Relations with nomads were one of the most difficult tasks of the foreign policy of Kievan Rus. The nomadic element manifested itself as a constant factor in ancient Russian history, acting as an active, offensive, but at the same time changeable force.

The struggle against the raids of nomads was costly for the inhabitants of the southeastern part of the country.

In the VIII-IX centuries. the territory of the chronicle "obrov" (Avars) in the Black Sea steppes from the Danube to the Don was occupied by the Turkic-speaking nomads - the Pechenegs. Under 915, the "Tale of Bygone Years" reports that the Pechenegs first came to the Russian land and, having made peace with Prince Igor, went to the Danube. This was the first Russian-Pechenezh treaty. However, the relations of Rus with the Pechenegs were manifested both in wars and in allied relations. The Pechenegs were the object of active Byzantine diplomacy, which viewed nomads as a counterweight to Russia. Kiev tried to carry out the same diplomacy. If in 920 Igor fought with the Pechenegs, then in 944 he "hired them" for a campaign against Byzantium. But when Svyatoslav was with troops in Bulgaria, the Pechenegs besieged Kiev, although they later lifted the siege, fearing that the prince would "destroy" them. Returning from the Danube, Svyatoslav "gathered the warriors and drove the Pechenegs into the field, and there was peace." Perhaps, in accordance with his terms, the Pechenegs participated in the next campaign of Svyatoslav against Bulgaria, but not all: some of the nomads were bribed by Byzantium. They, led by Khan Kurey, closed the mouth of the Dnieper and killed the Russian squads. It was at this time that the greatest activity of the Pechenezh hordes took place, which occupied the regions north of the Ros River.

At the end of the X century. the fight against nomads has become an urgent need for Russia. Each of their raids led to the destruction of villages and arable lands, the capture of "polon". Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavich managed to make the defense of Russia not only a state, but also a national matter. Under him, relations with the Pechenegs stabilized. He began to build cities along the Desna, Sturgeon, Trubezh, Sule, Stugna. " As a result, the first notch line was built to the east of Kiev.

Svyatopolk Vladimirovich, on the contrary, was in alliance with the Pechenegs. They constituted a significant part of his hired squad, but were defeated by the Varangian-Novgorod army of Yaroslav in 1018. The Pechenegs intervened in the dynastic struggle. Taking this into account, Yaroslav in 1032 "began to build cities along the Ros". As a result, the territory was occupied, which for a long time was considered neutral, separating the Russian borders from the steppe. Trying to gain a foothold on the former borders, the Pechenegs in 1036 undertook a large campaign against Kiev. Gathering the Novgorod-Varangian army and annexing the Kiev squads to it, Yaroslav defeated the Pechenegs. Yaroslav's victory was the last major battle with the Pechenegs and in fact decided their future fate. Squeezed between the Russians and the Polovtsy advancing from the east, the Pechenegs turned into a passive ethnic element. Some of them disappeared into the Cumans, some went to the Balkans. A significant part of the Pechenezh tribes submitted to Russia and settled on lands near the steppe borderlands. Later, mingling with other nomadic peoples, they received the name "black hoods" and carried out guard duty, guarding the Russian borders.

From the middle of the XI century. The most dangerous opponents of Russia were the Turkic nomads - the Polovtsians (Kipchaks, Cumans).

They came from across the Volga to the steppes of the Northern Black Sea region and drove out the Pechenegs who roamed there. The vast territory occupied by them received the name "Polovtsian steppe" in Russian chronicles. From here, the Polovtsian hordes began invasions of the southern Russian volosts adjacent to the steppes - Kiev, Pereyaslav, Chernigovo-Severskaya. In the "Tale of Bygone Years," the Polovtsians were first mentioned under 1056. Led by Khan Bolush, they came to Russia, and "Vsevolod made peace with them, and the Polovtsians returned to where they came from." However, despite the concluded peace, in 1061 they first "fought" Russia, defeating the troops of Vsevolod. The Yaroslavich brothers, Izyaslav, Svyatoslav and Vsevolod, who fled from the battlefield near the Alta River in 1068, suffered a crushing defeat from the Polovtsians. captured Sharukan Khan. The Polovtsian raids on the Russian lands were frequent and devastating, "the army is great ... from the Polovtsians everywhere" - noted the chronicler.

The security of Russia required the inclusion of the Polovtsian steppe in vassal dependence. However, the dynastic conflicts of the princes, as well as the lack of unity among the Polovtsian khans, prevented this. Offended by the Polovtsian ambassadors, repeatedly beaten in battles, the Kiev prince Svyatopolk in 1094 was able to conclude peace with the Polovtsians, having married the daughter of Khan Tugorkhan. Since that time, the policy of Russia in relation to the steppe has become more complex and flexible. It is associated with the activities of the Pereyaslavl, and then the great Kiev prince Vladimir Monomakh. His policy of a systematic and active offensive against the Polovtsians was approved at the Dolobian Congress of Princes in 1103.

The tactics proposed by Monomakh was to transfer the war with the Polovtsy to the steppe nomad camps, without waiting for their forays into Russia. The struggle of Monomakh with the Polovtsy was inevitable for him, since he owned the Pereyaslavl principality bordering the steppe, but at the same time the prince managed to turn it into a common cause uniting Russia. For the organization of joint campaigns "on the nasty" he spared no effort; such campaigns were undertaken in 1103, 1109, 1110, 1111. They brought Monomakh the glory of a national hero and victor, won over the Kievan boyars to his side, and ultimately contributed to his establishment on the grand prince's throne. In addition, the struggle against the Polovtsian danger united and consolidated Russia, internal contradictions were transferred to the steppe, and the Kiev boyars had the right to shout at the warring princes: “Why do you have feuds among yourself? And the nasty ones are ruining the Russian land! "

From the second third of the XII century. separatist tendencies became decisive both in the internal political development of the Russian lands and in relations with the steppe. General campaigns against the Cumans are becoming rare. Thus, the campaign undertaken in 1185 by the Seversk princes ended not only with their defeat and captivity, but led to the ruin of Pereyaslavl and Putivl by Khan Konchak. The details of these events are set forth by the chronicler and sung by an unknown author in "The Lay of Igor's Host."

The Polovtsi became active participants in the internecine struggle of the appanage princes, who turned to them for military assistance, set them on their enemies, for the sake of a fragile alliance, they married the khan's daughters. Vladimir Monomakh's cousin Oleg, who was expressively called "Gorislavich" by his contemporaries, became especially famous for his friendship with the Polovtsian khans. These circumstances objectively led to the strengthening of the Polovtsian khans. “Almost two centuries of the struggle between Russia and the Polovtsy has its significance in European history,” noted V.O. Klyuchevsky. While Western Europe undertook an offensive struggle against the Asian East with crusades, Russia covered the left flank of the European offensive with its struggle against the steppe. However, this historical merit of Russia cost it dearly. "

882-912 - Oleg's reign in Kiev.

907 - Oleg's campaign to Constantinople. The first treaty between Russia and Byzantium on friendly relations, norms of mutual trade and navigation (according to chronicles).

911 - Oleg's second campaign against Constantinople. A new treaty between Russia and Byzantium (according to chronicles).

912-945 - Igor's reign in Kiev.

915 - the arrival of the Pechenegs to Russia (the first mention in the "Tale of Bygone Years").

941 - the first campaign of Prince Igor against Constantinople, which ended in failure.

944 - the second campaign of Prince Igor against Constantinople. The treaty between Russia and Byzantium (Russia lost the rights of duty-free trade and undertook to provide assistance in the protection of Byzantium's border possessions).

945 - the uprising of the Drevlyans. The murder of Prince Igor of Kiev.

945-964 - the reign of Princess Olga in Kiev (after the murder of her husband Prince Igor by the Drevlyans).

947 - tax reform.

Around 957 - the embassy of Princess Olga to Constantinople, her adoption of Christianity (under the name Elena).

945-972 (or 973) - the reign of Svyatoslav Igorevich in Kiev.

965 - defeat of the Khazar Kaganate by Svyatoslav (on the Lower Volga). Establishing control over the Volga trade route.

968-971 - campaigns of Prince Svyatoslav to Danube Bulgaria. Wars with Byzantium and the Pechenegs.

968 (969) - the defeat of the Pechenegs near Kiev.

971 - Treaty between Russia and Byzantium.

972 - the death of Prince Svyatoslav in a battle with the Pechenegs at the Dnieper rapids.

972 (or 973) -980 - civil strife in Kiev after the murder of Prince Svyatoslav by the Pechenegs. The reign of Yaropolk.

980-1015 - reign of Vladimir I Svyatoslavich in Kiev.

980 - Creation of a single pantheon of pagan gods in Kiev.

981 - the victorious campaign of the Russian army on the "Cherven Grady".

985 - the campaign of Prince Vladimir against the Volga Bulgars.

