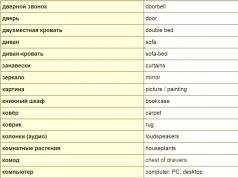

Science as part of the universe undergoes axiological changes (axiology - the theory of values). V. V. Ilyin determined the process of the origin of scientific norms: from reflective, logical-conceptual processing of knowledge and establishing the rationality of the actions taken to the emergence of effective research methods that are built into norms. At the same time, new knowledge has an impact on the existing value scale. In modern conditions, the social forces of society, which have a huge impact on science, are becoming increasingly important. Science is developing comprehensive large-scale social and economic programs for the development of the world, which do not always lead to positive results. As a result of the value transformation of society, not only universal and social values change, but also cultural changes in the value scale in science take place.

Continuity is an indisputable value in science. T. Kuhn attributed to traditions the role of a constructive factor in scientific development, the conditions for the rapid accumulation of knowledge.

Another value of science is usefulness (practical significance). Science, turning into the leading productive force of society, becomes the object of an order from society. Modern science strives not only to create new theories that describe and explain phenomena, but the results of the study are also evaluated in terms of the effectiveness of their use in various areas of social production.

The value of science is evidence, which is associated with the consistency of scientific theories. It makes it possible to describe already known phenomena and predict new ones.

A certain value is the beauty and elegance of the theory, the harmony of the results. According to A. Poincare, the search for the beautiful leads us to the same choice as the search for the useful.

There are moral values of science. G. Merton understands science as a set of values and norms that are reproduced from generation to generation of scientists and are obligatory for a man of science.

The actual scientific values include truth, novelty and originality, continuity, usefulness and beauty.

The regulatory function of truth in scientific knowledge is manifested in the orientation of the scientist to the truth as a result of his activity. Everything should be installed as it really is. It can be argued that it is the value orientation to obtain the truth that determines the specifics of scientific research. At the same time, there are certain problems in the criteria for the truth of knowledge, specific differences between the truths of the natural and human sciences (although recently there has been some convergence of them, and the natural sciences are forced to use humanitarian definitions of truth), etc.

In modern science, novelty and originality of problems, ideas, hypotheses, theories, etc. acquire value. New ideas expand the problematic field of science, contribute to the formulation of new tasks that determine the direction of scientific knowledge. Original ideas are especially valuable because not every scientist is able to come up with them. At the same time, conservative tendencies are quite strong in science. It is they who provide protection against implausible ideas.

The science – it is a sphere of human activity aimed at the production and theoretical systematization of objective knowledge about nature, society and knowledge itself. It is a complex socio-cultural phenomenon, which acts as: 1) a system of reliable knowledge about various spheres of the world; 2) activities for the production of such knowledge; 3) a special social institution.

Like a knowledge system science is a collection of various information about the world, united in a strict and logical orderly integrity. Such a system includes various forms of knowledge - facts, problems, hypotheses, laws, theories, scientific pictures of the world, ideals and norms of science and its philosophical foundations.

Science as a special kind of knowledge is an active purposeful activity of researchers, focused on obtaining fundamentally new knowledge about a particular area of the world, the laws of its functioning and development. This activity is characterized by: the development and use of scientific research methods, the use of special equipment (instruments, instruments, laboratories, etc.), the assimilation and processing of extensive information (libraries, databases, etc.).

As social institution science appears as a system of special institutions (Academies, research institutes, higher educational institutions, laboratories, etc.), professional teams and specialists, various forms of communication between them (scientific publications, conferences, internships, etc.). All this taken together ensures the very existence of science in modern society, its functioning and improvement.

As an integral system, science arose in the 16th-17th centuries, in the era of the formation of the capitalist mode of production. The development of industry required the knowledge of objective laws and their theoretical description. With the advent of Newtonian mechanics, science acquired a classical form of an interconnected system of applied and theoretical (fundamental) knowledge with access to practice. Reflecting the diversity of the world, science is divided into many branches of knowledge (private sciences), which differ from each other in what side of reality they study. According to the subject and method of cognition, one can single out the sciences about nature - natural science; society - social science (humanities, social sciences); cognition and thinking - logic and epistemology. Technical sciences and mathematics are separated into separate groups. According to the direction of scientific disciplines, according to their relation to practice, it is customary to distinguish between fundamental and applied sciences. Fundamental sciences are engaged in the knowledge of regular relationships between the phenomena of reality. The immediate goal of applied research is to apply the results of fundamental sciences to solve technical, industrial, social problems.

