State Polar Academy

St. Petersburg

Department of French Language and Literature

Faculty of Philology

Ferdinand de Saussure

Performed:

Strautman Anastasia

1st year student group 0221

Biography

Ferdinand de Saussure is a Swiss linguist who laid the foundations of semiology and structural linguistics, who stood at the origins of the Geneva Linguistic School.

Saussure was born on November 26, 1857 in Geneva (Switzerland) in a family of French emigrants. At the age of 18 he entered the Leipzig University in Germany. In 1879, Ferdinand de Saussure published a Memoir on the original vowel system in Indo-European languages. This memoir immediately placed Saussure among the leading authorities in linguistics of the time. In 1880 he received his doctorate.

Then, Ferdinand de Saussure moved to France, and in 1881-1891. taught Sanskrit at the School of Higher Studies in Paris. In the same years, Saussure served as secretary of the Parisian Linguistic Society. While working there, he had a significant impact on the development of linguistics.

From 1906 to 1911 Saussure lectured on comparative grammar and general linguistics at the University of Geneva.

After his death, in 1916. his most important work "Course of General Linguistics" was published. This book is a reconstruction of the course, compiled from student notes by Saussure's students Charles Bally and Albert Seschet. Thanks to the publication of this work, Ferdinand de Saussure's views on the nature of language and the tasks of linguistics became widely known.

Memoir on the original vowel system

Mumoir on the original vowel system in Indo-European languages was written in 1878 and published in 1879. It glorified the 21-year-old Saussure in scientific circles, although it was received ambiguously.

In the Memoir, which was already marked by a structuralist approach to the language, Saussure put forward a hypothesis about the existence in the Indo-European language of vowels that are lost in the Indo-European daughter languages, the conjugations of which can be discovered by studying the Indo-European root and vowel alternation.

The ideas outlined in "Mumuar" began to actively develop only 50 years later.

In 1927. already after the death of de Saussure, Kurilovich (Polish linguist) found confirmation of Saussure's theory in the deciphered Hittite language - a phoneme was discovered, which, according to Kurilovich's assumption, should have existed in the Indo-European proto-language. After that, the laryngal hypothesis, based on the ideas of de Saussure, began to gain more and more followers.

Today, Memoir is viewed as a model of scientific foresight.

General linguistics course

A Course in General Linguistics was published posthumously in 1916 by Charles Bally and Albert Seschet based on Saussure's university lectures. Bally and Seschet may, to some extent, be considered co-authors of this work, since Saussure had no intention of publishing such a book, and much of its composition and content, apparently, was brought in by the publishers (much is not in Saussure's detailed lecture notes known to us, although of course he could share ideas with colleagues in private conversations).

Semiology, which Ferdinand de Saussure creates, is defined by him as "the science that studies the life of signs within the framework of the life of society." "She must reveal to us what the signs are, what laws are they governed by." De Saussure argues that semiology should be a part of social psychology and determining its place is the task of the psychologist. The task of the linguist is to find out what distinguishes language as a special system in the totality of semiological phenomena. Since language is one of the sign systems, linguistics turns out to be a part of semiology. De Saussure sees the definition of the place of linguistics among other sciences precisely in its connection with semiology: "if for the first time we manage to find linguistics a place among the sciences, this is only because we connected it with semiology."

One of the main provisions of the "Course of General Linguistics" is the distinction in speech activity between language and speech: "Separating language and speech, we thereby separate: 1) the social from the individual

2) essential from collateral and more or less accidental

Language is a "function of the speaking subject", "a product passively registered by the individual," which "does not presuppose preliminary reflection," and "analysis in it appears only in the area of classifying activity."

Speech is an “individual act of will and understanding”, containing, first, “combinations by which the speaking subject uses the linguistic code,” and secondly, a psychophysical mechanism that allows the subject to objectify these combinations; "There is nothing collective in speech." Speech activity "has a heterogeneous character," and language "is a phenomenon inherently homogeneous: it is a system of signs in which the only essential is the combination of meaning and an acoustic image."

Speech activity, speech act, according to Saussure, has three components:

1.physical (propagation of sound waves)

2.physiological (from the ear to the acoustic image, or from the acoustic image to the movements of the speech organs)

3. psychic (firstly, acoustic images - a psychic reality that does not coincide with the sound itself, a mental idea of physical sounding; secondly, concepts).

Although language does not exist outside the speech activity of individuals ("this is not an organism, this is not a plant that exists independently of a person, it does not have its own life, its own birth and death"), nevertheless, the study of speech activity should begin precisely with the study of language as the foundations of all phenomena of speech activity. Linguistics of language is the core of linguistics, linguistics "in the proper sense of the word."

A linguistic sign consists of a signifier (acoustic image) and a signified (concept). A linguistic sign has two main properties:

1. An arbitrary connection between the signifier and the signified, that is, in the absence of an internal, natural connection between them.

2 The signifier has an extension in one dimension (in time).

Language is made up of linguistic entities - signs, that is, the unity of the signifier and the signified.

Linguistic units are linguistic entities delimited among themselves. Units are revealed thanks to concepts (a separately taken acoustic component cannot be divided): one concept corresponds to one unit.

A linguistic unit is a piece of sound (mental, not physical), meaning a certain concept.

Language is a system of meanings. Meaning is what the signifier is to the signifier. The significance of the sign arises from its relationship with other signs of the language.

Both the concepts and the acoustic images that make up the language are values - they are purely differential, that is, they are determined not positively by their content, but negatively by their relations to other members of the system. There are no positive elements in the language, positive members of the system, which would exist independently of it; there are only semantic and sound differences. "That which distinguishes one sign from others is all that makes it up." The language system has a number of differences in sounds associated with a number of differences in concepts. Only the facts of combinations of data signifiers with data signifiers are positive.

There are two kinds of meanings, based on two kinds of relationships and differences between elements of the language system. These are syntagmatic and associative relationships.

Syntagmatic relations are relations between linguistic units following each other in the stream of speech, that is, relations within a number of linguistic units existing in time. Such combinations of linguistic units are called syntagmas. Associative relationships exist outside the speech process, outside of time. These are relations of community, similarities between linguistic units in meaning and in sound, or only in meaning, or only in sound in one way or another.

The main provisions of the "Course of General Linguistics" also include the distinction between diachronic (historical and comparative) and synchronic (descriptive) linguistics. According to Saussure, linguistic research is only adequate to its subject when it takes into account both the diachronic and synchronic aspects of language.

Diachronic inquiry should be based on carefully executed synchronic descriptions; the study of changes taking place in the historical development of language, says Saussure, is impossible without a careful synchronous analysis of the language at certain moments of its evolution. Comparison of two different languages is possible only on the basis of a preliminary thorough synchronous analysis of each of them.

Bibliography:

"Philologist's Dictionary"

§ 1. LIFE AND CREATIVE WAY

One of the prominent linguists of the 20th century, the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) was born in Geneva into a family of scientists. From childhood, his ability to languages was manifested: he knew Greek and Latin. In 1875, de Saussure began studying at the University of Geneva, and in 1876 he moved to Leipzig, where such prominent linguists of the time as G. Curtius and A. Leskin taught comparative linguistics. He spent two years in Leipzig, interested mainly in comparative language studies. The result of his studies in this area was the study "On the original vowel system in Indo-European languages" (1879); in this work, the description of individual facts of the language, characteristic of young grammarians, is replaced by a jj £ -_ _ flat description of the system. The young grammarians greeted de Saussure's work coldly. N.V. Krushevsky highly appreciated the research of the young scientist, who tried to apply the data obtained by de Saussure to the analysis of the Old Slavonic language. (The creative aspirations of I. CHA.Baudouin de Courtenay, Krushevsky and de Saussure in this period largely coincided; it was not for nothing that de Saussure later said that these two Russian scientists came closest to a theoretical examination of language.) the dissertation of de Saussure "Genitive absolute in Sanskrit" (1880).

