicative, where Andrei is furious at various jokes by Zherkov about the general - commander of the Allied army, which has just suffered a crushing defeat.

“Yes, you understand that we are either officers who serve our tsar and fatherland and rejoice in our common success and grieve over our common failure, or we are lackeys who do not care about the master’s business.”

The difference between the service of the nobility and the service of the lackey is seen in the fact that the former presupposes a personal and lively interest in matters of national importance. The nobleman serves the king as a vassal to the overlord, but does a common thing with him, bearing his share of responsibility for everything that happens in the state.

When a little boy’s playful question “And when will I be king?”, the mother seriously answers: “You will not be king, but if you want, you can help the Tsar,” she imperceptibly inspires her son with one of the basic principles of noble ethics. (N. G. Garin-Mikhailovsky. Childhood of the Theme.) The nobles' opposition, basically, was upholding their right to "help the tsar", upholding their legitimate, natural right to participate in government.

Griboedov's well-known phrase from a letter to S. Begichev: "... and you, I hope, like any honest person these days, serve from rank, and not from honor" - is, of course, defiantly defiant, shocking in nature. This position was popular among the youth of the 1810s, in whom a sharp dissatisfaction with the state structure of Russia gave rise to the conviction that it was a duty of honor not to serve such a state, but to strive to remake it. It was these sentiments that largely predetermined the Decembrist movement. However, they did not become a characteristic feature of the noble worldview in general. Let us note that Griboyedov himself, as is well known, did not renounce an important government post in his time and died while doing his duty.

It must be emphasized that a zealous attitude to the service had nothing to do with loyalty or careerism. An expressive example in this regard was Admiral Nikolai Semenovich Mordvinov. The admiral was famous for his courage and independence of judgment and actions; he was the only member of the commission of inquiry in the case of the Decembrists who opposed the death sentence. Pushkin wrote that Mordvinov “contains the Russian opposition alone,” and K. Ryleev dedicated the ode “Civil Courage” to him. Mordvinov more than once fell into disgrace, but when he did not refuse an offer to take this or that public post, he said that “every honest person should not shirk the duty that the Supreme Power or the choice of citizens imposes on him.”

Until the last years of the existence of Tsarist Russia, when, in the words of Alexander Blok, “the most honest of the tsar’s servants had already signed up as liberals,” the nobility was resolutely uncharacteristic of that emphasized negative, squeamish attitude to public service, which all generations flaunted to one degree or another. oppositional Russian intelligentsia.

"I'M IN WHAT I CAN OFFEND

demolish,

But I will not endure it, which it endures

honour."

A. P. Sumarokov. On the love of virtue.

"...in all the splendor of his madness."

A. S. Pushkin. From journalism.

One of the principles of the noble ideology was the conviction that the high position of a nobleman in society obliges him to be a model of high moral qualities. The rational scheme of the hierarchy of social and moral values, which substantiated such a belief, remained relevant in the 18th century, then it was replaced by more complex concepts of the social structure, and the postulate of the moral height of a nobleman gradually transformed into a purely ethical requirement: “To whom much is given, much and ask." (The Grand Duke Konstantin (poet K. R.) did not tire of repeating these words to his sons already at the beginning of the 20th century.)

Obviously, children were brought up in this spirit in many noble families. Let us recall an episode from Garin-Mikhailovsky's story "The Childhood of Theme": Theme threw a stone at the butcher, who saved the boy from an angry bull, and then kicked his ears so that he would not climb where it was not necessary. Tema's mother was very angry: “Why are you giving free rein to your hands, you worthless boy? The butcher is rude, but a kind man, and you are rude and evil! .. Go, I don't want such a son!

Theme came and left again, until at last everything was somehow illuminated by itself: his role in this matter, and his guilt, and the butcher's unconscious rudeness, and Theme's responsibility for the created state of affairs.

“You, you will always be to blame, because nothing has been given to them, but it has been given to you; and ask you."

We emphasize that the decisive setting in the upbringing of a noble child was that he was oriented not to success, but to an ideal. He should have been brave, honest, educated, not for anything (fame, wealth, rank), but because he is a nobleman, that he has been given a lot, because he is just like that. (Sharp criticism of the nobility by noble writers - “other, Pushkin, etc. - is usually directed at those nobles who do not correspond to this ideal, do not fulfill their destiny.)