The role of science in the life of modern society is characterized by the following main features:

– cultural and ideological- science produces true knowledge, which is the foundation of the modern worldview and a significant component of spiritual culture (education and upbringing of a person is impossible today without mastering the main achievements of science);

– immediate productive force- the most important achievements of technical and technological progress are the practical implementation of scientific knowledge;

– social strength- science is being introduced today into various spheres of public life, directs and organizes almost all types of human activity, makes a significant contribution to the solution of social problems (for example, global problems of our time).

The growing role of science and scientific knowledge in the modern world, the complexity and contradictions of this process gave rise to two opposite positions in its assessment - scientism and anti-scientism, which had already developed by the middle of the 20th century. Scientists argue that "science is above all" and it must be implemented in every possible way as a standard and absolute social value in all types of human activity. Anti-scientism is a philosophical and ideological position, whose supporters sharply criticize science and technology, which are not able to ensure social progress, because they are forces that are hostile to the true essence of man, destroying culture. Undoubtedly, it is equally wrong to both exorbitantly absolutize science and underestimate, and even more so completely reject it. It is necessary to objectively, comprehensively assess the role of science, to see the contradictions in the process of its development.

Ethos of science- a set of values and norms accepted in the scientific community and determining the behavior of scientists. These include:

universalism - a scientist should be guided by the general criteria and rules for scientific research and scientific knowledge (orientation towards objectivity, verifiability and reliability of scientific statements);

generality - the results of scientific research should be considered as the common property of members of the scientific community;

disinterest - the desire for truth should be the main thing in the activity of a scientist and not depend on various extra-scientific factors;

· organized skepticism - criticality and self-criticism in the assessment of scientific achievements.

Today an attempt has been made to develop a kind of moral code of a scientist by including new ethical norms:

Civil and moral responsibility of a scientist for the consequences of his discoveries;

No right to a dangerous experiment;

A conscientious attitude to scientific work, including responsibility for the quality of the information received, a ban on plagiarism, respect for the scientific results of predecessors and colleagues;

Resolving scientific disputes exclusively by scientific means, without developing theoretical disagreements into personal hostility;

Responsibility for the education of scientific youth in the spirit of humanism, democratic norms, scientific honesty and decency.

Scientific revolutions and change of types of rationality. Scientific knowledge is characterized by a tendency to constant development. On the question of the dynamics of scientific knowledge, there are two opposite approaches: cumulative and anti-cumulative. Cumulative- a model for the development of scientific knowledge, according to which it is a continuous process of increasing new knowledge based on the existing one by gradually adding new provisions to the accumulated amount of knowledge. Anticumulativeism believes that there are no enduring components in the development of knowledge. The transition from one stage in the development of science to another is associated with a revision of fundamental ideas and methods. The history of science is presented as a struggle and change of theories and methods, between which there is neither logical nor meaningful continuity; hence the thesis about the incommensurability of scientific theories (T. Kuhn, P. Feyerabend).

Since the 1960s, a prominent role has been played in the philosophy of science Thomas Kuhn's theory of scientific revolutions. He singled out periods of "normal science" and periods of scientific revolution in the history of science. In the period of "normal science" research is subject to a paradigm. Paradigms (Greek παράδειγμα - sample, model, example) are “generally recognized scientific achievements that, for a certain time, provide the scientific community with a model for posing problems and their solutions.” During the "normal science" period, members of the scientific community engage in paradigm-based puzzle solving. Exceptional situations in which there is a change in professional norms are scientific revolutions. There is a change in the conceptual grid through which scientists view the world, a new paradigm is established, and the period of normal science begins again.

In the course of scientific revolutions, paradigms (patterns) for explaining and describing research results in entire scientific fields, such as physics, biology, etc., have changed. At the same time, as V. S. Stepin proves, a phenomenon of a more global order was taking place - a change in the types of rationality of all science. Type of scientific rationality – these are the ideals of cognitive activity that prevail at a certain stage in the development of science, in other words, ideas about how to properly build the relationship “subject - means of research - object” in order to obtain objective truth. At different stages of the historical development of science, coming after scientific revolutions, its own type of scientific rationality dominated: classical, non-classical, post-non-classical.

classical rationality characteristic of the science of the XVII-XIX centuries, which sought to ensure the objectivity and objectivity of scientific knowledge. The object style of thinking dominated, the desire to know the subject in itself, regardless of the conditions of its study. Objects were considered as small systems (mechanical devices) having a relatively small number of elements with their force interactions; causality was interpreted in the spirit of mechanistic determinism.