988-989 - Baptism of Rus.

1015-1019 - the internecine wars of the sons of Vladimir I for the grand prince's throne.

1015 - uprising against the Varangians in Novgorod. Compilation of the code of laws "Yaroslav's Pravda" - the most ancient part of "Russian Pravda".

1016-1018, 1019-1054 - the reign of Yaroslav the Wise in Kiev.

1024 - an uprising in the Rostov-Suzdal land, suppressed by Prince Yaroslav the Wise.

1026. Partition of Rus between Yaroslav the Wise and his brother Mstislav along the Dnieper: the Right Bank (with Kiev) went to Yaroslav, the Left Bank (from Chernigov) to Mstislav.

1036 - the victory of Prince Yaroslav the Wise over the Pechenegs, which provided Russia with peace for a quarter of a century (before the Polovtsy came to the steppe).

1043 - the last campaign of the troops of Russia (led by the son of Yaroslav the Wise Vladimir Yaroslavich Novgorodsky) to Constantinople, which ended in failure.

1054-1068, 1069-1073, 1077-1078. 1054-1073. The great reign of Izyaslav Yaroslavich in Kiev.

1060 - the campaign of the Yaroslavich princes against the Torks.

1068 - the first major Polovtsian foray into Russia. The defeat of the Yaroslavich princes on the Alta River. The uprising of the townspeople in Kiev. Flight of Izyaslav to Poland. The proclamation of Vseslav Bryachislavich of Polotsk by the Kiev prince.

About 1071 - uprisings in Novgorod and Rostov-Suzdal land.

1072 - Vyshgorodsky Congress of Princes. Compilation of "Pravda Yaroslavichi" - the second part of "Russian Pravda".

1073-1076 - the great reign of Svyatoslav Yaroslavich in Kiev.

1076, 1078-1093. - the great reign of Vsevolod Yaroslavich in Kiev.

1093-1113 - the great reign of Svyatopolk Izyaslavich in Kiev.

1097 - Lyubech Congress of Princes.

1103 - Dolobsky congress of princes to prepare a campaign against the Polovtsians. Campaign of princes Svyatopolk and Vladimir Monomakh against the Polovtsians.

1111 - the campaign of the Russian princes against the Polovtsians.

1113 - an uprising in Kiev against the usurers. The vocation of Vladimir II Vsevolodovich Monomakh to reign in Kiev.

1113-1125 - the great reign of Vladimir II Vsevolodovich Monomakh in Kiev. The publication of the "Charter of Vladimir Monomakh", which limited usury.

1116 - the victory of Prince Vladimir Monomakh over the Polovtsy.

1125-1132 - the great reign of Mstislav Vladimirovich in Kiev.

Boleslav I the Brave - Polish prince (992-1025, king in 1025) from the Piast dynasty. At the beginning of his reign, he maintained friendly relations with the Kiev prince Vladimir I Svyatoslavich, which allowed him to defend the western borders and create a strong state. However, he later intervened in the internecine struggle in Russia. In 1018 Boleslav I made a campaign against Kiev, supporting Svyatopolk against Yaroslav the Wise. Interference in the affairs of the Kiev state weakened Poland and led to setbacks in foreign policy (in 1021 the Czech Republic regained Moravia).

Boleslav II the Bold - Polish prince (1058-1079, from 1077 king) from the Piast dynasty. He intervened in the internal struggle in Kievan Rus. He made two campaigns to Kiev (1069, 1077) under the pretext of providing military assistance to his son-in-law, the Kiev prince Izyaslav, in the return of the Kiev throne. In 1069 he occupied the city, but was expelled by the Kievites. Boleslav's interference in Russian affairs diverted his attention from the western border, where Poland at that time suffered serious losses (lost Western Pomerania). As a result of the uprising of large landowners who were dissatisfied with his policy, he was forced to flee the country.

Boris II - Bulgarian tsar (969-972). During his reign, Bulgaria was subjected to the military onslaught of Byzantium and Rus. The great Kiev prince Svyatoslav in 969 occupied the capital of Bulgaria (Veliky Preslav), but retained the throne for Boris and, having entered into an alliance with him, waged war with Byzantium (969-971). After the conclusion of the Russian-Byzantine peace treaty in 971, Byzantine troops defeated Bulgaria and annexed it to the possessions of the empire. Boris was stripped of the throne, declared a master and sent to Constantinople.

Boris (Christian name Roman) (until 988-1015) - Prince of Rostov, son of Prince Vladimir I from the Byzantine princess Anna, elder brother of Gleb. Having learned about the seizure of the grand-ducal table by Prince Svyatopolk, his half-brother, he refused to fight with him. He was killed by supporters of Svyatopolk I and canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church. The details of these events were reflected in two literary monuments of the 11th century. - "Reading about the life and the destruction of Boris and Gleb" and "Legend and passion and praise to the holy martyrs Boris and Gleb."

Basil II of the Bulgar fighter - Byzantine emperor (976-1025). He led a difficult struggle with the landowners of Western Bulgaria. To suppress the rebellion (987-989), he entered into a military alliance with the Kiev prince Vladimir I. Under the terms of the agreement, the emperor's sister, Princess Anna, was married to Vladimir I, and the prince himself converted to Christianity and baptized Russia according to the Byzantine model.

Saint Vladimir I (Christian name Vasily) - Prince of Novgorod from 969, Grand Duke of Kiev (980-1015). The youngest son of Prince Svyatoslav and the housekeeper of Princess Olga Malusha. Conquered Vyatichi, Radimichi, Yatvyagi. He successfully fought with the Pechenegs, Volga-Kama Bulgaria, Poland, Byzantium. Under him, several defensive lines were built along the Desna, Sturgeon, Trubezh and Sule rivers, protecting Russia from nomads. In 988 he adopted Christianity and introduced it into the state, strengthening the internal and international position of Kievan Rus. The time of his reign was the heyday of Kievan Rus, sung in epics and literary works. He entered the Old Russian epic with the name "Saint", "Red Sun". Canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church as an Equal-to-the-Apostles saint.

Vladimir II Monomakh - Prince of Smolensk (from 1067), Chernigov from (1078), Pereyaslavl (from 1093), the Great Prince of Kiev (1113-1125). The son of Vsevolod Yaroslavich and the Byzantine princess Maria from the Monomakh house. He fought the internecine strife of the princes and strengthened the unity of the Russian lands. He successfully fought with the Polovtsy, organizing joint princely campaigns against them (1103, 1107, 1111, 1113). In 1113, after the uprising in Kiev, he issued the "Ustav", which limited the arbitrariness of the usurers and eased the procurement situation. The author of "Instructions" to his sons, in which he summarized his own life experience, called upon the princes to "end strife", observe the principle of succession to the throne by seniority in the family and follow the norms of Christian morality.

Vseslav Bryachislavich - Prince of Polotsk (1044-1101). In 1066, with the capture of Novgorod, he began an internecine war with the Yaroslavich brothers. In 1067 in the battle on the river Nemiga he was defeated and taken prisoner. In 1068, during the uprising in Kiev, he was proclaimed the Grand Duke, but after 7 months he was removed by Izyaslav. He enjoyed the sympathy of the people, entered the epic epic as "Vseslav the Sorcerer." The Principality of Polotsk reached its heyday under him.

Vsevolod Yaroslavich - Prince of Pereyaslavl (from 1054), Chernigov (from 1076), Grand Duke of Kiev (1078-1093). Son of Yaroslav the Wise. His first marriage was married to the daughter of the Byzantine emperor Constantine IX Monomakh. Together with the brothers Izyaslav and Vsevolod, he fought against the Polovtsians, participated in the compilation of "Pravda Yaroslavichi".

Gleb - Prince of Murom (994 or 996-1015), son of Prince Vladimir I and the Byzantine princess Anna, younger brother of Boris. Killed by order of Svyatopolk I near Smolensk. Together with Boris, he was canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church. Princes Boris and Gleb became the first saints in Russia.

Dobrynya - educator and voivode, Prince Vladimir I, brother of the mother of Prince Malusha. He supported Vladimir I in the struggle for the Kiev table, participated in campaigns against Polotsk and Kiev (980), was the prince's governor in Novgorod, where he forcibly implanted Christianity.

Igor Stary - Kiev prince (912-945). According to the "Tale of Bygone Years" - the son of Rurik, in whose childhood Oleg ruled. According to other chronicles - the founder of the dynasty of Kiev princes, not associated with Rurik. In 915 he fought with the Pechenegs. In 941, 944. went on campaigns to Byzantium and concluded a treaty of peace and trade with it. In 945 he was killed by the insurgent Drevlyans, who resisted the prince's arbitrariness in collecting tribute.

