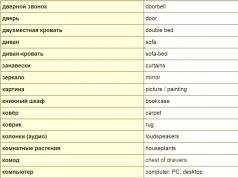

Prerequisites for the reforms of Peter the Great

Peter accepted Russia as a backward country, located on the outskirts of Europe. Muscovy did not have access to the sea, with the exception of the White, regular army, navy, developed industry, trade, system government controlled was antediluvian and inefficient, there were no higher educational institutions (only in 1687 the Slavic-Greek-Latin Academy opened in Moscow), printing, theater, painting, libraries, not only the people, but many members of the elite: boyars, nobles - did not know the letter . Science did not develop. Serfdom ruled.

Public Administration Reform

- Peter replaced the orders, which did not have clear responsibilities, with collegiums, the prototype of future ministries

- College of Foreign Affairs

- Collegium military

- Maritime College

- College for commercial affairs

- College of Justice...

The boards consisted of several officials, the eldest was called the chairman or president. All of them were subordinate to the Governor-General, who was a member of the Senate. There were 12 boards in total.

-

In March 1711, Peter created the Governing Senate. At first its function was to govern the country in the absence of the king, then it became a permanent institution. The Senate consisted of presidents of colleges and senators - people appointed by the king.

-

In January 1722, Peter issued a "table of ranks" with 14 class ranks from State Chancellor (first rank) to collegiate registrar (fourteenth)

-

Peter reorganized the secret police system. Since 1718, the Preobrazhensky Prikaz, which was in charge of political crimes, was transformed into the Secret Investigative Office

Church reform of Peter

Peter abolished the patriarchate, a church organization practically independent of the state, and instead created the Holy Synod, all members of which were appointed by the tsar, thereby eliminating the autonomy of the clergy. Peter pursued a policy of religious tolerance, facilitating the existence of the Old Believers and allowing foreigners to freely profess their faith.

Administrative reform of Peter

Russia was divided into provinces, provinces were divided into provinces, provinces into counties.

Provinces:

- Moscow

- Ingrian

- Kyiv

- Smolensk

- Azov

- Kazanskaya

- Arkhangelsk

- Siberian

- Riga

- Astrakhan

- Nizhny Novgorod

Military reform of Peter

Peter replaced the irregular and noble militia with a permanent regular army, completed with recruits, recruited one from each of the 20 peasant or petty-bourgeois households in the Great Russian provinces. He built a powerful navy, he wrote the military charter himself, taking the Swedish one as a basis.

Peter turned Russia into one of the strongest maritime powers in the world, with 48 linear and 788 galley and other ships

Economic reform of Peter

The modern army could not exist without a state supply system. To supply the army and navy with weapons, uniforms, food, consumables, it was necessary to create a powerful industrial production. By the end of Peter's reign, about 230 factories and plants operated in Russia. Factories focused on the production of glass products, gunpowder, paper, canvas, linen, cloth, paints, ropes, even hats were created, the metallurgical, sawmilling, and leather industries were organized. In order for the products of Russian masters to be competitive in the market, high customs duties for European goods. encouraging entrepreneurial activity, Peter widely used the issuance of loans to create new manufactories, trading companies. largest enterprises, which arose in the era of Peter's transformations, were created in Moscow, St. Petersburg, the Urals, Tula, Astrakhan, Arkhangelsk, Samara

- Admiralty Shipyard

- Arsenal

- Gunpowder factories

- Metallurgical plants

- Linen production

- Production of potash, sulfur, saltpeter

By the end of the reign of Peter I, Russia had 233 factories, including more than 90 large manufactories built during his reign. During the first quarter of the 18th century, 386 different ships were built at the shipyards of St. Petersburg and Arkhangelsk, at the beginning of the century, about 150 thousand pounds of pig iron were smelted in Russia, in 1725 - more than 800 thousand pounds, Russia caught up with England in iron smelting

Peter's reform in education

The army and navy needed qualified specialists. Therefore, Peter paid great attention to their preparation. During his reign were organized in Moscow and St. Petersburg

- School of Mathematical and Navigational Sciences

- artillery school

- engineering school

- medical school

- Marine Academy

- mining schools at the Olonets and Ural factories

- Digital schools for "children of every rank"

- Garrison schools for children of soldiers

- spiritual schools

- Academy of Sciences (opened a few months after the death of the emperor)

Reforms of Peter in the field of culture

- Publication of the first Russian newspaper "Sankt-Peterburgskie Vedomosti"

- Ban on boyars wearing beards

- Establishment of the first Russian museum - Kunskamera

- Requirement for nobility to wear European dress

- Creation of assemblies where the nobles were to appear together with their wives

- Creation of new printing houses and translation into Russian of many European books