Non-classical rationality prevailed in science in the period from the end of the 19th to the middle of the 20th century. Revolutionary changes took place in physics (the discovery of the divisibility of the atom, relativistic and quantum theories), in cosmology (the concept of a non-stationary Universe), in chemistry (quantum chemistry), in biology (the formation of genetics), cybernetics and systems theory arose. Non-classical rationality moved away from the objectivism of classical science, began to take into account that ideas about reality depend on the means of its cognition and on the subjective factors of research. At the same time, the reproduction of the relationship between the subject and the object began to be considered as a condition for an objectively true description and explanation of reality.

Post-nonclassical scientific rationality has been developing since the second half of the 20th century. It takes into account the fact that knowledge about an object is correlated not only with the features of its interaction with the means (and, therefore, with the subject using these means), but also with the value-target settings of the subject. It is recognized that the subject influences the content of knowledge about the object not only due to the use of special research tools and procedures, but also due to its value-normative attitudes, which are directly related to extra-scientific, social values and goals. In addition, in post-nonclassical rationality, the subject, means and object of cognition are considered as historically changing. A characteristic feature of post-nonclassical rationality is also the complex nature of scientific activity, the involvement in solving scientific problems of knowledge and methods inherent in different disciplines and branches of science (natural, humanitarian, technical) and its different levels (fundamental and applied).

Question #45

The category of value in the philosophy of science:

values in cognition as a form of manifestation of the socio-cultural conditioning of knowledge

The term " value"extremely meaningful,today, but in most cases value is understood as significance for the individual and society.

As a rule, the subject of a value relation is a person, a social group, society as a whole, but with the advent of system-structural methodology, the concept of value began to be applied to systems that do not include a person, as a parameter of a goal-setting system.carrying out evaluation and selection procedures.

As applied to the cognitive process, the concept of "value" also turned out to be ambiguous, multifaceted, fixing different axiological content.

- This is, firstly, emotionally coloredattitude containing interests, preferences, attitudes etc., formed by a scientist under the influence moral, aesthetic, religious — sociocultural factors in general.

- Secondly, this value orientations within cognition itself, including worldview painted, on the basis of which the forms and methods of description and explanation, evidence, organization of knowledge are evaluated and selected, for example scientific criteria, ideals and norms of research .

- Thirdly, values in knowledge is objectively true subjectknowledge (fact, law, hypothesis, theory) and effective operational knowledge (scientific methods, regulatory principles), which, precisely because of the truth, correctness, information content, acquire significance and value for society.

Throughout the 20th century, there was a discussion in the philosophy of science about the role of values in science: are they a necessary “driving force” for the development of science, or is it a condition for the successful activity of scientists to free them from all possible value orientations? Is it possible to completely exclude value preferences from judgments of facts and to know the object as such, in itself? The answers to these questions and the introduction of terminology and ways of reasoning about this problem are presented by Kant, who distinguished between the world of existence and the world of due, by neo-Kantians, in the works of M. Weber, who studied the difference between scientific and value.