Izyaslav is a Polotsk prince (988-1001), the son of the great Kiev prince Vladimir I and the Polotsk princess Rogneda Rogvolodovna. He was sent by Vladimir I to reign in the Polotsk land. The town of Izyaslavl (modern Zaslavl), which was rebuilt for him, became his residence. He became the founder of the Polotsk princely dynasty of the Izyaslavichi (Rogvolodovichi), who were in opposition to the Kiev princes. He laid the foundation for the political independence of the Polotsk principality. Under him Christianity spread in Polotsk, the Polotsk bishopric was established (991-992).

Izyaslav Yaroslavich - Grand Duke of Kiev (1054-1068, 1069-1073). In 1068 he lost the battle on the Alta River with the Polovtsy, after which he was expelled by the rebellious Kievites and sought salvation from his father-in-law, the Polish king Boleslav I. With his help, he restored his power in Kiev. In 1073 he was overthrown from the throne by brothers - Svyatoslav and Vsevolod. Participated in the compilation of "Pravda Yaroslavichi".

Hilarion - the first Kiev metropolitan from the Russian clergy (since 1051), earlier - a presbyter at the church in the princely village of Berestovo near Kiev. His approval by the metropolitan was associated with an attempt to free himself from the guardianship of Byzantium in church affairs. After the death of Prince Yaroslav the Wise (1054), he was removed from the post of head of the Russian Orthodox Church. Known as a writer, author of "The Word of Law and Grace" - a church-political treatise that glorified Kievan Rus and its princes - Vladimir I and Yaroslav the Wise. He was an active supporter of the independence of the Russian Church from Constantinople.

John I of Tzimiskes - Byzantine emperor (969-976). He fought a tense war with Kievan Rus, during which he managed to oust the Kiev prince Svyatoslav from the Balkan Peninsula and annex Danube Bulgaria to the empire (971).

Clement Smolyatich, Klim Smolyatich - Metropolitan of Kiev (from 1147), presumably from Smolensk. He was appointed metropolitan by the Kiev prince Izyaslav Mstislavich without the sanction of the Patriarch of Constantinople. After the death of the prince (1154), he was forced to leave the metropolitan see. He advocated the independence of the Russian Church from Byzantium. He was a highly educated person, an outstanding church writer. Only one of his works has survived - "The Epistle to the Smolensk Presbyter Thomas."

Konchak - Polovtsian Khan of the second half of the 12th century. He created a powerful union of the Polovtsian tribes. In 1172, 1180. supported the Seversk princes in their struggle with other principalities. He made a number of campaigns to the Pereyaslavl land (1174, 1178, 1183). In 1185 he defeated the squad of the Novgorod-Seversk prince Igor Svyatoslavich on the Kajala River and took him prisoner. In the same year and in 1187, Konchak's hordes attacked the Kiev and Chernigov lands. The struggle of the Russian princes with Konchak became the plot of the famous "Lay of Igor's Campaign."

Mal is a Drevlyan prince. In 945 he led a popular uprising against the Kiev prince Igor, caused by excessive extortions. After the murder of Igor, fearing retribution, he wooed his widow, Princess Olga. According to the chronicles, he died during the defeat of the Drevlyans by the army of Olga and the capture of Iskorosten, the main city of the Drevlyans.

Malusha was a slave, housekeeper of Princess Olga, a concubine of Prince Svyatoslav and mother of Vladimir I, who was often reproached with plebeian origin.

Mstislav Vladimirovich - Grand Duke of Kiev (1125-1132), son of Vladimir Monomakh. From 1088 he reigned in Novgorod, Rostov, Smolensk and others. He continued his father's policy, participated in princely congresses, successfully defended the Russian lands from the Polovtsians, and suppressed civil strife.

Oleg is a Varangian, governor of Rurik, the great Kiev prince (882-912). After the death of Rurik in 879 he began to reign in Novgorod. In 882 he undertook a campaign against Kiev, captured it and made it the capital of Russia. In 883-885 conquered Drevlyans, northerners, Radimichs. He fought successfully with the Khazars. In 907 and 911. (according to chronicle data) made campaigns to Byzantium, concluded a treaty that was extremely beneficial for Russia. The chronicler, based on oral tradition, calls him "Prophetic" and gives a story about the death of the prince, predicted by the sorcerer.

Oleg Svyatoslavich, "Gorislavich" - Prince of Vladimir-Volyn (1073-1076), Tmutarakansky (1083-1094), Chernigov (1094-1096), Novgorod-Seversky (1097-1115). Grandson of Yaroslav the Wise. In 1073 he received Rostov-Suzdal land from his father, then reigned in Volyn. After the death of his father (1076) he was in Kiev, where his uncle Vsevolod Yaroslavich sat on the throne. In 1078 he fled to Tmutarakan and with the help of the Polovtsy captured Chernigov. In a battle with the combined army of Izyaslav and Vsevolod Yaroslavich, he was defeated and again fled to Tmutarakan. In 1094 he brought the Polovtsian hordes to Russia, captured Chernigov and entered into a long struggle for Kiev with Svyatopolk Izyaslavich and Vladimir Monomakh. Oleg's alliance with the Polovtsy and his numerous "sedition" caused condemnation of the chronicler and gave the author of the "Lay of Igor's Host" to call him "Gorislavich".

Olga - princess of Kiev (945-969), wife of Prince Igor, mother of Prince Svyatoslav. Brutally suppressed the uprising of the Drevlyans (945). Rules in the early childhood of the son and during his campaigns. Has streamlined the collection of tribute in the state. She traveled to Constantinople (about 957), where she converted to Christianity.

Rogvolod is the first historically reliable Polotsk prince (? -980). He fought against the Kiev prince Vladimir Svyatoslavich. In 980, after the capture of Polotsk, Vladimir was killed along with his wife and two sons. His daughter Rogneda became Vladimir's concubine.

Rogneda - Princess of Polotsk, daughter of Prince Rogvolod (? -1000). Being the bride of the Kiev prince Yaropolk, she refused the matchmakers of Vladimir Svyatoslavich, the future Vladimir I. After the capture of Polotsk by Vladimir (980) and the murder of her father and brothers, she became the wife of Vladimir under duress and received the Slavic name of Gorislav. She tried to organize a conspiracy against him, avenging the death of her father and brothers. Mother of Izyaslav Vladimirovich, the founder of the Polotsk branch of the Rurikovichs, and Yaroslav the Wise. According to legend, after the baptism of Vladimir and the liquidation of his harem, she refused to use his permission to remarry and tonsured a nun under the name of Anastasia.

Sveneld, a Varangian, governor of Prince Igor, enjoyed the right to collect tribute from the Drevlyans. Participated in the conquest of the street, in the wars with Byzantium (941, 944). He also served Svyatoslav Igorevich, participated in campaigns against Byzantium and the Transcaucasus. He was the closest adviser to Yaropolk Svyatoslavich. He died after 977.

Svyatopolk I Damned - Prince of Turov (from 988), Kiev (1015-1019). The son of Yaropolk, adopted by Vladimir I. After his death, he took the Kiev table. In an effort to keep him, he began an internecine war in which he killed three of his five brothers: Boris of Rostov, Gleb of Murom, Svyatoslav the Drevlyansky and took possession of their inheritance. In 1017 he was expelled from Kiev by Yaroslav the Wise, but in 1018, with the help of the Polish king Boleslav I, he again seized the grand-ducal power. In alliance with the Pechenegs, he fought with Yaroslav the Wise, but in 1019 he was defeated by him on the Alta River and finally lost the great reign.

Svyatopolk II - Prince of Polotsk (1069-1071), Novgorod (1078-1088), Turov (1088-1093), Grand Duke of Kiev (1093-1113). He was distinguished by cruelty and greed. During his reign, civil strife continued, social conflicts intensified, caused by the growth of usury and the ruin of the trade and artisan population. The policy of Svyatopolk was the cause of the popular uprising in Kiev (1113).

Svyatoslav I - Grand Duke of Kiev (about 945-972), son of Prince Igor and Olga. Known as a talented military leader. From 964 he made campaigns to the Oka, the Volga region, the North Caucasus and the Balkans. Subdued the Vyatichi, freeing them from the rule of the Khazars, in 965. defeated the Khazar Kaganate, in 967 he fought with Danube Bulgaria. In 969-970. in alliance with her, he fought a war against Byzantium and in 971 concluded a peace treaty with her. In 972, on the Dnieper rapids, his army was defeated by the Pechenegs, and Svyatoslav himself was killed.

Svyatoslav II - Prince of Chernigov (from 1054), Grand Duke of Kiev (1073-1076). Son of Yaroslav the Wise. Together with the brothers, he participated in the further development of legislation. During the dynastic struggle, together with his brother Vsevolod, he expelled Izyaslav Yaroslavich from Kiev. He successfully defended the southern borders of Rus from the Polovtsians.

Tugorkan is a Polovtsian khan who united the Dnieper hordes. He raided and plundered the southern outskirts of the Old Russian state, reaching Kiev. He gave his daughter in marriage to the Kiev prince Svyatoslav Izyaslavich.