Noble honor, point d "honneur, was considered almost the main class virtue. According to noble ethics, "honor" does not give a person any privileges, but, on the contrary, makes him more vulnerable than others. Ideally, honor was the basic law of a nobleman's behavior, of course unconditionally prevailing over any other considerations, be it profit, success, security, or just prudence.The boundary between honor and dishonor was sometimes purely verbal, Pushkin even defined honor as "the willingness to sacrifice everything to maintain" some conditional rule. In another place, he wrote: "Secular people have their own way of thinking, their own prejudices, incomprehensible to another caste. How will you explain to a peaceful Aleut a duel between two French officers? Their ticklishness will seem extremely strange to him, and he will almost be right."

Not only from the point of view of the “peaceful Aleut”, but also from the standpoint of common sense, the duel was pure madness, because the price that the offender had to pay was too high. Moreover, rather vain considerations often pushed the nobleman to a duel: fear of condemnation, an eye on "public opinion", which Pushkin called "the spring of honor."

If in such a duel a person happened to kill his opponent, for whom he had, in fact, no evil feelings, the unwitting killer experienced a severe shock. A textbook example of such a situation is the duel between Vladimir Lensky and Eugene Onegin.

Nevertheless, this "madness" certainly had its own "brilliance": the willingness to risk one's life in order not to become dishonored required considerable courage, as well as honesty both to others and to oneself. A person had to get used to being responsible for his words; "offend and not to fight” (in the words of Pushkin) – was considered the limit of baseness. This also dictated a certain style of behavior: it was necessary to avoid both excessive suspiciousness and insufficient exactingness. Chesterfield in his "Letters to his son" gives the young man clear recommendations on this matter: "Remember that for a gentleman and a man of talent there are only two procedes [Modes of action (French)]: either be emphatically polite to your enemy, or knock him off legs. If a person deliberately and deliberately insults and rudely humiliates you, hit him, but if he only hurts you, the best way to get revenge is to be exquisitely polite to him outwardly and at the same time counteract him and return his barbs, maybe even with interest. ." Chesterfield explains to his son why it is necessary to control oneself so as to be friendly and courteous, even with someone who definitely does not love you and is trying to harm you: if by your behavior you let others feel that you are hurt and offended, you will be obliged to properly repay for the offense . But to demand satisfaction for every sideways glance is to put oneself in a ridiculous position.

So, showing offense and not doing anything to straighten up the offender or just sort things out with him was considered a sign of bad upbringing and dubious moral principles. “Decent people,” Chesterfield argued, “never pout at each other.”

The art of communication for a person sensitive to matters of honor consisted, in particular, in avoiding situations fraught with the possibility of falling into a vulnerable position. Ironic phrase of Karamzin:

"Il ne faut pas qu" un honnete homme merite d "etre pendu." ["An honest man should not subject himself to the gallows" (French)] has not only a political, but also a moral aspect. When, in Garin-Mikhailovsky's story, the mother reprimands her son for throwing a stone at the butcher, the boy justifies himself by saying that the butcher could have taken him out by the hand, and not by the ear! But the mother retorts: “Why do you put yourself in such a position that they can take you by the ear?” The parallel between Karamzin's subtle maxim and moralizing for Theme looks like; frivolously, but at the heart of these arguments so far from each other lies a worldview that is close in type.

The ever-present threat of a deadly duel greatly increased the price of words and, in particular, the “word of honor”. A public insult inevitably led to a duel, but a public apology ended the conflict. To break this word meant ruining one's reputation once and for all, so a guarantee on parole was absolutely reliable. There are cases when a person, admitting his irreparable guilt, gave his word of honor to shoot himself - and kept his promise. In this atmosphere of increased exactingness and - at the same time - emphasized trust, noble children were also brought up.

P. K. Martyanov in his book “The Affairs and People of the Century” says that Admiral I. F. Kruzenshtern, director of the naval corps in the early 1840s, forgave the pupil any sin if he confessed. Once a cadet confessed to a really serious offense, and his battalion commander insisted on punishment. But Kruzenshtern was inexorable: “I gave my word that there would be no punishment, and I will keep my word! I will report to my sovereign that I have given my word! Let him charge me! And you leave, I beg you!”