|

By Cantu, theoretical (scientific) reason is aimed at the knowledge of the "world of existence", practical reason(moral consciousness) addressed to the "world of due" - norms, rules, values. This world is dominated by the moral law, absolute freedom and justice, human striving for goodness. So, a scientist as a bearer of theoretical reason must have a moral way of thinking, have a critical self-esteem, a high sense of duty and humanistic convictions. The doctrine of values, or axiology as applied to scientific knowledge, was fundamentally developed by the German philosopher G. Rickert. The philosopher proceeds from the fact that values are an "independent kingdom", respectively, the world does not consist of subjects and objects, but of reality as the original integrity of human life and values. Recognition of an independent world of values is a metaphorically expressed desire to affirm the objective (non-subjective) nature of values, a way of expressing its independence from the subject’s everyday evaluative activity, which depends, in particular, on education, taste, habits, access to information and other factors. The special role of historical science, which studies the process of crystallization of values in the benefits of culture, is revealed, and only by examining historical material can philosophy approach the world of values. One of the main procedures for the philosophical comprehension of values is to extract them from culture, but this is possible only with their simultaneous interpretation and interpretation. Renowned German historian, sociologist and economist M. Weber studied the problem of values also directly at the level of scientific knowledge, distinguishing between the natural and social sciences and the humanities and their ways of solving the problem of "science's freedom from values". There are various possibilities for the value correlation of an object, while the attitude towards the object correlated with value does not have to be positive. If in qualityThe nature of the objects of interpretation will be, for example, “Capital” by K. Marx, “Faust” by J. Goethe, the Sistine Chapel by Raphael, “Confession” by J.J. Rousseau, then the general formal element of such an interpretation - the meaning will be to reveal to us possible points of view and the direction of assessments. If the interpretation follows the norms of thought adopted in any doctrine, then this forces one to accept a certain assessment as the only "scientifically" acceptable one in such an interpretation, as, for example, in Marx's "Capital". Value analysis, considering objects, refers them to a value independent of a purely historical, causal meaning, which is outside the historical. |

Today, values are understood not only as the “world of due”, moral and aesthetic ideals, but also any phenomena of consciousness and even objects from the “world of existence” that have one or another worldview and normative significance for the subject and society as a whole. A significant expansion and deepening of axiological issues as a whole also occurred due to the recognition that various cognitive and methodological forms - truth, method, theory, fact, principles of objectivity, validity, evidence, etc. - themselves received not only a cognitive, but also a value status. Thus, it became necessary to distinguish two groups of values functioning in scientific knowledge

:

- first - sociocultural, worldview values conditioned by the social and cultural-historical nature of science and scientific communities, the researchers themselves;

- second - cognitive-methodological values , performing regulatory functions, determining the choice of theories and methods, methods of nominating, substantiating and testing hypotheses, evaluating the grounds for interpretations, the empirical and informative significance of data.

D In recent decades, science has been predominantly viewed only asthe static structure of knowledge that has become, i.e. activity and socio-historical aspects were eliminated.Today the situation is significantly different. Studies of science as a unity of knowledge and activities to develop this knowledge have brought to the forefront the problem of regulators of cognitive activity, i.e. its value-normative prerequisites and driving forces, as well as the mechanisms of their change and replacement of some by others.

The desire to identify the structure of developing scientific knowledge and consider it systematically led to the realization of the need to connect new "units" of methodological analysis - a system of various conceptual preconditions ( sociocultural, worldview) inshape and form philosophical and general scientific methodological principles for constructing a scientific picture of the world, the style of scientific thinking, ideals and norms of cognitive activity, common sense etc.

Thus XX century proved that science cannot bestrictly objective, independent of the subject of knowledge, free from value aspects, because as a social institution it is included in the system of economic, socio-political, spiritual relations that exist in a particular historical type of society. Science, going hand in hand with humanistic morality, turns into a great blessing for all living, while science, indifferent to the consequences of its own deeds, unambiguously turns into destruction and evil.(for example, the creation of weapons of mass destruction, the use of genetically modified substances, the growing pollution of air, water, soil, the depletion of natural resources, etc.).

One of the fruitful ways of meaningful concretization values and value orientations in science is their interpretreat as a historically changing system of norms and ideals of knowledge . Values of this kind underlie scientific research, and one can trace a fairly definite relationship between cognitive attitudes proper and social ideals and norms; establish the dependence of cognitive ideals and norms both on the specifics of the objects studied at one time or another by science, and on the characteristics of the culture of each historical era.

In this case, scientific knowledge is already understood as an active reflection of the objective world, determined in its development not only by the features of the object, but also by historically established prerequisites and means; as a process oriented by worldview structures and values that lie at the foundation of a historically defined culture.

Such an understanding makes it possible to reveal deeper levels of value conditioning of cognitive processes, to substantiate their organic "merging".

|

EPISTEMOLOGY (Greek episteme - knowledge, logos - teaching) - philosophical - methodological discipline that studies knowledge as such, its structure, structure, functioning and development. Traditionally identified with the theory of knowledge. |

The epistemological problem is to understand how the value-laden activity of the subject can perform constructive functions in cognition. To solve this problem, the most fruitful is the search and identification of adequate means and mechanisms which are developed within the very scientific knowledge and can serve to eliminate deformations coming from the subject, distortions under the influence of personal and group tendentiousness, prejudices, addictions, etc. Nonetheless activity itself

value-oriented subject of knowledge based on the objectlaws, becomes a decisive determinative factor in the field of scientific knowledge and the main condition for obtaining objectively true knowledge in specificsocio-historical conditions.