Since 1880 de Saussure has lived in Paris and takes an active part in the work of the Parisian Linguistic Society (since 1882 - Deputy Secretary of the Society). In 1884 he began lecturing at the Higher Practical School, and from that time on his scientific activity was limited to teaching. However, as a foreigner, de Saussure had no right to head a department in any of the higher educational institutions in France. In 1891 he returned to his homeland. At the University of Geneva, he first became an extraordinary professor of comparative historical grammar of Indo-European languages, then an ordinary professor of Sanskrit and Indo-European languages, and from 1907 he headed the department of general linguistics.

During his teaching career, de Saussure did not publish a single general theoretical work, although he continued to study the theory of language and the logical classification of languages. His deep reflections on the problems of the essence of language were reflected in the course of general linguistics. Read by de Saussure in 190G-1912.

three courses in general linguistics formed the basis of the "Course in General Linguistics" (1916), published posthumously; the book is a recording of his lectures by S. Bally and A. Sesche 1. The "Course in General Linguistics" gained worldwide fame, was translated into many languages and had a great influence on the formation of various directions of linguistics in the XX century.

§2. ORIGINS OF THE LINGUISTIC CONCEPT

The linguistic concept of F. de Saussure is based on the criticism of the views of young grammarians, the desire to more deeply comprehend the structure of language and the essence of its basic units, the use of data from other sciences to understand the nature of language. At the same time, de Saussure creatively perceived the achievements of contemporary linguistics.

In solving the main problems of linguistics, about the nature, essence and specifics of language, de Saussure was greatly influenced by ideas

| French sociologists-positivists O. Comte, E. Durkheim and

G. Tarda (see Chapter 12, §3).

* In the "Course of Positive Philosophy" (1830-1842) Comte first introduced the term "sociology". According to Comte, it is necessary to describe the studied phenomena without penetrating into their essence, only to establish the smallest number of external connections between them. These connections are determined on the basis of the similarity of phenomena and their sequential location in relation to each other. Sociology Comte divides into social statics, which should describe the state of society, and social dynamics, which investigates the impact of moral incentives on the transformation of the world.

The problem of the essence of social phenomena is examined in detail in the work of Durkheim "Method of Sociology" (1899); he writes that society is "a kind of psychic being, an association of many consciousnesses." Denying the existence of the objective world, Durkheim believed that objectively, outside of man, there is only the so-called "social fact", "collective consciousness", that is, beliefs, customs, way of thinking, actions, language, etc. Durkheim deduces " the law of compulsion ", according to which any social fact is compulsory: forcing a person to obey, he at the same time prescribes a certain behavior for a person.

These idealistic tenets of Durkheim's teachings influenced de Saussure's linguistic views. As Durkheim believes that society is a mechanical association of many consciousnesses, so de Saussure believes that ^ shk ^ is “a grammatical system that potentially exists in every brain, or, better to say, in the brains of a whole set of individuals, for language does not exist completely in none of them, it exists in full measure only in the mass "2. Deist-

1 In 1957 the Swiss scientist R. Godel published the book “Handwritten

sources of the "Course of General Linguistics" by F. de Saussure ", in which he questions

the authenticity of individual provisions of de Saussure in the form in which they were

unveiled by Balli and Seshe. A consolidated publication is currently underway

the text of the book in comparison with all handwritten materials.

2 Cit. according to the book: S o s yur F. de. Course of general linguistics. M., 1933.

Outside of Durkheim's law of compulsion is also noted by de Saussure when analyzing the motivation of a linguistic sign. Emphasizing the conditionality of “language,” he believes that “if in relation to the idea he depicts the signifier appears to be freely chosen, then, on the contrary, in relation to the linguistic community that uses it, it is not free, it is imposed.<...>It is as if they say to the language: "Choose!" De Saussure views language as a social fact that exists outside of a person and is "imposed" on him as a member (of a given collective.

I The influence of Durkheim also affected de Saussure's doctrine of

object and point of view in science and language. Durkheim claimed that we

HoTGy ^ 1rr1] p ^ added to the "" "^ the world only on the basis of subjective

perceptions. De Saussure, developing this idea in relation to

linguistics, writes: “The object does not at all predetermine the point of view;

on the contrary, it can be said that the point of view creates the object itself. "

In his opinion, only a "superficial observer" can admit

the reality of the existence of language. Words exist only to the extent

in which they are perceived by the speaker. Npugpmu w ssch f act of being

language development with creates an object and ^ traces ^ nid ^] 1 our point of view on

language. "~ ~ ---

Another philosopher and sociologist, Tarde, in his work "Social pre-jrHjja" (1895) declared the basis of social life the law of imitation. The relationship between society and the individual is the main problem of Tarde's composition, for the solution of which he also draws on the facts of language as a social phenomenon. According to Tardu, there is nothing in society that is not in the individual. But a minority of people are assigned the role of inventors, and the lot of the majority is imitation. This position of Tarde was reflected in de Saussure's solution of the problem of language and speech: “By separating language and speech, we thereby separate: 1) the social from the individual; 2) essential from collateral and more or less accidental. " However, de Saussure did not show the dialectic of the relationship between language and speech.

De Saussure was also familiar with the works on political economy *. Referring to these works [mainly by A. Smith and D. Ricardo, who talk about two types of value (value) - consumer value and exchange value], he argues that in order to establish the significance (value) of a linguistic sign, it is necessary: that dissimilar thing that can be exchanged for something whose value is to be determined, and 2) the presence of some similar things that can be compared with the value of which we are talking about. " The formation of de Saussure's theoretical views was also influenced by his criticism of the provisions of comparative historical linguistics. Former linguistics, according to de Saussure, devoted too much space to history and therefore was one-sided: it studied not the system of language, but individual linguistic facts (“comparison is not

1 See: N. A. The main thing in the linguistic concept of F. de Saussure.- "Foreign languages at school." 1968, no. 4.

more as a means of recreating the past<...>; states enter this study only in a fragmentary and very imperfect manner. This is the science founded by Bopp; that's why the understanding of his language is half-hearted and shaky. " Although the comparative historical linguistics of the 80s of the XIX century. and achieved significant success, but not all scientists completely agreed with the teachings of the young grammarians. The American linguist W. Whitney, the Russian "linguists I. A. Baudouin de Courtenay and N. V. Krushevsky and others tried to pose and solve major theoretical problems. - *

In Whitney's book The Life and Development of Language (1875), de Saussure could get acquainted with such problems of general linguistics as the relationship between language and thinking, the relationship between individual and social phenomena, etc. Whitney defines language as a set of signs used for expression of thoughts. He notes two features of the signs of the human language: their arbitrariness and convention. / The arbitrariness of the sign lies in the absence of a connection between the word / and the idea expressed by it, and the conventionality - in its use by the society to which the speaker belongs. Considering language as a complex of correlative and mutually supportive parts, Whitney approached the recognition of the systemic nature of language. He also tried to understand the structure of linguistic units, the relationship of their components. Comparison of the linguistic views of Whitney and de Saussure shows the undoubted influence of the American linguist, but de Saussure does not repeat, but reinterprets the provisions of Whitney 1.