Sharukan - Polovtsian Khan, head of the Sharukanid tribal association. He made predatory raids on Russian lands. He was defeated by the Kiev princes Svyatoslav Yaroslavich (1068) and Vladimir Monomakh (1106 and 1111).

Jan Vyshatich - Kiev thousand, a prominent representative of the nobility. The son of Vyshata, the governor of Prince Yaroslav the Wise, who participated in the campaign of the Russian squads against Byzantium in 1043. Apparently, he inherited the position of the Kiev tysyatskiy from his father. Under Prince Izyaslav Yaroslavich he was the first among the Kiev boyars. In the 70s. traveled to Beloozero, where he brutally suppressed the uprising of the smerds. In 1093 and 1106. participated in campaigns against the Polovtsians. His stories about these events were used in the Kiev chronicle. He died in 1106.

Yaropolk I - Prince of Kiev (972-980), the eldest son of Prince Svyatoslav I. One of the first in Kiev to accept Christianity. In 977, in an internecine quarrel, he killed his brother, the Drevlyan prince Oleg, but in 980 he was defeated by Vladimir.

Yaroslav the Wise - Grand Duke of Kiev (1019-1054), son of Vladimir I. He took part in the struggle for the Grand Duke's throne after the death of his father. Expelled from Kiev Svyatopolk I. He made a number of successful campaigns against the Pechenegs, secured the western borders of Russia. During the years of his reign, Kievan Rus reached its heyday: churches and cities were built, international relations (including dynastic ones) with many European countries expanded. The compilation of the first all-Russian legislation - "Russian Pravda" is associated with the name of Yaroslav.

Alta (Lto, Olta) is the name of the river flowing into Trubezh, and its tract to the southeast of Kiev. According to the chronicle, in this area, during the dynastic struggle that began after the death of Grand Duke Vladimir I between his sons, Boris was killed by order of Svyatopolk in 1015. In 1018 Yaroslav on the Alta defeated the combined waxes of Svyatopolk and the Pechenegs. In 1068, a battle took place here between the troops of the Yaroslavich princes (Izyaslav, Svyatoslav, Vsevolod) and the Polovtsy, in which the brothers were defeated and fled. These events sparked a popular uprising in Kiev.

Boyars - in ancient Russia, a privileged part of society, landowners, “princes, men and vassals of the prince. The boyars were formed from the descendants of the tribal nobility and the upper layer of the princely squad. They had their vassals, enjoyed the right of feudal immunity. They made up a council under the prince - the Boyar Duma.

A vassal is a servant, a feudal lord who received from a seigneur (a larger feudal lord) land ownership (feud, patrimony) for serving, mainly military, and occupied a dependent position.

Vassalage (vassal-fief system) - a system of relations of subordination of feudal vassals to feudal lords. Begins to form in ancient Russia at the end of the XI - the beginning of the XII century.

Veche is a national assembly in ancient Russia. It was most active in the second half of the 11th-12th centuries. It consisted of boyars, church hierarchs, merchants, townspeople or rural residents. Veche resolved issues of war and peace, legislation, summoned princes, concluding a "row" with them, and expelled them if the conditions of the "row" were not met. Rooted in the tribal system and the era of military democracy, the veche was the main body of people's participation in government.

Eternal people, eternal boyars (eternal) - participants in veche meetings.

Byzantium - Eastern Roman Empire, Byzantine Empire (IV-XV centuries). It was formed during the collapse of the Roman Empire in its eastern part (Balkan Peninsula, Asia Minor, southeastern Mediterranean). The capital is Constantinople (Constantinople). It achieved the greatest territorial expansion under Emperor Justinian I, becoming a powerful Mediterranean power. Conducted an active trade with Scandinavia and Kievan Rus. It was repeatedly attacked by the Kiev princes (in 860, 907, 911, 944, 970), who defended the military and commercial interests of Russia in the Black Sea region. In 980, with the participation of Byzantium, Russia adopted Christianity.

Vira is a fine for the murder of a free person in Kievan Rus. Taking vire replaced the custom of blood feud.

Virnik is a representative of the princely or boyar administration, the "prince husband", who collected court fines (vir).

Volga Bulgaria (Volga-Kama Bulgaria) is the first state formation of the peoples of the Middle Volga and Kama regions, formed in the 10th century. in the fight against the Khazars. After the defeat of the Khazar Kaganate by the Kiev prince Svyatoslav (965), she finally freed herself from the power of the Khazars. The capital is the city of Bulgar. It was located on important trade routes connecting Eastern Europe with the East and actively traded with the Arab Caliphate, Byzantium, and Russia. In 1066 a Russian-Bulgar trade agreement was concluded. The Kiev princes made several campaigns against the Volga Bulgaria (977, 985, 994, 997). Since the XI century. its main rival was Vladimir-Suzdal Rus, which caused military conflicts and entailed the transfer of the capital to the city of Bilyar. In 1241 it was subdued by the Mongols and became part of the Golden Horde.

Bulgars are Turkic tribes. They united into an alliance, which in the VII century. divided into several groups. Part of them wandered in the Azov region and in the North Caucasus. Another group penetrated the Balkans, where it merged with the local Slavic population. The third settled in the Middle Volga region, subjugated a number of Finno-Ugric tribes and headed the multi-ethnic state formation - the Volga-Kama Bulgaria.

Volost is an administrative-territorial unit in ancient Russia. Sometimes it coincided with the borders of the land or principality, sometimes it was only a part. Subordinated to the city as an administrative and political center. The term is also used in the meaning of a semi-independent inheritance ruled by the princes-vassals of the Kiev ruler.

Volostel was an official in Russia in the XI-XVI centuries, who ruled the volost on behalf of the grand or appanage prince and was in charge of administrative and judicial affairs. Not receiving a salary from the government, he “fed” at the expense of the taxable population of the volost, taking “feed” in the form of natural products and various duties. Auxiliary staff with him were tiuns, closers, righteous ones. His power in the immunity domain was limited to letters of gratitude.

Magi, sorcerers, "blasphemers" - priests, pagan worshipers among the Eastern Slavs. They belonged to the top of society. The Magi were credited with influencing the forces of nature, curing diseases, predicting the future. They are first mentioned in the annals under 912 in connection with the prediction of death to Prince Oleg. After the adoption of Christianity, they led the anti-church opposition and were persecuted by the state and the church. In the XI century. repeatedly led popular uprisings (in the Suzdal land, Kiev, Beloozero).

Patrimony is a type of feudal landed property. In ancient Russia, it arose at the end of the X-XI century. by way of a princely grant, the seizure of communal peasant lands, or the allocation of wealthy peasants' possessions from the commune. Known princely, boyar, monastic estates. The owner of the patrimony could inherit it, sell it, mortgage it, etc. The term comes from the word “fatherland”, that is, the father's property.

The hryvnia is a monetary unit in Kievan Rus. In the XI century. was approximately 49, 25 g of silver.

Grid, gridin, griden - the prince's junior guard, the prince's bodyguard. Greedy made up the main personnel of the princely squads, participated in the management of the princely economy, lived at the prince's court in special premises - gridnits.

Tribute is a tax in kind or in cash. In ancient Russia, it was a form of dependence of tribes defeated or voluntarily submitted to the Kiev princes. The collection of tribute was carried out in the form of a polyudya. The right to collect was received by princely governors, noble warriors as payment for their service. Thus, the right to tribute was implemented by vassal relations in ancient Russia. The regulation and ordering of the collection of tribute was first carried out by Princess Olga in 947 during her campaigns in the Drevlyansk and Novgorod lands. The norms for collecting tribute were fixed in the "Statutes" of Princess Olga - collections of legal norms.

Tithing is a tenth of all income of tributes (fines) allocated by the prince for the organization and maintenance of the church. It was founded by Vladimir I simultaneously with the introduction of Christianity. It was levied from the population in the amount of a tenth of the harvest or other income.

Druzhina - an armed detachment under the prince, his closest circle, a privileged stratum of society. The squad was the basis, the core of the military forces of ancient Russia and at the same time participated in political administration, being a member of the council under the prince - the duma. The druzhinniki also managed the prince's personal household. The squad was divided into “senior” (“princes men”, “deliberate men”) and “young” (“greedy”, “youths”, “children”). The social position of the "senior" and "young" vigilantes was different.

Purchases - a category of a feudal-dependent population; persons who have taken a compartment and are obliged to work it out on the lender's farm with their own inventory. "Russkaya Pravda" distinguishes between "role" purchases (working on arable land) and cattlemen. When trying to escape, the purchase turned into a slave. The legal status of procurement is determined by the "Procurement Charter" issued by Vladimir Monomakh in 1113.