The "presence of man" in the traditional forms and methods of scientific knowledge is becoming more and more recognized; discovered axiological, value aspects in the formation and functioning of scientific methods. |

To understand the dialectics of the cognitive and the value, one must first of all be aware of the existing in society and science methods and methods of formation of the subject of scientific activity - its socialization

. One of the fundamental characteristics of the subject of scientific activity is its sociality, which has an objective basis in the universal nature of scientific work, which is due to the cumulative work of previous and contemporary scientists of the subject. Sociality is not a factor external to a person, it is from within determines his consciousness, penetrating and "naturalizing" in the process of personality formation as a whole.

General form of socialization

Socialization is carried out through language and speech; through knowledge systems, which are theoretically conscious and formalized as a result of social practice; through the value system, and finally through the organization of individual practice society forms both the content and the form of the individual consciousness of each person.

Rational-regulatory form of socialization

subject of scientific activity

Along with general laws, the socialization of the subject of scientific activity includes a number of special ones. The most important mechanism of socialization of the subject of scientific activity is the assimilation by him of generally recognized and standardized norms and rules of this activity. in which the historical experience of society in scientific and cognitive activity and communication in the field of this activity is generalized and crystallized. The scientist is prescribed certain ways to achieve goals, the proper form and nature of relations in the professional group are set, and his activities and behavior are evaluated in accordance with the samples and standards accepted in the scientific team. Thus, to a large extent, subjective-irrationalistic, indefinitely-arbitrary moments in his professional behavior are removed, primarily directly in the research process.

Socio-historical form of socialization

subject of scientific activity

Obviously, rational forms of such regulation of the activity of the subject of scientific activity are necessary and, in addition, require their coordination with other methods of ordering activity that are not reduced to direct, direct regulation and regulation as such. This refers to a system of both cognitive and worldview, ethical and aesthetic values that perform orienting functions in the search activity of the researcher, as well as a way of seeing (paradigm) - one of the most important socio-psychological characteristics of the subject of scientific activity from the point of view of his belonging to the scientific community . The scientist's way of seeing is not limited to purely psychological features of perception. It is also conditioned by social factors, primarily professional and cultural-historical ones.

Science is in the same space of culture and society with all other activities that pursue their own interests, are influenced by power, ideologies, political choices, require recognition of responsibility - hence the impossibility of neutrality and detachment for science itself. But at the same time, one kind of neutrality must be preserved - the neutrality of science as knowledge, which requires objectivity and a certain autonomy.

Value orientations in science are manifested in passions, goals, interests, motives, emotions, ideals, etc., inherent in the cognizing subject. Value factors are expressed in any form of significance for the researcher: the subject, the process, and the result of cognition. This significance can be cognitive, practical, technical, spiritual, methodological, ideological, social, etc. Before talking about the specifics of value factors in social and humanitarian cognition, let us single out the value orientations of scientific cognition in general (both natural science and socio-humanitarian).

- 1) The first aspect: the value factors of the objective side of cognition value characterize what cognitive activity is aimed at, what arouses at least cognitive interest, although other interests may be behind cognitive interest. The study of the "problems of globalization", "the specifics of the artistic understanding of the world", "the impact of the latest information technologies on a person", etc., is obviously socially and (or) personally determined. It should be stated that the subjects of research, the goals of cognition, identified in the diverse world, are value-conditioned. To know something, you need to want to know it, to be interested in learning about it. Thus, axiological components are a prerequisite for any knowledge.