De Saussure also highly appreciated the works of the Russian linguists Baudouin de Courtenay and Krushevsky. Some of their positions are also reflected in the works of de Saussure; "A lot, expressed by Saussure in his deeply thought-out and elegant presentation, which became common property and caused universal delight in 1916, - wrote L. V. Shcherba, - we have long known from the writings of Baudouin" 2.

How did the theoretical views of de Saussure, Baudouin de Courtenay and Krushevsky coincide and how did they differ? Baudouin de Courtenay put forward his understanding of the system of language as an aggregate, the parts of which are interconnected by relations of meaning, form, sound, etc. He said that the sounds of different languages have different meanings, in accordance with the relationship to other sounds. In a system of language based on relationships, Baudouin de Courtenay distinguishes levels - phonetic, morphological, semantic. He constantly points to the historical variability of the concept of a system. De Saussure also understands language (“dzyk 'is a system, all the elements of which form a whole”). True, he bases his understanding of the system on opposition as a "particular case of relations."

De Saussure's "Course in General Linguistics" examines in detail such an opposition as language - speech associated with the relation

1 See: N. A. Slyusareva. Some half-forgotten pages from history

linguistics (F. de Saussure and W. Whitney) .- In the book: General and Romance Linguistics

M., 1972.

2 Shcherb and L.V. works on linguistics and phonetics, t 1 L., 1958

from 14.

Neither social and individual (psychological) in language. Russian linguists have distinguished between language and speech for a long time. Back in 1870, Baudouin de Courtenay drew attention to the difference between human speech in general from individual languages and dialects and, finally, from the individual language of an individual person. De Saussure considers language to be a social element of speech activity, and speech is an individual act of will and understanding, that is, he opposes the language of speech. And in the interpretation of Baudouin de Courtenay, language and speech constitute an interpenetrating unity, they condition each other's reality: an individual language exists only as a kind of language. De Saussure treats the social as psychological, opposing it to the individual. The collective-individual existence of language, according to Baudouin de Courtenay, presupposes inseparability in the language of the individual and the general, since the individual is at the same time universal.

Baudouin de Courtenay establishes the laws of the development of language in time and the laws that determine the functioning of language in its simultaneous state, that is, the laws of the historical development of language, its dynamics (what de Saussure later called the diachrony of language), and the laws of the modern state of language (synchronic , according to de Saussure, the state of the language). De Saussure contrasted the synchronic point of view with the diachronic one, considered the synchronic aspect more important.

The formation and development of de Saussure's creative views was also influenced by the theory of the types of relations in the language of Krushevsky. The position of words in the language system, Krushevsky believed, is determined either by adjacency association, when the connection between words is carried out or in their linear sequence (for example, deposit money, big house), or in the identity of the meanings expressed by them, or by association by similarity, when words are connected on the basis of external similarity or similarity in meaning (for example, harrow, furrow- external similarity; drive, carry, carry- community of meaning; near, spring, external- commonality of the suffix). De Saussure also distinguishes two types of relationships - syntagmatic and associative. By syntagmatic relations, he understood relations based on a linear character, based on length (re-read, human life); these are associations by contiguity in Krushevsky. By associative relations, de Saussure understood the relationship of words that have something in common with each other, similar or by root (teach, teach, teach), either by suffix (training, instruction), or by general meaning (training, education, teaching etc.); Krushevsky called such relationships associations by similarity. De Saussure recognized only these types of relationships, and Krushevsky noted that the two types of relationships do not exhaust all the means that our mind has in order to combine the entire mass of dissimilar words into one single whole.

De Saussure proceeded exclusively from the opposition of specific units of language. Krushevsky, on the other hand, drew attention to what unites them, which allows you to combine words in the mind into systems or nests.

There is no doubt that Saussure's definition of a sign as the unity of the signified and the signifier is similar to the definition of a sign given by Krushevsky: a word is a sign of a thing, and ideas about a thing (signified) and about a word (signifying) are linked by the law of association into a stable pair.

So, all the problems posed by de Saussure in the "Course of General Linguistics" (the systemic understanding of language, its sign character, the relationship between the current state of language and its history, external and internal linguistics, language and speech) have already been posed in the works of his predecessors and contemporaries: W. Humboldt, Whitney, Baudouin de Courtenay, Krushevsky, M. Breal and others. Honored surely, by combining these problems, he created a general theory of language, though not free from contradictions and not giving a final solution to all questions.

§3. DEFINITION OF LANGUAGE. THEORY OF LANGUAGE AND SPEECH

The problem of the relationship between language and speech was first posed

V. Humboldt, then A. A ^ Potebnya tried to solve it, and I. A, ... Ea ^,

__duen_de_ Courtenay. F. de_Saussure_ also develops various aspects of

you have this problem. ,

Separating language (langue) and speech (parole), de Saussure proceeds from his

understanding of speech activity (langage) as a whole, i.e. speech (re

act) and language stand out “within the general phenomenon, which is

speech activity takes place. " Speech activity from

rushes to both the individual and social spheres, invades that

some areas, such as physics, physiology, psychology, have an external

(sound) "and internal (mental) side. In the concept of de

Saussure, she acts as a concept of human speech in general, as

property inherent in man. The language is only a certain part,

true, the most important, speech activity (“language for us is speech,

activity minus speech itself ”). Language opposes *

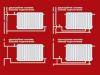

speech - this second side of speech activity. De Saussure presents the relationship between language, speech and speech activity in the form of a diagram:

Synchronicity

^ language<

speech activity <

^ diachrony

(langage) 1p high

Speech activity unites language and speech, the main difference between which is that language is social, and speech is individual. De Saussure constantly emphasizes that language is “a social element of speech activity in general, in this relationship to an individual who, by himself, cannot“ create ”a language or“ change it. ”In language, everything is social, everything is conditioned. as a social ~ * product is assimilated by each individual in a finished form

("Language is a treasure, which is deposited by the practice of speech in all who belong to one social collective").

However, while recognizing the social nature of language, de Saussure also emphasizes its mental nature; language is "associations held together by collective agreement, the totality of which constitutes language, the essence of reality located in the brain." This statement psychic The natural character of language, the mental essence of linguistic knowledge * gave some scholars reason to talk about the psychological sociologism of de Saussure's linguistic concept.

Speech in de Saussure's theory is “an individual act of will and understanding, in which it is necessary to distinguish: 1) combinations with the help of which the speaking subject uses the linguistic code in order to express his personal thought; 2) a psychophysical mechanism that allows him to objectify these combinations ”. On the other hand, £ ich __- “the sum of everything that people say, and includes: a) individual combinations, depending on the will of the speakers, b) acts of speaking, equally produced, necessary to perform these combinations. Consequently, there is nothing collective in speech: its manifestations are individual and instantaneous. "

Language and speech “are closely related and mutually presuppose each other: language is necessary for speech to be understandable and to produce all its effect; speech, in turn, is necessary in order for the language to be established; the historical fact of speech always precedes language. " Recognizing the inner unity of language and speech, de Saussure. ^ at the same time asserts that "these are two things completely different." 4) Such an unexpected conclusion is due to the properties that he distinguishes, defining language and speech:

1. Language is a social product, but speech is always individual. Each act of speech is generated by a separate individual, and the language is perceived in the form in which it was bequeathed to us by previous generations. Therefore, “language is not a function of the speaking subject, it is a product passively registered by an individual<...>... On the contrary, speech is an individual act of will and understanding. "

2. Language potentially exists in every brain as a grammatical system; the realization of these potentialities is speech. (As de Saussure said, speech refers to language as the performance of a symphony to the symphony itself, the reality of which does not depend on the way of performance.)