Outcasts are persons expelled or out of their social environment: peasants who have gone bankrupt and have left the community; freedmen or ransomed slaves ("puschenniki" and "forgiven"), princes expelled from their inheritance and bereft of inheritance. Urban and rural are well known.

Immunity - the right of the landowner to exercise some of the functions inherent in the central government (court, collection of taxes, etc.) in their possessions. Denied access to the princely administration in the possession of the boyars and monasteries. It was given by the Grand Duke of Kiev, and then to Vladimir's large secular and spiritual estates and was issued with special letters.

Kajala is a river mentioned in the "Lay of Igor's Regiment" as the place of defeat of the Russian troops led by the Novgorod-Seversk prince Igor Svyatoslavich from the Polovtsians in 1185. Which of the Azov rivers carried in the XII century. this name is not precisely established. Some researchers suggest Kalka in it, others - Kagalnik, Dry and Wet Yaly, Kalmius.

Kievan Rus is an early feudal state that arose on the lands of the Eastern Slavs in the 9th century. (in the eastern, Byzantine sources and the Bertinian annals - the kaganate). The conditional date of its formation is considered to be 882, when the Novgorod prince Oleg united Novgorod and Kiev - two centers of ancient Russian statehood. It flourished at the end of the 10th - 11th centuries. under the princes Vladimir I and Yaroslav the Wise. In the second half of the XI century. the princely feuds and the raids of the Polovtsians led to the weakening of the state. In the second quarter of the XII century. Kievan Rus entered the final phase of disintegration into separate principalities and lands.

Kuna is a monetary unit of ancient Russia, in the XI century. was approximately 1.97 g. of silver.

Kupa is a loan provided by a landowner to a peasant-smerd in the form of a sum of money, grain, etc. at interest.

A catcher is a place for fur hunting or fishing, where part of the tribute was collected in furs or fish.

Lyubech congress - congress of Russian princes (1097) in the city of Lyubech on the Dnieper, which was attended by 6 princes (Svyatopolk Izyaslavich of Kiev, Oleg and David Svyatoslavich, Vladimir Monomakh, David Igorevich Volynsky, Vasilko Rostislavovich). The congress was prompted by the need to organize a joint struggle against the Polovtsians in the conditions of the beginning of the specific fragmentation of Russia. The princes made peace with each other and decided not to allow internecine strife in the future. The most important resolution of the congress was expressed in the formula: "kozhd keep his patrimony", which officially recognized the existence of principalities independent from each other, which were hereditary possessions. However, the decision of the congress not only did not end the princely strife, but also unleashed a new internecine war, the reason for which was the blinding of the Terebovl prince Vasilko by the Kiev prince Svyatopolk Izyaslavich and the Volyn prince David Igorevich.

Metropolitan is one of the highest ecclesiastical dignities, subordinate directly to the patriarch. The Metropolitanate of Kiev, established in 888, was part of the Constantinople Patriarchate. The first metropolitan of Kiev was Anastas Korsunsky. In ancient Russia, the metropolitan throne was usually occupied by the Greeks, twice - by the Russians: Hilarion (1051) and Clement (1147).

Nogata is a small currency in ancient Russia. In the XI century. was approximately 2, 46 g. of silver.

Nomokanon is a collection of norms of ecclesiastical law of the Orthodox Church, containing the rules of the internal order, everyday life, family life. It included the decrees of the Ecumenical Councils, the laws of the Byzantine emperors on church issues, etc. From the 9th century. Nomokanon began to be translated into Slavic languages. In Russia, it was revised and supplemented taking into account local conditions and received the name of the Kormchai book.

Ognischanin - a term derived from "fire" (hearth), "prince husband", boyar, managing the prince's patrimony. Boyars-firemen were part of the "senior" squad of the prince, owned land and enjoyed privileges. Ognischans, perhaps, were in charge of the palaces of the princes in the cities as well. The princely warriors who performed administrative functions were also called firemen. These persons were under the special protection of the law. The murder of a fireman was punishable by a fine of 80 hryvnia. In the Novgorod land, firemen were called medium and small landowners, owners of the subsection ("fire").

The Pechenegs are a union of Turkic and other nomadic pastoral tribes in the 8th-9th centuries. in the Trans-Volga regions, in the 9th century. - in the southern Russian steppes. They made predatory raids on Russia. In 1036 they were defeated by Prince Yaroslav the Wise, after which the tribal union collapsed.

Pogost is a term widespread in sources, having during the X-XVI centuries. different meaning. In its original meaning, rural communities on the periphery of Kievan Rus, as well as the centers of these communities, where "guest" (trade) was conducted, were called a graveyard. Gradually, this name in the Kiev state spread to administrative units consisting of numerous villages, as well as their centers. At the head of the graveyards were appointed special officials responsible for the regular flow of tribute. With the spread of Christianity in Russia, churches were usually built in graveyards, near which there were cemeteries. The sizes of the graveyards were different: from several dozen to hundreds of villages.

Entrance (entrance prince) - a princely or boyar administrator who traveled around the land and collected taxes.

Polovtsy (Kipchaks, Kumans) - Turkic people, nomads (in the 10th century - on the territory of Kazakhstan). In the 11th century, advancing in the steppes of the Northern Black Sea region, they drove out the Pechenegs. Since 1055 they made devastating raids on Russia. In 1103-1116. the attacks stopped as a result of the joint campaigns of the Russian princes, but resumed in the second half of the 12th century. In the XIII century. the Polovtsians were defeated and conquered by the Mongol conquerors. Partially moved to neighboring lands.

Polyudye is a form of collecting non-fixed tribute. A detour by the prince or his governor with the squad of the subject lands.

Posadnik - the governor of the prince in the lands of Kievan Rus in the X-XI centuries.

Forgiven - a category of dependent population in ancient Russia, are mentioned in the monuments of church law. In the opinion of most researchers, these are former slaves who were freed to work on church lands, as well as people who became dependent on the church after the “forgiveness” (healing) of their illnesses.

Puschenniki - a category of dependent population in ancient Russia, are mentioned in the charter of the Novgorod prince Vsevolod Mstislavich at the place where the term "forgiven" is used in other monuments. In later sources this term is used in the meaning of "freedmen".

Warriors, military men, warriors - the people's militia in ancient Russia, called so, in contrast to the warriors - the constant army of princes and boyars. Warriors were recruited for the duration of wars and campaigns from the urban population and peasants.

Rezana is a small currency in ancient Russia. In the XI century. was approximately 0.98 g of silver.

"Russkaya Pravda" is a set of laws of ancient Russian society, the most important source on the socio-economic history of Kievan Rus and the Russian principalities of the period of fragmentation. It was compiled during the XI-XII centuries. Known in over 100 copies. According to its content, it is divided into 3 editions: "Short", "Extensive" and "Abridged". "Brief Pravda" consists of "Pravda Yaroslav", "Pravda (" Statute ") of the Yaroslavichs", "Pocon (law) of the virgin", "Lesson to the bridge workers". “Extensive Pravda” is divided into “Court Yaroslavl Vladimirovich”, “Pravda Ruska” and “Charter Volodymer Vsevolodich”. "The Abridged Truth" does not contain new sections and is a variant of the "Extensive" one. "Russkaya Pravda" regulated legal relations in ancient Russia, protecting the life and property of various strata of ancient Russian society.

A number is a contract, an agreement that has legal force. In ancient Russia, he regulated relations between princes, as well as between various categories of the population.

Ryadovichi - persons who were hired to serve the landowner under a "row" (agreement). They occupied minor administrative positions in boyar or princely estates.

Senior - 1. Large land owner, owner of a senior (patrimony). As a feudal owner, he had subordinate peasants, as well as townspeople who lived on the territory of the seigneur. 2. In the vassal system, the lord of a group of vassals. The supreme lord of the territory (king, prince) was called the overlord. Secular and spiritual lords were distinguished.

Smerdy - communal peasants in ancient Russia. Initially free, with the development of feudal vassalage and the seizure of communal lands, they fell into economic dependence on the princes and boyars.

The Council is an advisory body under the Grand Duke of Kiev (Duma). It consisted of "Duma members": "princes, men", boyars, higher clergy (in peacetime), and during the war - the leaders of the allies. The council was in charge of issues of legislation, relations with the church, foreign policy.

Stanovishche is the administrative center, the seat of officials and the collection of princely fees.

The old child is the clan elders, the tribal nobility, who joined the social structure of Kievan Rus and formed part of the ruling class. Played a prominent role in local governance.

The headman - in ancient Russia, a representative of the lower princely or boyar administration, usually from serfs. In "Russkaya Pravda" village and military headmen are mentioned. The village headman, apparently, was in charge of the rural population of the estate and was the executor of the orders of the higher administration. Ratayny was in charge of the patrimonial arable land.