- 2) Let us designate the second aspect of value factors as procedural value orientations. These include ideals and norms for describing knowledge, its organization, substantiation, evidence, explanation, construction, etc. This aspect of value factors answers the question of how knowledge should be obtained, its proof, and characterizes cognitive activity as such. This type of value orientations, of course, intrudes into the sphere of epistemology and methodology, but it does not replace it. Methodological and epistemological techniques are aimed at revealing the objective relationship between objects and phenomena. However, the choice of methods of cognitive activity is determined by values and depends to some extent on the researcher. Methods of cognition and substantiation of knowledge are of a normative nature, their perfect functioning is given in ideal forms. It is no coincidence that the methodological procedures of substantiation, explanation, evidence, etc. characterized as the ideals and norms of science. Procedural value orientations are determined by the objects of cognition, sociocultural factors, the practice of cognition and the application of knowledge. They are historically variable. Thus, the scholastic method of organizing and substantiating knowledge, characteristic of the Middle Ages, is supplanted in modern times by the ideal of empirical substantiation of knowledge.

- 3) The third aspect of value factors is connected with the result of cognition, its ultimate goal. The result of scientific knowledge must be objective, justified. It must be true. Truth is the main goal of cognition, its fundamental ideal, a specific category of precisely scientific cognition. Without truth there is no science. Truth in the most general sense is the correspondence of knowledge and the object of knowledge. Truth is an ideal, because it is impossible to achieve the absolute identity of knowledge and reality, and the concept of the ideal of truth fixes in itself the ultimate harmony of knowledge and reality. This aspect of value factors includes such important ideals of knowledge as beauty, simplicity, unity. (In a broad sense, these ideals are actualized throughout the entire process of cognition.) These characteristics of knowledge indirectly reflect certain properties of objective reality in the mind of the researcher and act as value-epistemological guidelines, performing pre-criteria and regulatory functions in cognition. For example, the beauty of knowledge, the beauty of truth subjectively signal to the researcher about the interrelationships of facts or elements of knowledge that have an objective (epistemological) value. A. Einstein attributed the feeling of beauty to the number of different ways of comprehending the truth. W. Heisenberg believed that the "brilliance of beauty" allows one to guess the "radiance of truth".

- 4) The fourth aspect of value orientations is associated with external and internal factors of cognition. The external value orientations of knowledge should include the social responsibility of science, material, ambitious, ideological, national, religious, universal and other interests. The internal value orientations should include the orientations of the three aspects of cognition described above, as well as ethical norms and values of cognitive activity: moral requirements - research honesty, obtaining new knowledge, disinterested search and upholding of truth, prohibition of plagiarism, etc. These factors largely coincide with what is called the ethos of science.

- 5) We include heuristic and non-heuristic orientations in the fifth aspect of value factors. Heuristics are orientations that, to one degree or another, help to obtain the desired solution, acting as a kind of hint, a tip for the researcher.

An example of such orientations are the ideals of beauty, harmony, unity, simplicity of knowledge. Non-heuristic value factors primarily include ethical norms and values, as well as all external value orientations of cognition. Non-heuristic values act as motivating or inhibiting principles of cognition. They can lead to the stimulation of cognition or its rejection, to the distortion of knowledge, they act as a strong-willed, "energetic" basis of cognition. However, they are not able to suggest any properties, contours, trends of new knowledge. For example, an objective search for truth is impossible without scientific conscientiousness, but scientific conscientiousness by itself cannot find it. This requires epistemological, methodological and heuristic foundations.

Researching values axiology. The problem of intra-scientific values is connected with reflection on those theoretical, methodological, worldview and practical consequences that followed from the rapid development of science. This issue was aimed at realizing the need for an organic intellectual expansion of science into the world of human relations as a whole, at understanding the fact that scientific knowledge is not a sphere of monopoly of human existence and cannot dominate complex meaningful life orientations. In the diverse contexts of human relations, the concepts of good-evil, beautiful-ugly, fair-unfair, useful-harmful are of paramount importance. Modern methodologists have come to the conclusion that value and evaluation aspects cannot be removed from the sphere of scientific knowledge. Scientific knowledge is regulated not only by the mechanisms of intellectual activity, but also by influences coming from the world of values.

Intrascientific values(= cognitive) perform orientation and regulatory functions. These include: methodological norms and procedures for scientific research; methodology for conducting experiments; evaluation of the results of scientific activity and the ideals of scientific research; ethical imperatives of the scientific community. Intra-scientific values are greatly influenced by the value system prevailing in a particular society. The intrinsic value of science is considered to be an adequate description, a consistent explanation, reasoned proof, substantiation, as well as a clear, logically ordered system of construction or organization of scientific knowledge. All these characteristics are associated with the style of scientific thinking of the era and are largely socially determined.

social values embodied in social institutions and rooted in the structure of society. They are demonstrated in programs, resolutions, government documents, laws and are expressed in a certain way in the practice of real relations. Social institutions provide support for those activities that are based on values acceptable to a given structure. Social values can act as a basis for criticizing scientific research, they can act as criteria for choosing standards of behavior. They are woven into public life, claim to be universally significant. Social values are aimed at setting the principles for the stable existence of society, ensuring the efficiency of its life.