3. Language differs from speech as essential from incidental and incidental. Essential in the language are the normative facts of the language fixed by "linguistic practice, and all kinds of fluctuations and individual responses belong to side and accidental phenomena.

Deviations in speech.

One object can have such different properties, they must be distinguished: “A language, isolated from speech, is a subject accessible to separate study.<...>Not only the science of language can do without other elements of speech activity, but it is generally possible only if these other elements to it

not mixed. " Therefore, de Saussure requires a separate study of each of the aspects of speech activity, proposing to distinguish between two sciences - linguistics of language, which is the object of study of language, and linguistics of speech, which is of secondary importance and studies the characteristics of individual speech. The researcher, said de Saussure, “must choose one of two paths that are not possible to follow at the same time; you have to follow each of them separately ”; he himself was mainly engaged in the linguistics of the language.

- "" "After the publication of the" Course of General Linguistics ", there were many interpretations of Saussure's system" language - speech. " to language, and which to speech; the reason for these disputes is in the contradictory statements of de Saussure himself about the distinction between language and speech.

The merit of de Saussure is the definition of internal contradictions in speech processes. But having discovered these contradictions, he did not notice the organic connection between them. His opposition to language as a social product of speech as an "indivi-" dual fact is incorrect. Language is a means of common-n and I between people, this determines its social character. The development of the language is due to the development of that society, the needs of which

i rogo he serves. The reproduction of a language by many people cannot be homogeneous: various kinds of individual deviations arise, which, to a greater extent touching vocabulary than grammar and phonetics, do not change the social character of the language. But individual speech cannot exist apart from language. If there was nothing social in speech, it could not serve as a means of language acquisition.

Language as something in common is holistic in its structure. But the forms of manifestation of this common are manifold. Modern mass media (radio, television, cinema, etc.) are various forms of language manifestation. The same form of its implementation is speech - oral and written, dialogical and monologic, etc. Speech is not only individual, “it includes what is caused by a given communicative situation and can come to naught in another communicative situation. Language and speech not only differ, they are inconceivable without each other ”1.

§4. LANGUAGE AS A SYSTEM

The main merit of F. de Saussure to linguistics is that at the beginning of the XX century. he drew attention to the need to study language as a system, to analyze what in a language, being internal, determines its essence as a means of communication.

1 Budagov R.A. Language, history and modernity. M., 1971, p. 61-62.

The success of de Saussure's "Course in General Linguistics" was greatly facilitated by both the strict consistency of the presentation and the bright, unexpected comparisons. Thus, considering language as a system, de Sos-sur compares it with chess: “... Language is a system that obeys its own order. Comparison with the game of chess will help to clarify this, in relation to which it is relatively easy to distinguish what is external and what is internal: the fact that this game came to Europe from Persia is of an external order; on the contrary, everything that concerns the system and the rules of the game is internal. If I replace wooden figures with ivory figures, such a replacement is irrelevant to the system; but if I decrease or increase the number of pieces, such a change will deeply affect the "grammar of the game."

However, this comparison contains a number of inaccuracies. First of all, chess does not know national differences - the rules of the game are the same everywhere. A language, however, always possesses nat_donl-irbTW "TF categories that distinguish it from other national languages. Further, if the history of their origin is insignificant for us when playing chess, then the structure of the language is always greatly influenced by the conditions, in which the language was formed. As if feeling the insufficiency of the above definition, de Sos-sur introduces into the concept of a system an element of opposing linguistic units: just as playing chess is reduced to combining the positions of various figures, so language is a system, based on the opposition of its specific units.

/ Determination of the properties of one or another linguistic element ^ by comparing it with other linguistic elements - this is something new that distinguishes Saussure's understanding of the systemic nature of language. However, the concentration of attention only on oppositions led to the limitation of the content side of the language: "in the language there is nothing but differences", "in the language there are only differences without positive aspects." The question arises - what is hidden behind these differences? After all, they must distinguish between some real objects. Unfortunately, de Saussure does not give an answer to this question, he is silent about which specific units are hidden behind these relations, and calls for limiting the tasks of linguistics to the study of the category of relations.

De Saussure distinguishes between two types of relationships - syntagmatic and associative. "The syntagmatic relation is always there (in praesentia): it rests on two or more elements equally present in the actual sequence." In syntagmatic relationships, linguistic units line up, and by virtue of the principle of linearity, each unit is combined with neighboring units. Such combinations based on length, he calls si n ta g m aHmiG "Syntagma" can consist of two or more units (re-lire- "re-read", center tons- "against all", la vie humaine- "human life", s "il fait beau tempe, nous sortirons- "if the weather is good, we will go for a walk").

To what do syntagmatic relations relate - to language or to speech? On the one hand, de Saussure says: "All types of syntagmas constructed according to the correct forms must be attributed to language, and not to speech." But on the other hand, "in the field of syntagma, there is no sharp line between the fact of language, captured by a collective custom, and the fact of speech, which depends on individual freedom."

The second type of relationship de Saussure calls associative: "... An associative relationship connects absent elements (in absentia) into a potential, mnemonic series", they are "in the brain; they constitute the stock that each individual has a language for. " Having arisen in the human brain, associative relations unite words according to the common root (French. enseignement, enseigner, ensei-gnons; Russian teach, teach, teach) or suffix (fr. enseignement, armement, changement; Russian training, guidance, direction), based on the random similarity of the acoustic image (fr. enseignement and justement, where in the first word -ment-suffix of a noun, and in the second - adverbs; Wed Russian mash and right) or on the basis of common meaning (fr. enseignement, instruction, apprenlissage, education; Russian teaching, mentoring, enlightenment, teaching, coaching). It can be seen from the examples given that de Saussure includes not only morphological, but also semantic connections between words in associative relations, although he admits that the most characteristic of them are word connections within the inflectional paradigm.

De Saussure attached great importance to the theory of relations ("this whole set of established (usual) relations constitutes language and determines its functioning"). Each member of the system is determined by its connection with its other members both in space (syntagmatic relations) and in consciousness (associative, relations).

The position of the system of language as a set of interdependent elements received from de Saussure a concrete implementation in the doctrine of two types of relations. The interaction of these relationships is revealed in the process of speech, when composing phrases of all types, for example, What do you know ?, in which we select the desired option to you out of a number you, us etc.

De Saussure viewed the language system as a mathematically exact system. He believed that all relations in a language can be expressed in mathematical formulas, and used the mathematical term "member" to denote the components of a system. De Saussure noted two features of the system: a) all members of the system are in equilibrium, b) the system is closed.

The totality of relations determines the functioning of the language as a means of communication. This determines the social character of the language. But apart from language, there are other social phenomena - political, legal, etc. What distinguishes language from other social phenomena? Sign character, de Saussure answers, "language is a system of signs expressing ideas." Of paramount importance for understanding the linguistic concept of de Saussure is his doctrine of the linguistic sign.

§ 5. THE TEACHING ABOUT A LINGUISTIC SIGN

F. de Saussure defines language from the point of view of its symbolism: "Language is a system of signs, in which the only essential is the combination of meaning and acoustic image, and both of these elements are psychic in an" equal "measure." Further, he explains his understanding of the sign: "we call a sign a combination of a concept and an acoustic image." An acoustic image is not a material sound, but an imprint of sound, a representation received by a person through the senses. Since an acoustic image is a psychic imprint of sound and a concept has a psychic property, de Saussure comes to the statement that “ language the sign is thus a two-sided psychic essence. "

Since in common usage a sign denotes only an acoustic image, de Saussure, emphasizing the linguistic essence of his definition of a sign, introduces special terms: with KchI i image ", respectively, with the terms" Ve na cha emo e "and" signifying ".