The Congress of Princes is an organ of political administration in Kievan Rus, a meeting in which the great Kiev and appanage princes took part. The congress resolved issues of a national character: the protection of the Russian land from external enemies, regulated relations between princes, and discussed the internal structure of Rus. The most significant all-Russian congresses are Lyubech (1097) and Dolobsky (1103).

Tiun is a princely or boyar servant who manages various branches of the economy. Minor administrative position in the fiefdom. Known tiuns: fire (in charge of the house, "fire", yard); stable boy (in charge of stables and herds); rural (managed villages); warrior - by arable work, etc. Most of the tiuns were not free people, if the free state was not stipulated by the terms of the contract (row).

Tmutarakan is an ancient Russian city of the X-XII centuries. on the Taman Peninsula. Played a large role in trade relations between Russia and the East. Until the X century. was ruled by the Khazars. After the defeat of the Khazar Kaganate (end of the 10th century), it became part of the Kiev state as the capital of the Tmutarakan principality. During the feudal dynastic struggle (mid-11th century), it was a stronghold of separatist-minded princes. At the beginning of the XII century. in connection with the strengthening of the onslaught of Byzantium and the Polovtsy, it was cut off from other lands of Russia and ceased to exist.

Tysyatsky - a military leader who led the ancient Russian city militia ("thousand"). He was appointed by the prince from among the senior vigilantes, sometimes by agreement with the city veche.

Lesson - a decree that determined the norms of tribute, fines, duties and other deductions in favor of the prince.

The charter is a collection of legal norms intended for the judiciary and the princely administration.

Serfs are a category of personally dependent population, close to slaves in their position. Initially, they did not have their own farm and performed various works for their owners. They consisted of a staff of domestic servants, artisans, patrimonial administration, and military squads of feudal lords were formed. Old Russian sources distinguish between two types of servitude: complete (white) and incomplete. They ended up in white slaves as a result of captivity, sale for debts, marriage with a slave or a servant "without a row." Incomplete servility was formalized by an agreement (nearby) with witnesses and was limited by its terms.

Chelyad (singular - chelyadin) - the general name of persons who served the princely or boyar house and economy: serfs, ryadovichi, purchases.

Black klobuki - a tribal association formed from the remnants of the Turkic nomadic tribes (Pechenegs, Torks, Berendeys), vassals of Russia, around the middle of the 12th century. Occupied forest-steppe regions (mainly along the Ros River). The creation of the association was largely due to the need for protection from the Polovtsians. As vassals of Russia, the black hoods were obliged to protect its southern borders, to participate in the campaigns of the Kiev princes against internal and external enemies. Under the influence of the neighboring sedentary population, they gradually switched from nomadic pastoralism to agriculture. In the XIII century. partially mixed with the Russian population, partially migrated to the steppe and ceased to be mentioned in sources.

The Tale of Bygone Years. In 2 volumes. M.; L., 1950.

True Russian. In 3 volumes. M.; L., 1940-1963.

The introduction of Christianity in Russia. M., 1987.

Vernadsky G.V. Kievan Rus. M., 1996

Gorsky A.A. Old Russian squad. M., 1989.

Grekov B.D.Kievan Rus. M., 1953.

Gumilev L. N. Ancient Russia and the Great Steppe. M., 1992.

History of Russian foreign policy. Late 15th - 17th century. M., 1990.

Kargalov V.V., Sakharov A.N. Generals of Ancient Russia. M., 1986.

Kuzmin A.G. The Fall of Perun. M., 1988.

Novoseltsev A.P., Pashuto V.T., Cherepnin L.V. The ancient Russian state and its international significance. M., 1965.

Pashuto V. T. Foreign policy of Ancient Russia. M., 1968.

Rapov O. M. Russian Church in the 9th - first third of the 12th century. The adoption of Christianity. M., 1988.

Sakharov A.N. Foreign policy of Ancient Russia. IX - first half of the X century. M., 1980.

Sverdlov M.B. Genesis and structure of feudal society in Ancient Russia. M., 1983.

Sedov V.V. The Slavs and the Early Middle Ages. M., 1995.

Tolochko A.P. Prince in Ancient Rus: power, property, ideology. Kiev, 1992.

Froyanov I. Ya. Ancient Russia. Experience in researching the history of social and political struggle. M .; SPb., 1995.

Froyanov I. Ya., Dvornichenko A. Yu. City-states of Ancient Rus. L., 1980.

The Great Steppe stretches almost from the Pacific Ocean in the East to the Danube in the West. For centuries, the Steppe served as the birthplace of nomadic hordes, destroying and conquering more civilized territories from China and Central Asia to Europe. Cimmerians, Scythians, Sarmatians, Goths, Huns, destroying and absorbing each other, swept along the northern Black Sea coast.

The first, with whom the young ancient Russian state had to face, were the Khazars. The Türkic union of tribes, possibly the descendants of the Huns, in the 7th century separated into its own state - the Khazar Kaganate. The Khazars collected tribute from the peoples inhabiting the Crimea, the Azov region and the North Caucasus. Over time, the Eastern Slavs also fell into the number of tributaries: glade, northerners, radimichi, vyatichi.

The appearance of the Varangians and the formation of the Old Russian state radically changed the situation in the region - the Russian princes, subjugating the Slavic tribes, faced the Khazars.

“In the year 6393 (885). Sent (Oleg) to the Radimichs, asking: "To whom are you giving tribute?" They answered: "Khazaram". And Oleg told them: "Don't give it to the Khazars, but pay me."

To protect themselves from the Russians, the Khazars erect a series of fortresses on their northwestern borders. To do this, they ask for help from Byzantium and receive it. The main fortress was the city of Sarkel on the left bank of the Don.

In 965 Svyatoslav Igorevich went to the Eastern campaign against the kaganate.

“In the year 6473 (965), Svyatoslav went to the Khazars ... Svyatoslav defeated the Khazars, and took their capital and Belaya Vezha. And he defeated the Yases and Kasogs ... "

Then Samkerts (Tmutarakan) was captured and the Tmutarakan principality was formed. In 968-969. Itil was taken and destroyed by Svyatoslav. The war ended with the destruction of the independent Khazar state. The leaders were forced to ask for help from Shirvan and Khorezm, to abandon Judaism in favor of Islam. But in 985, the prince made a campaign against Khazaria and imposed a tribute on it. Khazaria soon ceased to exist as a state. Later, the Khazars serve in the army of Mstislav Tmutarakansky. Many migrate to Crimea, Khazars who live in Kiev are mentioned.

Pechenegs

The Pechenegs were a union of Turkic-speaking, partly Sarmatian and Finno-Ugric nomadic tribes. They appeared in the Wild Field in the 8th century, squeezed out of Asia by stronger rivals. The Nikon Chronicle says so about the first clash of the Slavs with the Pechenegs:

"The same summer, many Pechenegs Oskold and Deer were killed"

It happened in 875. Since then, almost all Russian princes either fought with the Pechenegs, or enter into alliances with them. So in 944 the steppe inhabitants went on a campaign with Igor against the Byzantines. With Svyatoslav, the Pechenegs are fighting against Khazaria in 965 and Byzantium in 970. But during the prince's campaign against the Bulgarian kingdom, the Pechenegs besieged Kiev. They also lay in wait for Svyatoslav on the Dnieper rapids and took his life.

After the death of Svyatoslav, the nomads took advantage of the civil strife between his sons, raids became more frequent. In 922, a battle took place on the Trubezh River, which ended in the defeat of the Pechenegs. In honor of this victory, Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavich ordered the founding of the city of Pereyaslavl on the site of the battle.

In 995, the Pechenegs' raid was more successful, Vladimir was defeated and fled to Novgorod to gather new forces. At this time, the nomads plundered the border lands. A legend is connected with the siege of Belgorod. When the supply of food in the besieged city ran out, the defenders set out on a trick: they dug two wells and put buckets of oatmeal and honey in them. The Pechenezh "best men" invited to the negotiations were given a taste from the wells, convinced that the earth itself gives food, they even gave supplies for the journey. Affected Pechenegs lifted the siege.

Belgorod jelly. Illustration from the Radziwill Chronicle

In 1015-1019. Pechenegs are fighting on the side of the Kiev prince Svyatopolk the Damned and the Polish prince Boleslav the Brave against Yaroslav the Wise for the Kiev table. In 1019, in a decisive battle on the banks of the Alta River (Kiev region), the troops of the Pechenegs, Boleslav and Svyatopolk were defeated.

In 1036, the Pechenegs approached Kiev and laid siege to it. Yaroslav gathered an army of Novgorodians and Varangians in the Novgorod lands and utterly defeated the nomads. Most of them were destroyed during the flight. In honor of this victory, Yaroslav ordered to lay the Church of St. Sophia in Kiev. The damage suffered by the Pechenegs was so strong that after the battle of Kiev they never again invaded the Russian lands, and soon completely disappeared from the Wild Field.