Reforms of Peter the Great. Chronology

- 1690 - The first guards regiments Semenovsky and Preobrazhensky were created

- 1693 - Creation of a shipyard in Arkhangelsk

- 1696 - Creation of a shipyard in Voronezh

- 1696 - Decree on the establishment of an arms factory in Tobolsk

- 1698 - Decree banning the wearing of beards and ordering the nobles to wear European clothes

- 1699 - Dissolution of the archery army

- 1699 - creation of trade and industrial enterprises enjoying a monopoly

- 1699, December 15 - Decree on the reform of the calendar. New Year starts on January 1st

- 1700 - Creation of the Government Senate

- 1701 - Decree forbidding kneeling at the sight of the sovereign and taking off his hat in winter, passing by his palace

- 1701 - Opening of the school of mathematical and navigational sciences in Moscow

- 1703, January - the first Russian newspaper is published in Moscow

- 1704 - Replacement Boyar Duma Council of Ministers - Council of Chiefs of Orders

- 1705 - First recruitment decree

- 1708 November - Administrative Reform

- 1710, January 18 - decree on the official introduction of the Russian civil alphabet instead of Church Slavonic

- 1710 - Foundation of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra in St. Petersburg

- 1711 - instead of the Boyar Duma, a Senate of 9 members and a chief secretary was created. Monetary reform: minting gold, silver and copper coins

- 1712 - Transfer of the capital from Moscow to St. Petersburg

- 1712 - Decree on the creation of horse breeding farms in the Kazan, Azov and Kyiv provinces

- 1714, February - Decree on the opening of digital schools for the children of clerks and priests

- 1714, March 23 - Decree on majorate (single inheritance)

- 1714 - Foundation of the State Library in St. Petersburg

- 1715 - Creation of shelters for the poor in all cities of Russia

- 1715 - Order of the merchant college to organize the training of Russian merchants abroad

- 1715 - Decree to encourage the cultivation of flax, hemp, tobacco, mulberries for silkworms

- 1716 - Census of all dissenters for double taxation

- 1716, March 30 - Adoption of military regulations

- 1717 - The introduction of free trade in grain, the annulment of some privileges for foreign merchants

- 1718 - Replacement of Orders by Colleges

- 1718 - Judicial reform. tax reform

- 1718 - Beginning of the census (lasted until 1721)

- 1719, November 26 - Decree on the establishment of assemblies - free meetings for fun and business

- 1719 - Creation engineering school, the establishment of the Berg College for the management of the mining industry

- 1720 - Adopted the Charter of the Sea

- 1721, January 14 - Decree on the creation of the Spiritual College (future Holy Synod)

The era of Peter the Great in the life of the Russian Church is full of historical content. First, both the relation of the church to the state and the church government became clear and took on new forms. Secondly, the internal church life was marked by a struggle of theological views (for example, the familiar dispute about transubstantiation between the Great Russian and Little Russian clergy and other disagreements). Thirdly, the literary activity of the representatives of the church revived. In our presentation, we will touch only on the first of these points, because the second has a special church-historical interest, and the third is considered in the history of literature.

Consider first those measures of Peter I, which established the relationship of church to state and the general order of church government; then we will move on to particular measures regarding ecclesiastical affairs and the clergy.

The relationship of church to state before Peter I in the Muscovite state was not precisely defined, although at the church council of 1666-1667. The Greeks recognized in principle the supremacy of secular power and denied the right of hierarchs to interfere in secular affairs. The Moscow sovereign was considered the supreme patron of the church and took an active part in church affairs. But church authorities were also called upon to participate in state administration and influenced it. Russia did not know the struggle between church and secular authorities, familiar to the West (it did not exist, strictly speaking, even under Nikon). The enormous moral authority of the Moscow patriarchs did not seek to replace the authority state power, and if a voice of protest was heard from the side of the Russian hierarch (for example, Metropolitan Philip against Ivan IV), then he never left the moral ground.

Peter I did not grow up under the strong influence of theological science and not in such a pious environment as his brothers and sisters grew up. From the very first steps conscious life he made friends with the "heretic Germans" and, although he remained an Orthodox person by conviction, he nevertheless treated many rituals more freely than ordinary Moscow people, and seemed infected with "heresy" in the eyes of the Old Testament zealots of piety. It can be said with confidence that Peter, from his mother and from the conservative patriarch Joachim (d. 1690), more than once met with condemnation for his habits and acquaintance with heretics. Under Patriarch Adrian (1690-1700), a weak and timid man, Peter met with no more sympathy for his innovations, following Joachim and Adrian, he forbade barbering, and Peter thought to make it obligatory. At the first decisive innovations of Peter, all those who protested against them, seeing them as heresy, sought moral support in the authority of the church and were indignant at Adrian, who was cowardly silent, in their opinion, when he should have stood for orthodoxy. Adrian really did not interfere with Peter and was silent, but he did not sympathize with the reforms, and his silence, in essence, was a passive form of opposition. Insignificant in itself, the patriarch became inconvenient for Peter, as the center and unifying principle of all protests, as a natural representative of not only ecclesiastical, but also social conservatism. The patriarch, strong in will and spirit, could have been a powerful opponent of Peter I if he had taken the side of the conservative Moscow worldview, which condemned all public life to immobility.