Linguistic signs are not abstractions, but realities that are in the human brain. They represent those concrete entities ", which the linguistics of language deals with. As an example of a linguistic sign, de Saussure cites the word as something central in the mechanism of language. But since signs can be not only words, but also words are frequent, then look for a specific unit of language. "

Having defined a linguistic sign as a mental entity, de Saussure concludes that linguistics of language, the science that studies language as a system of signs of a special kind, is part of semiology - the science of signs in general. And since semiology is a part of general psychology, then linguistics (linguistics of language) should be considered as a part of psychology.

Having compiled a general idea of a linguistic sign, de Saussure establishes its features that distinguish it from units of other sign systems. The first principle of a linguistic sign is formulated by him briefly: the linguistic sign is arbitrary; the connection connecting the signifier with the signified is arbitraryLToch "by the arbitrariness of the sign, de Saussure understands the absence of any relationship with the object indicated by this sign. Thus, the concept of" sister "is not connected by any internal relations with the sequence of sounds of the French word soeur and could be expressed by any other combination of sounds.

The importance of this principle is enormous, for it "subordinates to itself the entire linguistics of the language." However, the arbitrariness of a linguistic sign is limited by the laws of the development of a given language. The sign is absolutely arbitrary in some part of the words; in most words in the general system of language, the arbitrariness of the sign does not exclude motivation. If we take the floor Fourty, then it is not motivated by anything, its internal form is unclear. But the word fifty, related to its constituent parts (five and ten), already can

tivated. Inner form in a word fifty as transparent as, for example, in a word icebreaker, and the origin of words five and ten without etymological analysis it is no longer clear.

The existence of motivated words makes it easier for a person to master the language system, since the complete arbitrariness of signs would make it difficult to memorize them. “There are no languages,” writes de Saussure, “where there is nothing motivated; but it is inconceivable to imagine a language where everything would be motivated. " ^ Languages with the maximum lack of motivation, he calls the lexico-logi h e ^ s _ k and "mi, as minimal - grammatical. These are" like two poles between which the entire system develops, two opposite currents along which the movement of the language is directed: from one hand, the propensity to use a lexicological tool - ■■ unmotivated sign, on the other hand - the preference given to the grammatical instrument - the construction rule ”. Thus, according to de Saussure, there is much more unmotivated in English than in German; an example of an ultra-lexicological language is Chinese, and an ultra-grammatical language is Sanskrit. The consequence of "action, the principle of arbitrariness of the linguistic sign, de Saussure considers the antinomy" variability - immutability "of the sign. he does not know \ any other law, except for the law of tradition, and only because it can be arbitrary, that is based on tradition ").

But at the same time, linguistic signs are subject to change. The principle of variability of a sign is associated with the principle of continuity ^) In the process of the historical development of a language, the variability of a sign manifests itself in a change in the relationship between the signifier and the signified, that is, either the meaning of the word, or the sound composition, or both sound and meaning [so, lat. pesag- "to kill" has become in French poyeg -"Drown (in water)"]. "Language by its very nature is powerless to defend itself against factors that constantly shift the relationship between the signified and the signifier," - this is one of the consequences of the arbitrariness of the sign, asserts de Saussure. V de Saussure also puts forward the second principle - the principle of line n o - "* s t and sign." b) this extension lies in one dimension: it is a line. ”In other words, acoustic images cannot appear simultaneously, they follow each other, sequentially, forming a linear chain.

But only the sounds of words can be arranged sequentially, and each sound has peculiar sound characteristics (deafness - voicedness, softness - hardness, explosiveness, etc.). Moreover, these signs appear in the sound not linearly, but in volume, that is, the sound simultaneously possesses several signs. Consequently, from the point of view of modern phonology, Saussure's principle of lin "her-

Nosti is about sounds in a word, not phonemes. De Saussure himself says that the principle of linguistic character characterizes speech, not language, therefore, cannot be the principle of a linguistic sign as a member of the system.

If arbitrariness is the main thing for a linguistic sign, then why is there no general sudden change in a language consisting of such signs? De Saussure points to four obstacles to this:

1) the arbitrariness of the sign "protects the language from any attempt aimed at changing it": it is impossible to decide which of the arbitrary signs is more rational;

2) the plurality of signs used by the language makes it difficult to change them;

3) the extreme complexity of the language system;

4) “at every given moment, the language is the business of each and every<...>... In this respect, it can in no way be compared with other social institutions. Prescriptions of the law, rituals of religion, sea signals, etc., attract only a limited number of persons at a time and for a limited period; on the contrary, everyone takes part in language every minute, which is why language is constantly influenced by everyone. This one basic fact is enough to show the impossibility of a revolution in him. Of all social institutions, language represents the smallest field for initiative. It cannot be torn away from the life of the public mass, which, being inert by nature, acts primarily as a conservative factor. "

One of the main points in de Saussure's linguistic theory

is his teaching about the value of a linguistic sign, or about

its significance. “As part of the system, the word is not clothed

only by meaning, but also - mainly - by significance, and this

already quite different. Few are enough to confirm this.

examples. French word tnouton may be the same as

Russian word ram, but it does not have the same significance as it,

and this is for many reasons, among other things, because, speaking about at

a piece of meat cooked and served on the table, the Russian will say mutton

on, but not ram. The difference in significance between ram and mouton associated with

the fact that the Russian word has another term along with it, corresponding

which is not found in French ”. In other words,

the meaning of a word in the lexical system of one language may not correspond

to follow the meaning of the same word in another language: in Russian

you can't say "roast ram", but surely - roast from

lamb, but in french gigot de mouton(literally "roast from

ram "). "

Meaning and significance are also not the same: significance is included in meaning as a complement. It is in the division of the semantics of the word into two parts - meaning and significance - that de Saussure penetrates into the internal system of language: it is not enough to state the fact that a word has one or another meaning; it must also be compared with meanings similar to it, with words that can be opposed to it. Its content is determined only through

D attraction of the existing outside of it. The significance of a sign is determined by i only by its relation to other members of the language system. "The concept of value refers not only to words, but also to any phenomena of the language, in particular to grammatical categories. So, the concept of number is in any language. The plural of French and Old Church Slavonic or Sanskrit is the same in meaning (denotes many objects) If in French the plural is opposed to the singular, then in Sanskrit or Old Church Slavonic, where, in addition to the plural, there was also a dual to denote paired objects (eyes, ears, arms, legs), the plural is opposed to both the singular and the dual. It would be inaccurate to attribute the same importance to the plural in Sanskrit and French, Old Church Slavonic and Russian, since in Sanskrit or Old Church Slavonic it is impossible to use the plural in all those cases where it is used in French or Russian. "... Consequently, - concludes de Saussure, - the significance of the plural depends on what is outside and around him."