Polovtsi

In the middle of the 11th century, the Steppe becomes Polovtsian - Desht-i-Kipchak. The Kipchak Cumans take control of the lands from the Danube to the Irtysh. Warlike nomads squeezed out or assimilated other steppe dwellers from the Wild Field. Until the appearance of the Mongol-Tatars in the 13th century, they became the main military threat from the southeast. In the Russian principalities, these two centuries are a time of turmoil and civil strife. The Polovtsi regularly take the side of one or another Russian prince in their wars for power.

In 1097, the Lyubech congress of princes stopped mutual feuds. And at the Dolobsky Congress in 1103, the princes united to confront the Polovtsian threat. In the same year, in the battle at Suteni (a river in the Zaporozhye region), a united army of Russian princes utterly defeated the Polovtsi, 20 khans were killed.

Eight years later, in the battle of Salnitsa (upper reaches of the Seversky Donets), the Russian army again defeats the Polovtsians.

“In the summer of 6620 (1111). Idosh on the Polovtsi Svyatopolk, Yaroslav, Vsevolod, Volodymyr, Svyatoslav, Yaropolk, Mstislav, Davyd Svyatoslavich with his son Rostislav, and Olgovich, Davyd Igorevich and doidosh the city of Osenev and Sugrov, take the Polovets and beat the Polovets

In this battle, the nomads had such a great numerical superiority that they surrounded the Russians, but could not withstand the blow and fled. The Polovtsi lost more than 10,000 people in the battle.

After these battles, the Polovtsians leave for the Caucasus for a long time, beyond the Volga and Don. In the Caucasus, they serve the Georgian king David the Builder. After the death of Vladimir Monomakh, the period of internecine struggle begins again and the Polovtsy, on the side of the Suzdal and Seversky princes, take part in the campaigns against Kiev in 1169 and 1203. Russia loses the Tmutarakan principality and Belaya Vezha. The unsuccessful campaign of the princes to the Don, described in the "Lay of Igor's Campaign", belongs to the same period.

Rusichi field is large

Barred with scarlet shields,

Seek honor for yourself, and glory for the prince.

The end of the confrontation was put by the invasion of the Mongol-Tatars

One might get the impression that the history of the relationship between Russia and the Steppe is an ongoing war. But this is not the case. Chronicles, for the most part, are descriptions of campaigns and battles. Besides wars, there was mutually beneficial trade and mutual cultural penetration. The Khazars lived in Kiev and served the Russian princes. It was the Khazars who persuaded Vladimir to accept Judaism when he chose the faith for Russia. The Pechenegs, in alliance with the Russians, fought against Byzantium, Bulgaria, and Khazaria. The Cumans, according to some versions, could be the southern branch of the Slavs. Many princes were married to the Polovtsian princesses, including the founder of Moscow, Yuri Vladimirovich (Dolgoruky). The steppe inhabitants, in turn, adopted Orthodoxy and merged with the southern principalities. It is the united Russian-Polovtsian army that opposes the Mongols in the battle on Kalka.

Literature:

- The Tale of Bygone Years.

- Radziwill Chronicle.

- Egorov V. L. "Russia and its southern neighbors in the X-XIII centuries." Domestic history, 1994, no. 6

"East" is as vague and relative a concept as "West". Each of the eastern neighbors of Russia was at a different cultural level, and each was endowed with its own specific features.

Ethnographically, most of the eastern peoples living in the vicinity of Russia were Turkic. In the Caucasus, as we know, the Ossetians were an Iranian element. The Russians had some relationship with the Iranians in Persia, at least from time to time. The Russians' knowledge of the Arab world was limited mainly to Christian elements in it, as, for example, in Syria. They were familiar with the peoples of the Far East - Mongols, Manchus and Chinese - insofar as these peoples interfered in Turkestan affairs. In Turkestan, for example, Russians could meet with Indians, at least occasionally.

From a religious and cultural point of view, a distinction should be made between the areas of paganism and Islam. The nomadic Turkic tribes in the south of Russia - the Pechenegs, Polovtsians and others - were pagans. In Kazakhstan and northern Turkestan, most of the Turks were originally pagan, but when they began to expand the area of their raids to the south, they came into contact with Muslims, and were quickly converted to Islam. The Volga Bulgars were the northernmost outpost of Islam during this period. Despite the fact that they were separated from the main core of the Islamic world by the pagan Turkic tribes, they managed to maintain close ties, both in trade and religion, with the Muslims of Khorezm and southern Turkestan.

It should be noted that politically, the Iranian element in Central Asia has been in decline since the end of the tenth century. The Iranian state under the rule of the Samanid dynasty, which flourished in the late ninth and tenth centuries, was overthrown by the Turks around 1000 BC.

Some of the former vassals of the Samanids have now created a new state in Afghanistan and Iran. Their dynasty is known as the Ghaznavids. The Ghaznavids also controlled the northwestern part of India. However, their state did not last long after being destroyed by the new Turkic horde of Seljuk (1040). The latter, under the rule of the Sultan Alp-Arslan (1063 - 1072), soon invaded Transcaucasia (see 6 above), and then launched an offensive westward against the Byzantine Empire. In the twelfth century, they already controlled most of Anatolia and spread southward as well, devastating Syria and Iraq. However, they recognized the spiritual authority of the Baghdad Caliphate over themselves. In Egypt, by that time, a separate Cairo Caliphate was formed, in which the ruling dynasty was known as the Fatimids. At the end of the twelfth century, Syria and Egypt were politically united by Saladin, famous for his successes in opposing the crusaders. In general, we can say that the Islamic zone to the east and southeast of Russia in the Kiev period formed a limit for the degree of familiarity between Russia and the East. However, outside this limit, the powerful peoples of Turkic, Mongolian and Manchu origin were in constant motion, fighting with each other. The dynamics of the history of the Far East led to the fact that some Far Eastern tribes from time to time fell into the Central Asian and Russian field of vision. So, around 1137, part of the Kitan people, driven out of northern China by the Jurchens, invaded Turkestan and established their power there, which lasted for about half a century, until the power of the Khorezm Empire grew. It is from the name "Kitan" (also known as kara-china) that the Russian name for China comes from. The next Far Eastern breakthrough to the west was the Mongol.

It seems that, apparently, the relations with the Islamic peoples were more beneficial for the Russians than with the pagan Turks. The Turkic tribes in the southern Russian steppes were typically nomadic, and although relations with them greatly enriched Russian folklore and folk art, one could not expect from them a serious contribution to Russian science and education. Unfortunately, the irreconcilable attitude of the Russian clergy to Islam, and vice versa, did not provide an opportunity for any serious intellectual contact between Russians and Muslims, although it could easily have been established on the lands of the Volga Bulgars or in Turkestan. They had only some intellectual connections with the Christians of Syria and Egypt. It was said that one of the Russian priests in the early Kiev period was a Syrian. It is also known that Syrian doctors practiced in Russia during the Kiev period. And, of course, through the medium of Byzantium, the Russians were familiar with Syrian religious literature and Syrian monasticism.

It may be added that along with the Greek Orthodox Christian Church in the Middle East and Central Asia there were also two other Christian churches - Monophysite and Nestorian, but the Russians undoubtedly avoided any relationship with them. On the other hand, some Nestorians, as well as some Monophysites, were interested in Russia, at least judging by the Syrian chronicle of Ab-ul-Faraj, nicknamed Bar Hebreus, which contains a certain amount of information about Russian affairs. It was written in the thirteenth century, but is based in part on the work of Michael, the Jacobite patriarch of Antioch in the twelfth century, and other Syrian material as well.

Commercial relations between Russia and the East were lively and beneficial for both. We know that in the late ninth and tenth centuries, Russian merchants visited Persia and even Baghdad. There is no direct evidence to indicate that they continued to travel there in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, but they probably visited Khorezm in this later period. The name of the Khorezm capital Gurganj (or Urganj) was known to Russian chroniclers who called it Ornach. Here the Russians must have met travelers and merchants from almost every eastern country, including India. Unfortunately, there are no records of Russian travels to Khorezm during this period. Speaking of India, Russians in the Kiev period had a rather vague idea of Hinduism. "Brahmanas are pious people" are mentioned in the Tale of Bygone Years. With regard to Egypt, Soloviev claims that Russian merchants visited Alexandria, but the credibility of the source of such evidence, which he used, is problematic.

Although private contacts through trade between the Russian and Volga Bulgars and the inhabitants of Khorezm were apparently lively, the difference in religions represented an almost insurmountable barrier to close social relations between citizens belonging to different religious groups. Marital relations between the followers of Greek Orthodoxy and Muslims were impossible, unless, of course, one of the parties expressed a willingness to renounce their religion. During this period, practically, there are no known cases of conversion to Islam by the Russians, with the exception of those Russian slaves who were transported by ships by Italian and eastern merchants to various eastern countries. In this respect, it was much easier for the Russians to have contacts with the Polovtsians, since the pagans were less attached to their religion than the Muslims, and did not object to the adoption of Christianity, if necessary, especially women. As a result, mixed marriages between Russian princes and Polovtsian princesses were frequent. Among the princes who entered into such alliances were such outstanding rulers as Svyatopolk II and Vladimir II of Kiev, Oleg of Chernigov, Yuri I of Suzdal and Kiev, Yaroslav of Suzdal and Mstislav the Brave.