The intersection of social and intra-scientific values is well shown by K. Popper. The idea of demarcation - the separation of science and non-science, carried out by him in epistemology, had an effect far beyond the scope of purely scientific knowledge. The central idea of falsification in Popper's epistemology, which acts as a criterion of scientific character (what can be refuted in principle is scientific, and what is not is dogma), required self-correction from the social organism. The idea of falsification, which plays a huge role in the entire modern philosophy of science, when applied to social analysis, sets very significant guidelines for the self-correction of the social whole, which are extremely relevant in relation to the realities of life. From the point of view of falsification, politicians should only strive to ensure that their projects are analyzed in as much detail as possible and submitted to critical refutation. Uncovered mistakes and miscalculations will lead to more viable socio-political decisions adequate to the objective conditions.

The paradox of science lies in the fact that, while declaring itself to be the real basis of social progress, contributing to the well-being of mankind, it at the same time led to consequences that are a threat to its very existence. The expansion of technogenic development, environmental pollution, and the avalanche-like growth of scientific information turn out to be pathogenic factors for people's lives.

Mankind faces the problem of realizing its helplessness in controlling the ever-increasing technical power of modern civilization. Neglect of spiritual values in the name of material ones has a depressing effect on the development of the individual. In contrast to the values of the consumer society in public life, there are other values of civil society aimed at upholding freedom of speech, principled criticism, justice, the right to education and professional recognition, the values of scientific rationality and harmonious life. In a situation of widespread recognition of the dehumanization of modern science, the axiological-deductive system of theoretical description of phenomena and processes, which takes into account the interests and parameters of human existence, is of particular value.

===================================================================================================================

Values- these are specific social characteristics of objects that reveal their positive value for a person and society.

social values exist at the level of society as a whole.

Classification of social values:

· Material (human needs for food, housing, clothing, the desire for well-being);

· Spiritual: - scientific (truth);

Aesthetic (beauty);

Moral (goodness, justice);

Religious.

Intrascientific values - examples of description, explanation, scientific evidence.

1. Methodological ideals, norms, dominant paradigms in science and research programs.

· mathematical ideal of scientific character (Euclid, Descartes). From the initial axioms, deductive derivation of logical consequences is carried out. Criteria: rigor, consistency, completeness, evidence, immutability of conclusions.

· the physical ideal of scientific character (Newton, Bacon): an adequate description and explanation based on experiment, as well as using the logical and mathematical apparatus. The theory is built using the hypothetical-deductive method.

· humanitarian ideal of science. Social cognition is carried out through the prism of values and norms. The subject of humanitarian knowledge is included in the system of social relations that he studies.

2. Experimental technique. The role of mathematical modeling and statistical and probabilistic methods is growing.

3. Evaluation of the results of scientific activity. Criteria: logical provability, experimental verifiability.

4. Ethical ties of the scientific community: the inadmissibility of plagiarism.

Social and intra-scientific values are dialectically interconnected.

The harmonious development of science can only be achieved when both the needs of society and the values of science itself are taken into account. Supporters of externalism, or the impact of external factors on science, believe that the driving forces of scientific progress are the needs of society, because it is it that sets certain goals for science. The main disadvantage of this view is the underestimation of the relative independence of the development of science, which is expressed in the continuity of its ideas, in the preservation of all firmly substantiated scientific knowledge, as well as in its generalization and development. Therefore, internalists emphasize the decisive role of intrascientific values. It may even seem that science develops purely logically by generalization, extrapolation and specification of already known concepts and theories. With the growth of the theoretical level of the study of its objects, science acquires an ever greater relative independence of development. Nevertheless, the separation of science from the real world and from diverse connections with other spheres of culture ultimately leads to its stagnation and degeneration. That is why, despite the importance of the intra-scientific values of science, one should never forget that science should serve society.