A similar example can be given with the grammatical category of tense. The meaning of time is available in all languages, however, the significance of the three-term category of time in Russian (present, future, past) does not coincide with the significance of the polynomial category of time in German, English, French. Based on these examples, de Saussure comes to the conclusion that significance is an element of the language system, its function. ""

De Saussure distinguishes between conceptual and material aspects of value (significance). The conceptual aspect of value is the ratio of the signified to each other (see examples with words ram and mouton). The material aspect of value is the relationship between the signifiers. "It is not the sound itself that is important in the word, but those sound differences that make it possible to distinguish this word from all others, since they are the carriers of meaning." This statement de Saussure illustrates with the example of the Russian genitive plural hands, in which there is no positive sign, that is, a material element that characterizes a given form, and its essence is comprehended through comparison with other forms of this word (hands- hand).

The doctrine of the significance of the linguistic sign developed by de Saussure is of great importance for the study of the lexical, grammatical and phonetic systems of the language. But at the same time, from the point of view of the Marxist-Leninist theory of knowledge, it also contains a number of weak provisions. De Saussure believes that we observe “instead of pre-given ideas of significance, arising from the system itself. Saying that they correspond to concepts, it should be understood that these latter are purely differential, that is, they are not positively defined by their content, but negatively by their relations with other elements of the system. " Hence it follows that the significance of a sign as part of the content side of the language (signified) is determined by the relation

The subject not to reality, but to other units of the language, the place occupied in the system of units of the language (the meaning of the word ram is determined by the place of this word in the language system, and not by the fact that it denotes a four-legged cloven-hoofed animal). If for de Sos-sur. Concepts (meanings) are formed by the system, then for the Soviet language-guides they are the result of the reflective ((cognitive) activity of children. 1 .

De Saussure excludes the material substratum from the concept of value (significance): “After all, it is clear that sound, a material element, cannot by itself belong to language. It is something secondary for the language, only the material it uses. All conventional values (significance) in general are characterized by precisely this property not to mix with a tangible element that serves them as a substrate. " The linguistic category of value, extremely exaggerated by it, replaces everything.

Thus, a deeply and subtly noted feature of the language system, being elevated to the absolute, led to the understanding of the language system as a set of pure relations, behind which there is nothing real. It was this idea of de Saussure that was developed by L. Elmslev, the founder of glossmatics, the Copenhagen school of structuralism (see Chapter 13, § 7).

To prove the position of language as a system of pure meanings (values), de Saussure turns to the problem of the relationship between thinking and language, or idea and sound. He believes that our thinking is a formless and vague mass, where there are no real units, and looks like a nebula. The sound chain is also an equally formless mass, plastic matter, which is divided into individual particles. The division of both masses occurs in the language, for it serves as "an intermediary between thought and sound, and mustard in such a way that TTx unification inevitably leads to a mutual delimitation of units." It is impossible to separate language and thinking, for “language can be ... compared to a sheet of paper; thought is its front side, and sound is its back; you cannot cut the front side without cutting the back; so in language it is impossible to separate neither thought from sound, nor sound from thought; this can only be achieved through abstraction. " The linguist works in a borderline area where elements of both orders are combined. De Saussure's comparison is interesting, but it does not provide anything for understanding the essence of the question of the relationship between language and thinking.

§ 6. THE TEACHING ABOUT SYNCHRONY AND DIACHRONY

F. de Saussure figuratively called the opposition of language and speech the first crossroads encountered on the path of a linguist. He called the vtya intersection the opposition with and nx p about hV and and

1 See: V.M. Solntsev, The Signity of Language and the Marxist-Leninist Theory of Knowledge.- In the book: Leninism and Theoretical Problems of Linguistics. M., 1970.

diachrony and, that is, consideration of the language both at a given moment of its state, and in terms of its historical development. According to de Saussure, “everything that relates to the static aspect of our nauTsh, ~ dyach] is synchronous everything that concerns evolution. The nouns c and n x p 0) N and diachrony will respectively denote the state of the language and the phase of evolution. "

When learning a language, de Saussure considers it absolutely necessary

to distinguish its synchronic consideration from the diachronic one and in

in accordance with this, distinguishes between two linguistics - synchronic

and diachronic, specifying the tasks of each of them: “C and n-

chronic linguistics will deal with logical ^ and

psychological relationships linking coexisting

elements and forming a system, studying them as. they take

toil with the same collective consciousness. Diachroniche

Sky linguistics, on the other hand, will study relationships,

connecting elements in order of sequence, do not perceive

shared by the same collective consciousness, - „

elements that are replaced by one another, but not framed

systems ". O

Elements of a language that exist simultaneously or

following each other in time, de Saussure

considered it possible to place on the axes simultaneously

ness (AB) and sequence (CD). Illustrating D

these provisions, he spoke about the transverse and longitudinal

n cut of a tree: the first gives a picture of coexistence,

i.e. synchronicity, and the second is a picture of the follower

development of fibers, i.e. diachrony.

If synchronic linguistics studies language as a system, then

^ the object of diachronic linguistics does not form a system); otherwise

^ [Gvorya, synchronic linguistics deals with language, and diahryu -__

Schnicheskaya - with speech. Every language change is individual

“Shchi is a fact of speech; repeated often, it is accepted collective->.

bom and becomes a fact of the language. Thus, the delimitation of syn- D

chronic and diachronic linguistics is associated with de Saussure with

distinguishing between language and speech. -, ..-..-

Two reasons compel de Saussure to study a language by the method of two linguistics: a) the multiplicity of signs "absolutely prevents the simultaneous study of relations in time and relations in the system" and b) "for sciences operating with the concept of value, such a distinction becomes a practical necessity." IV What is the relationship between synchronic and diachronic linguistics? De Saussure believes that “language is a system, all parts of which can and should be considered in their synchronic connection. Changes that occur in the entire system as a whole, up to only in the "relations" of one or the other of its elements, can be studied only outside., Its "."<...>"This is essentially a difference between alternating elements and coexisting elements."<...>prevents the study of those and others in the system of one science ”. He gives preference to synchronic language learning, for “the synchronic aspect is more important than the dia-

7? a room 169; 193

chronic, since for the speaking masses only he is the true and only reality ”.

From the juxtaposition of synchronicity and diachrony, de Saussure made

serious conclusions:

1. He believes that some forces are found in synchronicity, and others in diachrony. These forces cannot be called laws, since any law must be general and binding. The forces, or rules, of the synchronous state of a language are often general, but never "become obligatory. The forces of the diachronic state are often presented as obligatory, but never appear to be general.

2. De Saussure argues that the synchronous plane of one language is much closer to the synchronous plane of another language than to its past (diachronic) state. Thus, it turns out that the synchronous state of the modern Russian language is closer to the synchronous state of, say, the Japanese language than to the diachronic state of the Old Church Slavonic. The inconsistency of this point of view is obvious.

To separate diachrony from synchronicity, the history of a language from its current state, is also inappropriate because the language system is a product of a long historical development and many facts of a modern language become understandable only when its history is known. In order to understand the difference between combinations in modern Russian two houses and five houses, you need to know what the form of the dual was at home, determining this difference.

If in the study "On the original vowel system in Indo-European languages" de Saussure applies the principle of consistency to the first history of Indo-European languages, now he deprives the history of the language of consistency. De Saussure believes that the system of language manifests itself only in synchronicity, because in itself it is unchangeable. How do language changes take place? Tearing diachrony away from synchronicity, de Saussure explains all linguistic changes as pure chance. However, sensing the precariousness of such an explanation, he adds that traditional comparative historical grammar must give way to descriptive synchronous grammar, and a grammar that studies the current state of the language must be updated with a historical method that will help to better understand the state of the language. Emphasizing the importance of studying the synchronous state of language, de Saussure seriously shook the theoretical foundations of traditional comparative-historical linguistics and paved the way for the emergence of new methods of language analysis.