Ekaterina Meshcherskaya tells a typical case in her memoirs. (Recall that she describes the life of aristocrats in the 10s of the 20th century.) Little Katya, for some reason disliked Prince Nikolai Barclay de Tolly, a handsome man and ladies' idol, composed a very offensive rhyme for him and imperceptibly slipped a piece of paper with her work into a dining room napkin prince's instrument. Suspicion fell on Prince Gorchakov, and the duel smelled in the air. Fortunately, Katya's elder brother recognized his sister's handwriting and brought her to the officer's room to explain herself. When the girl told everything, the officers burst out laughing, and only Gorchakov was silent and remained serious. “Child,” he said, looking at me sternly, “you do not even suspect how important your words are to me. The question is about the honor of the uniform... Do you understand?! I ask you to give me now, here, in front of everyone, your word of honor, that none of the adults, you understand, no one, and, most importantly, of the officers present here, did not help you write these poems. Katya solemnly gave her word of honor, and the conflict ended in general fun. The word of honor of the child was enough for the adult men, already ready for a duel, to completely calm down.

The duel, as a way of protecting honor, also carried a special function: it asserted a certain noble equality, independent of the bureaucratic and court hierarchy. A classic example of this kind: the proposal of Grand Duke Mikhail Pavlovich to bring satisfaction to any of the Semenov officers, as soon as they consider that he offended the honor of their regiment. The future Decembrist Mikhail Lunin then expressed his readiness to shoot with the emperor's brother. A less well-known, but similar, in essence, case, which P. K. Martyanov reports in his memoirs, occurred already in the 1840s.

One of the battalion commanders of the naval corps, Baron A. A. de Riedel, heard one of the senior midshipmen curse at the authorities for not allowing class before a certain hour. Since this order came precisely from Riedel, the baron considered himself insulted and told the pupil that he would not punish him and complain to his superiors, he would not go, but he demanded satisfaction for insulting his honor. The pupil resolutely denied that he meant to offend Riedel personally, but at the same time he did not fail to thank the commander for the honor he had done him with his challenge.

In both cases, the duel did not take place; the actions of both Lunin and Riedel were already perceived by contemporaries as extravagant; but nevertheless, the very possibility of such situations testifies to the existence of a certain norm of behavior, with which people in one way or another relate their actions.

Recall that the duel was officially banned and punishable; according to a well-known paradox, an officer could be expelled from the regiment "for a duel or for refusal." In the first case, he was put on trial and punished, in the second, the officers of the regiment suggested that he resign. Thus, the observance of the norms of noble ethics came into conflict with state institutions and entailed all sorts of troubles. This regularity made itself felt not only in the case of a duel.

A noble child, who was inculcated in the family with traditional ethical norms, experienced a shock when faced with the impossibility of following them in the conditions of a state educational institution, where he usually received his first experience of an independent life.

In Garin-Mikhailovsky's story, Tema's father, escorting his son to the first grade of the gymnasium, once again tells him about how shameful it is to tell tales, about the holy bonds of camaraderie and loyalty to friendship. "Theme listened to familiar stories and felt that he would be a reliable guardian of comradely honor." The test awaited him on the very first day: one of his classmates deliberately “set up” Theme and brought the wrath of his superiors on him. “He realized that he had become a victim of Vakhnov, he realized that it was necessary to explain himself, but to his misfortune, he also remembered his father’s instruction on partnership. It seemed especially convenient to him right now, in front of the whole class, to declare himself, so to speak, at once, and he spoke in an excited, but confident and convinced voice:

- Of course, I will never betray my comrades, but I can still say that I am not to blame for anything, because I was deceived very badly and sleep ...

– Shut up! roared a gentleman in a uniform tailcoat with a good obscenity.

"Bad boy!" As a result of this incident, the boy was almost expelled from the gymnasium. Neither the arguments of his father, General Kartashev, about the benefits of "partnership", nor the ardent pleas of his mother to reckon with the pride of the child, made an impression on the director of the gymnasium.

He categorically told Tema's distressed and agitated parents that their son should not obey family rules, but "general" ones, if he wants to "make a successful career."

Needless to say, he was absolutely right about this. Loyalty to the code of noble honor did not in any way favor a successful career either during the apotheosis of the autocratic bureaucratic state of the 1830s and 40s, or during the democratic reforms of the 1860s and 70s. P. K. Martyanov recalls how one old general explained what prevented him from taking part in the activities of elected authorities or commercial institutions: “... we were brought up in the Cadet rules -“ honor comes first. Is this available to the kulak? Will he understand that honor is the stimulus of all life? He only needs money, and how to get it is indifferent - just to get it. Where can there be a point of contact between us?”