Although, as we have just seen, religious isolation precluded the possibility of direct intellectual contact between Russians and Muslims, the situation was different in the field of art. In Russian decorative art, the influence of oriental designs (such as, for example, arabesques) is clearly traced, but, of course, some of these designs could have got to Russia not directly, but through contacts either with Byzantium or with Transcaucasia. However, as far as folklore is concerned, we must recognize the direct influence of Eastern folklore on Russian. As for the influence of Iranian epic poetry on Russian, Ossetian folklore was obviously its main conductor. Türkic patterns are also clearly revealed in Russian folklore, both in epics and in fairy tales. It has already been noted (see Ch. IX, 4) the striking similarity in the order of the scale of the Russian folk song with the songs of some Turkic tribes. Since many of these tribes were under the control of the Polovtsians, or were in close contact with them, the role of the latter in the development of Russian folk music was probably extremely important.

In summary, the Russian people throughout the Kiev period were in close and diverse contacts with their neighbors, both eastern and western. There is no doubt that these contacts were very beneficial for the Russian civilization, but they basically demonstrated the growth of the creative powers of the Russian people themselves.

For a long time the European East did not have a permanent population, only nomadic tribes sometimes moved from place to place, arranging temporary settlements. The settled tribes that formed over time were engaged in agriculture and were much richer than the nomads. Therefore, for many centuries, nomadic tribes from Asia raided Europe, considering robbery to be the easiest way to acquire life's benefits.

In the 5th century BC. the inhabitants of the southern steppe were Scythians-nomads, and to the north of them up the Dnieper lived the Scythians-plowmen subject to them.

Over time, the Sarmatians who lived in Asia entered Scythia and annexed its inhabitants to their people.

Another nomadic people, the Alans, lived between the Caspian and Black Seas. Alane drove the Sarmatians out of southeastern Russia.

In the 3rd century, the Goths, the people of the Germanic tribe, began to rage. In the IV century, in the southwestern part of our country, the Goths formed a strong state. Their king, Ermanarikh, also subjugated the Wends, who, according to some scholars, were the same tribesmen of the Slavs.

At the end of the 4th century, Asian nomads, the Huns, attacked the Alans, Goths and Roman possessions, as a result of which the great empire of the Goths was destroyed. History also mentions the Antes, who, together with the Wends, belonged to the Slavic people. The Antes and Wends recognized the power of the Huns over themselves. But with the death of their king Attila, the rule of the Huns also ceased.

In the 6th century, a new Asian people discovered their way to the Black Sea. The Avars united with other hordes of the same tribe and conquered all of southern Siberia. Ugrians, Bulgarians, Ants recognized the power of the Avar Khan Bayan. In 568 the region, conquered by the Avars, stretched from the Volga to the Elbe. Khan Bayan also achieved the conquest of the Slavs.

Finally, driven to despair, the Bohemian Slavs fought against the nomads, pacified the Avars and regained their independence. In the 7th-8th centuries, the Slavs advanced deep into the steppe, in a southeastern direction from the middle Dnieper region, occupying the Don, the mouth of the Southern Bug, Dniester, and Danube. At the beginning of the 7th century, having concluded an alliance with Constantinople, the Avars were expelled from there. The power of this Asian people has weakened.

The Khazars, a people of Turkish-Tatar origin, lived next to the eastern Slavs on the western side of the Caspian Sea. The Khazars traded with Asian peoples and Eastern Slavs, and some of them were forced to pay tribute to themselves. The Slavic tribes, without a fight, fell under the rule of the Khazar Kaganate, which arose in the 7th century in the North Caucasus. The yoke of these conquerors did not oppress the Slavs. The Khazars blocked access to them for the nomadic hordes, who were pushing from the east, and established peaceful relations with the Slavs. But a different attitude towards the Khazars was among the Polyans, Radimichs, Northerners, Vyatichi. They paid a considerable tribute, but the Khazars could not protect them from the attack of the Bulgarians. The Khazar Kaganate was destroyed by Prince Svyatoslav.

In the second half of the 9th century, a new wave of invasions by Asian nomads began, this time by the Pechenegs and Turkic tribes. In the late 8th - early 9th centuries, under pressure from the Guzes, the Pechenegs moved westward, captured the steppes between the Volga and the Urals, forming a powerful tribal union here. At the end of the 9th century, the Pechenezh horde pushed back the Ugrians (Hungarians), and by the beginning of the 10th century, it took possession of the entire steppe part of the Northern Black Sea region. The Pecheneg horde has become a serious threat to its neighbors. In 915, the Pechenegs, having concluded an alliance with Prince Igor, did not disturb Russia for five years. In 920, a battle took place between them, the outcome of which is unknown to history. After that, the Pechenegs disappear from history for 25 years.

Prince Svyatoslav had to repel the Pechenezh raids more than once. The hard war with the Pechenegs continued until the death of Prince Vladimir and, judging by the chronicle news, did not bring decisive successes to Russia.

Only Yaroslav managed to finally defeat the Pechenegs. The last fierce battle took place in 1036, in which the Pechenegs were defeated. The struggle against the Pechenegs lasted for several decades and was the main foreign policy task of Ancient Rus.

In 1054, near the Russian borders, the Pechenegs were replaced by torques (guzes). The forces of the Torks were small, and so that they would not enter into an alliance with the Polovtsy against Russia, the Yaroslavich brothers defeated them, eliminating the foreign policy problem.

In the middle of the 11th century, a terrible danger arose for Russia in the person of the Polovtsians, who captured the entire steppe zone from the Volga to the Danube. In the second half of the 11th century, large associations were formed among the Polovtsians, headed by khans. The first clash of Kievan Rus with the Polovtsy happened in 1061. Three years after this, strife begins between the Russian princes, the sons of Yaroslav. The division into appanages weakened the Russian land, which the enemies of the Slavs did not fail to take advantage of. Only in 1111, Vladimir Monomakh, managed to break the enemies. After this defeat, the Polovtsians did not disturb Russia for a long time.

The struggle against the nomadic Polovtsians lasted a century and a half. From 1061 to 1210, the Polovtsians made 46 large campaigns against Russia, not counting many small raids.

The Polovtsian nomads were defeated by the Mongol-Tatar conquerors who invaded the Black Sea steppes in 1222-1223. The Mongol-Tatar invasion was approaching Russia ...

In 1238, Khan Batu approached the borders of the ancient Russian state. Conquering one city after another, the entire territory of Kievan Rus was under his rule. Years of even more difficult and bloody struggle began.

The constant threat from the nomads managed to unite the forces of the Slavs in the struggle against the common enemy, which contributed to the formation of the mighty Old Russian state.

In the IX century. in the steppes, separate hordes of Pechenegs began to appear, coming from the banks of the Volga and the Urals. In the X century. the Pechenegs filled all the southern Russian steppes, reaching the Danube in the west. The settlement of the Slavic farmers on the steppe was suspended, the southeastern Slavic settlements on the Don, in the Azov and Black Sea regions were cut off from the main Russian lands, and Russia itself, on a vast thousand-verst area, came under the blow of the Pechenegs. In the middle of the X century. the Pechenegs managed to push back the Russian possessions to the north. Byzantium skillfully used this new force and often set the Pechenegs against the strengthened Old Russian state.

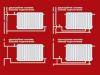

Construction of cities on the steppe outskirts of Russia

The government of Vladimir Svyatoslavich had to take energetic measures in order to protect Russia from the annual rapid and devastating raids of the Pechenezh khans, who took the Russian people prisoner and left behind the smoke of burnt villages and cities. Vladimir undertook the construction of cities on the southern steppe outskirts. To carry out garrison service in these new cities, the "best men" moved from the northern distant regions of Russia. So the feudal state managed to organize defense, attracting to

the fulfillment of the national tasks of the vigilantes of those Russian lands, who were not directly threatened by the raids of the Pechenegs.

The significance of the struggle against nomads was that it protected the agricultural culture from ruin and reduced the area of extensive nomadic farming in the fertile steppes, giving way to more perfect arable farming.

Black Bulgarians. Torquay. Berendei. Polovtsi

In addition to the Pechenegs, the Black Bulgarians (in the Azov region) and the Torks and Berendei (along the Ros River) lived in the southern Russian steppes. Russian princes sought to win them over to their side and use them as mercenary troops. The light cavalry of the Torks took part in the campaigns of the Russian princes.