§7. EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL LINGUISTICS |

The last opposition, pointed out by F. de Sl'Sur, and which is also important for understanding the essence of language, is the opposition of external and internal linguistic sticks, that is, external and internal elements of the language.

Of the non-linguistic factors influencing the language, de Saussure notes, first of all, the connection between the history of the language and the history of the nation. These stories intertwine and influence each other, he said; on the one hand, the customs of a nation are reflected in its language, and on the other, to a large extent, it is the language that forms the nation. Conquests, colonization, migration, language policy affect the boundaries of the spread of the language, the ratio of dialects within the language, the formation of a literary language, etc. Great historical events (for example, the Roman conquest) had enormous consequences for linguistics. To external linguistics, de Saussure also includes everything that has to do with the geographical spread of languages and their dialectal fragmentation.

Non-linguistic, extralinguistic factors are explained

some linguistic phenomena, for example „borrowing. But external

factors do not., affect (the system of language itself] £ a. De Saussure emphasizes

~ means \ "that they are not determinative, since they do not concern

of the very mechanism of language, Xiu ~ b1] uGrennegb ~ structure.

De Saussure sharply distinguishes external from internal linguistics. V. Humboldt, I. A. Baudouin de Courtenay, H. Gabelentsi and other linguists touched upon the problems of the essence of the external and the internal in the language, the role of external factors. The merit of de Saussure is that, opposing the study of the language only in connection with the history of the people, he drew the attention of linguists to the inner - lin gviskhi ke “-

But de Saussure's distinction between external and internal linguistics seems clearly untenable. To consider a language social in nature and at the same time to deny the influence of society on the language is to admit an obvious contradiction.

From all of the above, the conclusion logically follows, which concludes the book of de Saussure: "The only and true object of linguistics is language, considered in itself and for itself." De Saussure is right in asserting the need for an independent existence of linguistics (linguistics until the beginning of the 20th century was part of either philosophy or psychology). But a linguist, while studying a language, cannot and should not consider the language "in itself and for itself." Language cannot be taken away from the society whose needs it serves; we must not forget the most important function of language - to serve as a means of communication. The requirement to learn the language "for oneself" inevitably presupposes the impoverishment of the content side of linguistics. "

§8, THE IMPORTANCE OF THE LINGUISTIC CONCEPT OF F. DE SOSSUR FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF LINGUISTICS OF THE XX CENTURY.

In 1963, when the fiftieth anniversary of the death of F. de Saussure was celebrated, the famous French linguist E. Benveniste wrote that in our time there is hardly a linguist who would not owe something to de Saussure, as there is hardly such a common a theory of language that did not mention his name. Despite some exaggeration

Reading this assessment, it should be said that the provisions of de Saussure's theory had a great influence on the subsequent development of linguistics.

Many of de Saussure's theoretical propositions were expressed in the works of representatives of the Kazan linguistic school - I. A. Baudouin de Courtenay, N. V. Krushevsky, V. A. Bogoroditsky. These scholars with the independence and originality of linguistic thinking destroyed the usual canons of classical linguistics. The Soviet linguist E. D. Polivanov, who studied under Baudouin de Courtenay, wrote that "in the development of general linguistic problems, Russian and Polish scientists of the previous generation were not only on a par, but also far ahead of their contemporary and contemporary Western Europeans." And he reacted rather harshly about the work of de Saussure: although the book was perceived by many as a kind of revelation, it “contains literally nothing new in the formulation and resolution of general linguistic problems in comparison with what Baudouin had obtained from us a long time ago and Baudouin school "1. Academician L. V. Shcherba writes about the same: “When in 1923 we received in Leningrad“ Cours de linguistique generale ”de Saussure” a (posthumous edition of lectures on general linguistics by the famous linguist, professor at the University of Geneva, - an excellent book and made a great impression in the West), they were struck by the numerous coincidences of Saussure's teachings with the positions we are accustomed to ”3.

What positions of de Saussure were familiar to Russian linguists?

V.V. Vinogradov noted that "the future Saussurean difference between" langue "and" parole "[language and speech. - F. B.] found quite clear expression already in the 1870 lecture by Baudouin de Courtenay "Some" general remarks on linguistics and language. "3 According to Shcherba," the distinction between language as a system and language as an activity ( Saussure "a), not as clear and developed as in Saussure, characteristic of Baudouin." As for the distinction between synchronicity and diachrony, Shcherba noted that "the advancement of" synchronic linguistics "so characteristic of 4 Saussure ... is one of the foundations of all scientific activity of Baudouin> 4. Then this thesis of Baudouin de Courtenay was developed by his students, in particular by Bogoroditsky: “... The historicism of linguistic research can and should be supplemented by a synchronic comparison; the resulting synchronic series make it possible to determine the relative speed of movement of one or another phenomenon in individual languages "< >So, I put forward the idea of "synchronicity" in linguistic comparisons a whole quarter of a century before the appearance of "Cours de linguistique generale" (1916) by de Saussure, who had at his disposal ... my German brochure (Einige Reform-

1 Polivanov E. D. For Marxist linguistics. M., 1931, p. 3-4.

2 Shcherb and L.V. works on the Russian language. M., 1957, p. 94.

"Vinogradov V. I. A. Baudouin de Courtenay. - In the book: B o d u e n de

Courtenay I.A. works on general linguistics, t. 1. M., 1963, p. 12.4 Shcherba L.V. works on the Russian language, p. 94.

vorschlage ...), and if there is no mention of it in his book, then I explain this by the posthumous publication of his book, partly compiled from the notes of the listeners ”1.

In all likelihood, de Saussure was also familiar with the book by G. Paul "Principles of the History of Language", which distinguishes between individual speech and the common / language conditioned by the goals of communication, usus.

Back in 1870 Baudouin de Courtenay defined the content of external and internal linguistics. He pointed out that the external history of the language is closely "connected with the destinies of its speakers, the people, and the internal history of the language is concerned with the study of the life of the language in connection with the mental organization of the people speaking to them. Also later defines the tasks of external and internal linguistics and de Saussure.

At the same time, it should be pointed out that the problems of linguistics,

De Saussure solved in a new way, and this is his merit. First of all, he emphatically. ”Pointed out the social significance of a common language and the dependence of individual speech on it.

De Saussure understands language as a system, as a set of interacting and interdependent units. The problem of the consistency of a language lies at the heart of its linguistic theory. The merit of de Saussure is also that he drew the attention of linguists to the study of the internal laws of the language system.

Depending on which of the theoretical positions of de Saussure was taken as a basis, there are different assessments of his concept.

In his early work on the study of the vowel system in Indo-European languages, de Saussure explores the quantitative and qualitative relationships of vowels and sonorant sounds and reconstructs some of the disappeared sounds. In addition, he makes interesting observations about the structure of the Indo-European root. Subsequently, A. Meillet wrote that the study "On the original vowel system in Indo-European languages" played an outstanding role in the formation of a new method for analyzing the sound correspondences of related languages, therefore de Saussure can be called an outstanding Indo-Europeanist, the founder of modern comparative historical linguistics ...

Continuing this line of de Saussure's activity, a great contribution to the development of the comparative grammar of Indo-European languages / Viesley Meillet, Benveniste and E. Ku £ ilovich (in 1927 Kurilovich discovered _theoretical "predicted" by de "Saussure the sonantic coefficients in the newly discovered Hittite language and called them lariigal sounds).