If the "stimulus of all life" is honor, it is quite obvious that the guideline in human behavior is not results, but principles. Leo Tolstoy's son Sergei claimed that his father's motto was a French proverb: "Fais ce que dois, advienne que pourra." actions should not be guided by their intended consequences. As you know, Leo Tolstoy put his own meaning into the concept of duty, sometimes unexpected for society. But the very attitude: to think about the ethical significance of an act, and not about its practical consequences, is traditional for the noble code of honor. Education based on such principles seems completely reckless: not only does it not equip a person with the qualities necessary for success, but it declares these qualities to be shameful. However, much depends on how you understand success in life. If this concept includes not only external well-being, but also the internal state of a person - a clear conscience, high self-esteem, and so on, then noble education is not as impractical as it seems. More recently, we had the opportunity to see old people from noble families, whose life, by all worldly standards, developed catastrophically unsuccessfully under the Soviet regime. Meanwhile, in their behavior there were no signs of either hysteria or anger. Maybe aristocratic pride did not allow them to show such feelings, or maybe they were really supported by the conviction that they lived the way they should?

Protecting one's honor, human dignity has always been a difficult task in the Russian state, traditionally indifferent to the personal rights of its subjects, even if they belong to the "noble" class. Noble ethics, paradoxically, carried a democratic charge: it demanded, even if only within one class, respect for the rights of the individual, regardless of the official hierarchy. True, following this requirement for subordinates was risky.

N. A. Tuchkova-Ogareva cites in her memoirs an incident that happened to her father, then a very young officer, Alexei Tuchkov. He “was standing on the porch of the station house when a wagon drove up in which the general was sitting (later they learned that it was General Neidgart.) He began to call my father with his finger.

- Hey, you, come here! shouted the general.

“Come yourself if you need to,” answered the father, not moving from his place.

"However, who are you?" the general asks angrily.

“An officer sent on official duty,” his father answered him.

"Don't you see who I am?" cried the general.

- I see, - answered the father, - a man of bad education.

How dare you speak so boldly? Your name? the general fumed.

- Lieutenant Tuchkov of the General Staff, so that you do not think that I am hiding, - answered the father.

This unpleasant story could have ended very badly, but fortunately, Neidgardt was well acquainted with the old Tuchkovs, and therefore kept silent, almost because he himself was to blame.

In the novel "War and Peace" a scene close in spirit is described.

“How are you standing? Where is the leg? Where is the leg? - shouted the regimental commander with an expression of suffering in his voice, another five people did not reach Dolokhov, dressed in a bluish overcoat.

Dolokhov slowly straightened his bent leg and straight, with his bright and insolent look, looked into the general's face.

Why the blue overcoat? Down with! .. Sergeant major! Change his clothes ... rubbish ...

He didn't get to finish.

“General, I am obliged to carry out orders, but I am not obliged to endure ...” Dolokhov said hastily.

- Do not talk in the front! .. Do not talk, do not talk! ..

“I am not obliged to endure insults,” Dolokhov finished loudly, sonorously.

The eyes of the general and the soldier met. The General fell silent, angrily pulling down his tight scarf.

“If you please, change your clothes, please,” he said as he walked away.

These principles of behavior were assimilated by a nobleman from childhood, although it was even more difficult for a child to defend them. The already mentioned scene from the story by Garin-Mikhailovsky, where Theme is explained to the enraged director of the gymnasium, ended as follows:

“To the subject, not accustomed to gymnasium discipline, another unfortunate thought came into his head.

“Let me…” he spoke in a trembling, bewildered voice. “Do you dare to yell at me like that and scold me?

- Won!! roared the gentleman in the evening dress, and, grabbing Tema by the arm, dragged him along the corridor.

Let us pay attention to the fact that both the reckless duelist Dolokhov and the little schoolboy Tem are talking about the same thing: do not dare to offend! This conviction, brought up from an early age, was constantly present in the mind of a nobleman, determining his reactions and actions. Scrupulously guarding his honor, the nobleman, of course, took into account purely conventional, etiquette norms of behavior. But the main thing is that he defended his human dignity.

A heightened sense of self-worth was brought up and developed in the child by a whole system of different, outwardly sometimes unrelated demands.

"... AND I SURE THAT HE SHOULD BE

me in physical cowardice,

he would have cursed me."