De Saussure's assertion of the social character of language, the definition of language as a social phenomenon (albeit with a certain L psychological coloration of these concepts) gave rise to the

1 Bogoroditsk and V.A. Kazan, 1933, p. 154-155.

To declare de Saussure the founder of the sociological direction in linguistic knowledge. These provisions of de Saussure were developed subsequently by D ^ Meillet, JU. Balli and A. Seshe; they studied mainly the linguistics of speech. Balli "developed the foundations of linguistic stylistics J and created a theory of actualization of language signs in speech, and Sesche studied the problems of syntaxis. Among other representatives of the sociological trend "~ in French linguistics, F. Bruno, M. Grammont, A. Dose and J. Vandries should be mentioned.

And finally, there is a direct continuity between the positions of de Saussure and the representatives of structuralism in modern O. linguistics. Some structuralists (N. S. Trubetskoy) developed J de Saussure's doctrine of language and speech as applied to phonetics, others (L. Elmslev) focused on understanding language as a system of pure relations, behind which nothing real is hidden. The fact that European structuralism borrowed some of the general ideas of de Saussure served as the basis for recognizing de Saussure as the forerunner of structuralism.

1 See his work: French stylistics. M., 1961; General linguistics and questions of the French language. M., 1965.

| |

|

| Date of Birth | November 26(1857-11-26 ) |

| Place of Birth | |

| Date of death | February 22(1913-02-22 ) […] (55 years) |

| A place of death |

|

| Country | |

| Occupation | linguist |

| Father | Henri de Saussure |

| Children | Raymond de Saussure [d] and Jacques de Saussure[d] |

| Autograph |

|

| Ferdinand de Saussure at Wikimedia Commons | |

The main work of F. de Saussure - "Course of General Linguistics" (fr. Cours de linguistique générale).

"Course of General Linguistics"

A Course in General Linguistics was published posthumously in 1916 by Charles Bally and Albert Seschet based on Saussure's university lectures. Bally and Seschet may, to some extent, be considered co-authors of this work, since Saussure had no intention of publishing such a book, and much of its composition and content, apparently, was brought in by the publishers (much is not in Saussure's detailed lecture notes known to us, although of course he could share ideas with colleagues in private conversations).

One of the main provisions of the "Course of General Linguistics" is the distinction in speech activity (French langage) between language (French langue) and speech (French parole): “By separating language and speech, we thereby separate: 1) the social from the individual ; 2) essential from collateral and more or less accidental. " Language is a “function of the speaking subject”, “a product passively registered by an individual”, which “does not imply preliminary reflection”, and “analysis in it appears only in the area of classifying activity”. Speech is an “individual act of will and understanding”, containing, first, “combinations by which the speaking subject uses the linguistic code,” and secondly, a psychophysical mechanism that allows the subject to objectify these combinations; "There is nothing collective in speech." Speech activity "has a heterogeneous character," and language "is a phenomenon inherently homogeneous: it is a system of signs in which the only essential is the combination of meaning and an acoustic image."

Speech activity, a speech act, according to Saussure, has three components: physical (propagation of sound waves), physiological (from the ear to an acoustic image, or from an acoustic image to the movements of speech organs), mental (firstly, acoustic images are mental reality, not coinciding with the sound itself, a mental representation of the physical sound; secondly, concepts).

Although language does not exist outside the speech activity of individuals ("this is not an organism, this is not a plant that exists independently of a person, it does not have its own life, its own birth and death"), nevertheless, the study of speech activity should begin precisely with the study of language as the foundations of all phenomena of speech activity. Linguistics of language is the core of linguistics, linguistics "in the proper sense of the word."

In linguistics, the ideas of Ferdinand de Saussure stimulated the revision of traditional methods and, in the words of the famous American linguist Leonard Bloomfield, laid the "theoretical foundation for a new direction of linguistic research" - structural linguistics.

Having gone beyond the limits of linguistics, de Saussure's approach to language became the primary source of structuralism - one of the most influential trends in humanitarian thought in the 20th century. At the same time, he was the founder of the so-called sociological school in linguistics.

F. de Saussure was also an excellent teacher. During two decades of teaching at the University of Geneva, he brought up a whole galaxy of talented students who later became remarkable linguists (

By the beginning of the XX century. dissatisfaction not only with young grammatism, but, more broadly, with the entire comparative historical paradigm, has become widespread. The main task of linguistics in the 19th century. - the construction of comparative phonetics and comparative grammar of Indo-European languages was mainly solved by young grammarians (discoveries made at the beginning of the 20th century, first of all, the establishment by the Czech scientist B. Grozny that the Hittite language belongs to Indo-European languages, partially changed specific constructions, but did not affect the method and theory ). The time has not yet come for equally detailed reconstructions of other language families, since the process of collecting primary material has not been completed there. But it became more and more clear that the tasks of linguistics are not limited to the reconstruction of proto-languages and the construction of comparative phonetics and grammars. In particular, during the XIX century. the factual material at the disposal of scientists has significantly increased. In the above-mentioned compendium of the early 19th century. "Mithridates" mentioned about 500 languages, many of which were known only by name, and in the prepared in the 20s. XX century A. Meillet and his student M. Cohen of the encyclopedia "Languages of the World" have already recorded about two thousand languages. However, there was no developed scientific method to describe most of them, if only because their history was unknown. The "descriptive" linguistics, which was persecuted by the comparativists, did not go far in its methodology in comparison with the times of Port-Royal. At the beginning of the XX century. there are also complaints that linguistics is "divorced from life", "immersed in antiquity." Undoubtedly, the methods of comparative studies, polished by young grammarians, achieved perfection, but had limited applicability, and could not help in solving applied problems. Finally, as already mentioned, comparative studies have been constantly criticized for failing to explain the reasons for linguistic changes.

If in Germany, young grammatism continued to reign supreme throughout the first quarter of the 20th century, and its "dissidents" did not reject its main methodological principles, primarily the principle of historicism, then on the periphery of the then linguistic world from the end of the 19th century. more and more attempts were made to question the very methodological foundations of the prevailing linguistic paradigm of the 20th century. Such scientists included W. D. Whitney and F. Boas in the USA, G. Sweet in England and, of course, N. V. Krushevsky and I. A. Baudouin de Courtenay in Russia, discussed above. Opposition to comparativism as an all-encompassing methodology has always been particularly strong in France and, more broadly, in the culturally united Francophone countries, which also included the French-speaking parts of Switzerland and Belgium. Here the traditions of Port-Royal grammar never disappeared, interest in the study of the general properties of language, in universal theories, remained. It was here that the "Course of General Linguistics" by F. de Saussure appeared, which became the beginning of a new stage in the development of the world science of language.

Ferdinand de Saussure (1857–1913) lived an outwardly eventful life, but full of inner drama. He never had a chance to learn about the world resonance of his ideas, which he did not intend to publish during his lifetime and did not even have time to consistently state on paper.

F. de Saussure was born and raised in Geneva, the main cultural center of French Switzerland, into a family that has given the world several prominent scientists. From his youth he was interested in the general theory of language, however, in accordance with the traditions of his era, Indo-European studies became the specialization of the young scientist. In 1876-1878. he studied at the University of Leipzig, then the leading center shortly before this formed young grammatism; K. Brugman, G. Osthof, A. Leskin worked there at that time. Then, in 1878-1880, F. de Saussure trained in Berlin. The main work he wrote during his stay in Germany is the book "Memoir on the original vowel system in Indo-European languages", completed by the author at the age of 21. It was the only book by F. de Saussure published during his lifetime.