V. Nabokov. Gift.

The nature of the relationship between father and son, the importance that they attach to physical courage, so expressively conveyed by one phrase of Nabokov's hero, is very indicative of the noble environment.

Pushkin noted in his notes (“Table-Talk”) one of Prince Potemkin’s instructions to his nephew N.N. if not, then strengthen your innate courage by frequent dealing with the enemy. Alexander Griboyedov hardly knew about these recommendations of Potemkin, but he himself acted in a similar way, which indicates the persistence of such behavioral stereotypes. Ks. Polevoy recalled: “Of course,” Griboedov remarked among other things, “if I wanted my nose to be shorter or longer, it would be stupid because it’s impossible. But in the moral sense, which is sometimes deceptively physical for the senses, one can make everything out of oneself. I say this because I have experienced many things with myself. For example, in the last Persian campaign, during one battle, I happened to be with Prince Suvorov. The nucleus from the enemy battery hit near the prince, showered him with earth, and at first I thought that he had been killed. This filled me with such a shudder that I trembled. The prince was only shell-shocked, but I felt an involuntary trembling and could not drive away the disgusting feeling of timidity. This offended me terribly. So I'm a coward at heart? The thought is unbearable for a decent person, and I decided, at whatever cost, to cure myself of timidity, which, perhaps, ascribe to the physical composition, organism, innate feeling. But I wanted not to tremble in front of the cannonballs, in view of death, and on occasion I stood in a place where shots were taken from an enemy battery. There I counted the number of shots that I myself had appointed, and then, quietly turning my horse, calmly rode away. Do you know that it drove away my timidity? After that, I was not shy from any military danger. But succumb to the feeling of fear, it will intensify and assert itself.

Noteworthy is the importance attached to courage, and the confidence that it can be brought up, developed through strong-willed efforts and training. It is noteworthy that this conversation does not take place at the bivouac, but in the salon of Prince V.F. Odoevsky, in the company of writers. Regardless of the type of activity, courage was considered the unconditional dignity of a nobleman, and this was taken into account when raising a child.

Comparing "Childhood" by L. N. Tolstoy and "Childhood of Nikita" by A. N. Tolstoy, we see that some customs remained unchanged in noble families for decades. For example, a boy of 10 - 12 years old had to ride on an equal footing with adults. Although in the works mentioned above, mothers cry and ask fathers to take care of their son, their protests look like a ritual that accompanies this mandatory test for a boy. There really was a certain danger to the child here; the eldest son of Nicholas I, Alexander, at about that age, fell off his horse and crashed so badly that he lay in bed for several days. This case did not have any consequences in the sense of striving to avoid such a risk in the future; having recovered, the heir to the throne continued training.

The future famous artist M. V. Dobuzhinsky, like others, was put on a horse by his father when he was 10 years old. For the first time, Dobuzhinsky recalled, “for me, he chose a tall white horse, seemingly meek and of respectable age, but nevertheless took it as a precaution on a pole [Chumbur is a long belt tied to a bridle.]. We drove the whole longest boulevard and just turned back, varnish my old horse suddenly rushed off at full speed march-march, and out of surprise my father missed his twig. No matter how he whipped his Cossack pacer, my horse flew like a whirlwind, and my father could not catch up with me, he only shouted after me: "Hold on tight." We raced along the whole boulevard, full of people, the ladies gasped and screamed - my horse turned straight into the stable yard and rushed to the door of his stable. Then I suddenly, like lightning, remembered one funny drawing from the Uber Land und Meeg magazine, where the gentleman was depicted in the same position, as he slams his head against the door frame and a top hat flies from him, and I crouched down on the saddle as low as possible and saved himself - the jamb cut off my hat, which fell on the horse's croup. A few seconds later, my father galloped into the yard and saw me as if nothing had happened, sitting on a horse in a stall. He kissed me hard, his "fellow", who passed a really terrible exam. The yard was filled with compassionate Ladies and, to their general admiration and fear, we again went for a walk, this time the pole was tightly tied, and the walk went smoothly and successfully.

Note, by the way, the mention of "ladies": to look worthy in their eyes was, of course, important for a ten-year-old boy.

In the memoirs of Mikhail Bestuzhev, characteristic episodes from his childhood have come down to us.

One day, several boys went boating around Krestovsky Island, and suddenly the boat hit an underwater pile, broke through, and began to sink. Everyone was terribly frightened and “thought to seek salvation in desperate cries, which were completely drowned out by the piercing cry of little brother Petrusha. Only our ataman Rinaldo was not lost. (Alexander Bestuzhev, future writer Bestuzhev-Marlinsky - Oh, M.) He took off his jacket and hastily plugged the hole; then he grabbed Brother Peter and, lifting him above the water, shouted: “Coward! If you don't stop screaming, I'll throw you into the water!" Although I was also scared, I did not dare to scream. The only adult in the boat, Herr Schmidt, was completely at a loss and waved the oars randomly through the air. Brother Alexander snatched the oar from him, sat down himself and told me to take another. We soon hit the shore."

Attention is drawn not only to the rare self-control and determination shown by the boy, but also to very severe educational measures in relation to his younger brothers. Another time, during a game of robbers, Mikhail did not hear the retreat signal, “and when it was repeated, the raft had already set sail, so that when I ran to the shore, I stopped in indecision.

"Jump if you don't want to be captured," shouted Rinaldo Rinaldini.

With an extraordinary effort, I made a salto mortale... Falling onto the raft, I slipped on the wet boards, hit the back of my head hard - I lost my senses. What happened next, I don't remember. When I woke up, I saw myself on the shoulders of my brother, exhausted from fatigue; he still had enough strength to bring me to the river, refresh and wash my head of blood.

- Well, Michel, - he said, caressing me, - I'm glad that you woke up, otherwise we would have frightened my mother and sisters. You were badly hurt, I am to blame for this, but you did not fall into the hands of the sbirs, because it would be a shame, but now, on the contrary, you behaved perfectly. Brothers! I am proud of him and make him my assistant,” he concluded, turning to the robbers who surrounded us.

Alexander Bestuzhev, although he had a markedly domineering character, was not at all a tyrant for his brothers. The same demands were placed on him. Once, the eldest of the Bestuzhev brothers, Nikolai, who had already served as a naval officer, took Alexander to his frigate during the summer holidays. At first, Nikolai forbade his teenage brother “to climb the masts and participate in the sailor’s work usually performed by midshipmen,” but one day, he recalled, “Alexander entered my cabin and urged me to let him go home. To my question about the reason, he said: “Brother, your prohibitions have made me the laughingstock of the entire frigate: they call me an underground mole, a mountain rat [Nikolai was teased like that because he studied in a mountain corps.] and God knows what, almost a coward . Either you let me live on an equal footing with everyone, or let me go home. He was right, and I reluctantly lifted the ban. In the morning he already appeared in a sailor's shirt, wide canvas trousers, with a cap on one side (...) and in order to prove in practice that he was not a crow in peacock feathers, he threw himself into the sailor's whirlpool, headlong. Sometimes my heart sank when, out of youth, he ran without holding on to the yardarm to fasten the bayonet-bolt, or descended headfirst along one rope from the very top of the mast, or, riding a boat in a strong wind, carried such sails that drew water on board. (...) He achieved his goal: he earned affection and respect ... "

The episode from the memoirs of E. Meshcherskaya is sustained in the same spirit, although almost a hundred years have passed between the events described.

The girl's elder brother Vyacheslav considered it his duty to educate her. Knowing that his sister was afraid of thunderstorms, he dragged her by force onto the sill of the open window and set her under the downpour. Katya lost consciousness from fear, and when she came to herself, her brother wiped her wet face with his handkerchief and said: “Well, answer me: will you still be a coward and be afraid of a thunderstorm?” Then, carrying the girl in his arms down the stairs, he said: “And you, if you want me to love you and consider you my sister, be brave. Remember: there is no vice more shameful than cowardice.

The riskiness of such educational procedures was largely due to a sincere belief in their beneficence. Such methods were suitable, one must think, not for every child, but this belief, perhaps, made a corresponding impression on the children: they perceived such experiments on themselves not as the arbitrariness and cruelty of the elders, but as a necessary tempering of character. So E. Meshcherskaya, already an old woman, recalls this incident from her childhood without resentment and indignation; on the contrary, she concludes with satisfaction: "And I was never afraid of thunderstorms again."

"...UPA L ON ICE NOT WITH A HORSE,

but with a horse: big difference for

my equestrian vanity."

A. S. Pushkin. From a letter to P. A. Vyazemsky.

Courage and stamina, which were certainly required of a nobleman, were almost impossible without appropriate physical strength and dexterity. It is not surprising that these qualities were highly valued and diligently instilled in children. At the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum, where Pushkin studied, time was allotted every day for "gymnastic exercises"; Lyceum students were trained in horse riding, fencing, swimming and rowing. Add to this the daily rise at 7 am, walks in any weather and usually simple food. At the same time, it should be taken into account that the lyceum was a privileged educational institution, which, according to the plan, trained statesmen. In military schools, the requirements for pupils with regard to physical training were incomparably more stringent, and the cadets were treated much more severely.

(True, a lot depended on the personal qualities of the authorities. The kindest old man, Admiral I.F. Kruzenshtern, when he was the director of the naval corps, touchingly took care of the pupils and reproached the officers that “the children are too tired,” which confused the battalion commanders. But this there was, of course, an exception to the rule. Orders in the cadet corps and even in the Smolny Institute for "noble maidens", described, in particular, in the memoirs of P. M. Zhemchuzhnikov and E. N. Vodovozova, are striking in their cruelty; with torture. Of course, it must be borne in mind that information about medicine, hygiene and child psychology was still on average at a very low level, especially in the first half of the 19th century. But it should also be recognized that state educational institutions were focused precisely on this low average level, and not on the ideas of the most humane and enlightened part of society.Thus, the style and methods of education in state educational institutions reflect It is not so much the customs of the nobility that are affected, but the practice of Russian officials from education.) The increased physical hardening of children was partly dictated by living conditions; many boys were expected to serve in the future, any man risked being challenged to a duel. (An expressive example: Pushkin, during his long walks, “carried a cane, the cavity of which was filled with lead, and at the same time periodically threw it up and caught it in the air. So he trained his right hand so that it would not tremble when pointing the gun.) They required physical training such generally accepted entertainments as hunting, horseback riding. At the same time, there was a special chic in the demonstration of physical endurance. A. M. Merinsky, Lermontov’s classmate at the cadet school, recalled: “Lermontov was quite strong, in particular he had great strength in his hands, and he liked to compete in that with the cadet Karachinsky, who was known throughout the school as a wonderful strongman - he bent ramrods and made knots like ropes. He had to pay a lot of money for the damaged ramrods of the hussar carbines to non-commissioned officers who were entrusted with the preservation of state-owned weapons. One day, both of them in the hall were amused by similar tours de force [Manifestations of force (French)], suddenly the director of the school, General Schlippenbach, entered there. What was his surprise when he saw such activities of the junkers. Getting excited, he began to make remarks to them: “Well, aren’t you ashamed to be so childish! Children, or something, you, to be so naughty! .. Go under arrest. They were arrested for one day. After that, Lermontov told us amusingly about the reprimand received by him and Karachinsky. “Good children,” he repeated, “who can knit knots from iron ramrods,” and at the same time burst into loud laughter from the heart.

S. N. Glinka, who studied in the cadet corps in the 80s of the 18th century, recalled: “At a young age, we were accustomed to all air changes and, to strengthen our bodily strength, were forced to jump over ditches, climb and climb high pillars , jump over a wooden horse, climb to heights." Having received such hardening, young people loved to flaunt it. Upon leaving the corps, Glinka and his comrade entered the adjutant to Prince Yu. V. Dolgorukov. Once, in the cold of January, when everyone was wrapping themselves in fur coats, they went to accompany the prince in smart, fitted uniforms. Dolgorukov noted with approval: “Only the Cadets and the devil can endure this!”

However, not only the Cadets were famous for such "youthfulness". Emperor Alexander I himself went on his famous daily walk, le tour imperial, in any weather (and in St. Petersburg it is rarely warm) in one frock coat with silver epaulettes and in a triangular hat with a sultan. The royal children were brought up accordingly. The heir to the throne, the future Emperor Alexander II, just like his peers, every day, not excluding holidays, did gymnastics for at least an hour, learned to ride, swim, row and own weapons. The tsarevich participated in the camps of the cadet corps, and almost no concessions were made for him, although the exercises were very exhausting: long marches on foot in any weather with full gear, coarse soldier food. The heir, obviously, was proud of his endurance and even in winter he constantly walked without gloves, in light clothes.

There were far fewer requirements for girls in this sense, but even they did not cultivate physical effeminacy at all. A.P. Kern was brought up with her cousin A.N. Wolf. In his memoirs of childhood, Kern notes that every day after breakfast they were taken for a walk in the park "regardless of any weather", the governess made them lie on the floor so that "the backs were even", and the clothes were so "light and poor", that Anna Petrovna always remembered how she was freezing in a carriage during a trip to her uncle from Vladimir to Tambov.

Young women were proud of their ability to ride well; the sisters of Natalia Nikolaevna Pushkina, who were excellent masters of this art, with good reason expected to impress the gentlemen of the capital. In the hunting scene in War and Peace, Natasha Rostova, who “dexterously and confidently” sits on her black Arapchik, with her tirelessness arouses the unconditional approval of those around her. “That’s how the young countess,” remarks the uncle with admiration, “departed for a day, at least fit for a man, and as if nothing had happened!”

(In the fate of the Decembrists of a modern person, perhaps in the first place, it is striking that the ladies, accustomed to luxury, voluntarily doomed themselves to material and everyday deprivation. Meanwhile, in the 20s of the 19th century, their act was evaluated primarily as a political act. Yu. M. Lotman, noted that the very [fact of a wife following her husband into exile was not something out of the ordinary in the perception of the Russian nobility. Even in the pre-Petrine era, the family of an exiled boyar, as a rule, followed him into voluntary exile, where her not comfortable living conditions were waiting for.In the Russian army of the 18th - early 19th centuries, the custom was widespread, according to which senior officers, going on a campaign, carried their families in an army wagon train.At the same time, women and children were exposed to a certain danger and undoubtedly experienced considerable hardships In general, Russian noblewomen were both psychologically and physically prepared for the difficulties of life much better than it might seem.)

Pushkin, jealously emphasizing that he fell with a horse, shows concern for his reputation, characteristic of a secular person: a good physical shape was, from this point of view, an important moment.

"ALTHOUGH TERRIBLE FATE I

smitten,

I was not born to feel cowardice.

A. P. Sumarokov. Semira.

The question may arise: what, in fact, is the difference between the training and hardening of noble children from modern physical education? The difference is that physical exercises and loads were designed not only to improve health, but to contribute to the formation of personality. In the general context of ethical and ideological principles, physical tests, as it were, were equated with moral ones. They were equalized in the sense that any difficulties and blows of fate had to be endured courageously, without losing heart and without losing one's own dignity.

Pushkin loved Vyazemsky's poems:

"Under the storm of rock - a hard stone,

In the excitement of passion - a light leaf.

Here, the psychological appearance of a person of that era is perfectly conveyed, in which emotionality and impressionability coexisted with firmness and fortitude. In any case, they should have gotten along. “Failure endured with courage” for Pushkin was a “great and noble spectacle”, and cowardice was for him, it seems, one of the most despised human qualities. It was by no means characteristic of him himself: he endured both moral and physical torments with rare stamina. Having learned about the death of his beloved friend Delvig, shocked by unexpected grief, he nevertheless remarks: “Baratynsky is ill from grief. It's not easy to knock me off my feet." A few years later, the dying Pushkin tried to silently endure the terrible pain, curtly pronouncing: “It’s ridiculous ... what would this ... nonsense ... overpower me ... I don’t want to.”

Of course, such fortitude and courage are determined primarily by the qualities of the individual. But it is impossible not to notice a completely definite ethical attitude, which manifested itself in the behavior of people of the same circle. Where honor was the main stimulus of life, self-control was simply necessary. For example, one had to be able to suppress selfish interests (even quite understandable and justified ones) in oneself if they came into conflict with the requirements of duty.

Petrusha Grinev's father, saying goodbye to his weeping undergrowth, probably worries about him, but does not consider it possible to show it. Such weakness is allowed only for a woman: “Mother in tears ordered me to take care of my health.”

The old man Bolkonsky, seeing off his son to the war, allows himself only such words: “Remember one thing, Prince Andrei: if they kill you, it will hurt the old man ... He suddenly fell silent and suddenly continued in a noisy voice: - and if I find out that you behaved not like the son of Nikolai Bolkonsky, I will be ... ashamed!

Ethical norms here are closely related to etiquette ones: to demonstrate feelings that do not fit into the accepted norm of behavior was not only unworthy, but also indecent. The educator of the heir, V. A. Zhukovsky, anxiously writes in his diary: “To say to. to. (to the Grand Duke - O. M.) about the indecency of the fact that at the slightest sign of illness he gets scared and complains. Let us note that Zhukovsky is not going to somehow calm the suspicious boy, to explain that his health does not cause concern. He is convinced that such behavior is "indecent", shameful, and there can be no indulgence here.