Realizing this danger, after the death of Adrian, Peter was in no hurry to elect a new patriarch, and appointed Ryazan Metropolitan Stefan Yavorsky, a learned Little Russian, as the "locum tenens of the patriarchal throne." The management of the patriarchal economy passed into the hands of specially appointed secular persons. There is no need to assume, as some do, that immediately after the death of Hadrian, Peter decided to abolish the patriarchate. It would be more correct to think that Peter simply did not know what to do with the election of a patriarch. Peter treated the Great Russian clergy with some distrust, because he was convinced many times how strongly they did not sympathize with the reforms. Even the best representatives of the ancient Russian hierarchy, who managed to understand the entire nationality foreign policy Peter I and helped him as best they could (Mitrofan of Voronezh, Tikhon of Kazan, Job of Novgorod), and they were against the cultural innovations of Peter. To choose a patriarch from among the Great Russians for Peter meant the risk of creating a formidable opponent for himself. The Little Russian clergy behaved differently: they themselves were influenced by Western culture and science and sympathized with the innovations of Peter I. But it was impossible to appoint a Little Russian patriarch because during the time of Patriarch Joachim, Little Russian theologians were compromised in the eyes of Moscow society, as people with Latin delusions; for this they were even persecuted. The elevation of a Little Russian to the patriarchal throne would therefore lead to a general temptation. In such circumstances, Peter I decided to remain without a patriarch.

The following order of church administration was temporarily established: at the head of the church administration were locum tenens Stefan Yavorsky and a special institution, the Monastery Order, with secular persons at the head; the council of hierarchs was recognized as the supreme authority in matters of religion; Peter himself, like the former sovereigns, was the patron of the church and took an active part in its management. This participation of Peter led to the fact that in the church life an important role began to play the bishops of the Little Russians, who had been persecuted before. Despite protests both in Russia and in the Orthodox East, Peter constantly nominated Little Russian learned monks to the episcopal chairs. The Great Russian clergy, poorly educated and hostile to the reform, could not be an assistant to Peter I, while the Little Russians, who had a broader mental outlook and grew up in a country where Orthodoxy was forced into an active struggle against Catholicism, brought up in themselves a better understanding of the tasks of the clergy and the habit of broad activities. In their dioceses, they did not sit idly by, but converted foreigners to Orthodoxy, acted against the schism, started schools, took care of the life and morality of the clergy, and found time for literary activity. It is clear that they were more in line with the wishes of the reformer, and Peter I valued them more than those clergy from the Great Russians, whose narrow views often got in his way. One can cite a long series of names of Little Russian bishops who occupied prominent places in the Russian hierarchy. But the most remarkable of them are: Stefan Yavorsky, mentioned above, St. Dmitry, Metropolitan of Rostov and, finally, under Peter, Bishop of Pskov, later Archbishop of Novgorod. He was a very capable, lively and energetic person, inclined to practical activity much more than to abstract science, but he was very educated and studied theological science not only at the Kyiv Academy, but also in the Catholic colleges of Lvov, Krakow and even Rome. The scholastic theology of Catholic schools did not affect Theophan's living mind, on the contrary, it planted in him a dislike for scholasticism and Catholicism. Not getting satisfaction in Orthodox theological science, then poorly and little developed, Theophanes turned from Catholic doctrines to the study of Protestant theology and, being carried away by it, learned some Protestant views, although he was an Orthodox monk. This inclination towards the Protestant worldview, on the one hand, was reflected in Theophan's theological treatises, and on the other hand, helped him get closer to Peter I in his views on reform. The king, brought up in Protestant culture, and the monk, who completed his education in Protestant theology, understood each other perfectly. Acquainted with Feofan for the first time in Kyiv in 1706, Peter in 1716 summoned him to St. Petersburg, made him his right hand in the matter of church administration and defended against all attacks from other clergy, who noticed the Protestant spirit in Peter's favorite. Theophanes, in his famous sermons, was an interpreter and apologist for Peter's reforms, and in his practical activities he was a sincere and capable assistant to him.

It was Feofan who developed and, perhaps, even the very idea of that new plan of church administration, on which Peter I stopped. For more than twenty years (1700-1721) a temporary disorder continued, in which the Russian church was governed without a patriarch. Finally, on February 14, 1721, the "Holy Governing Synod" was opened. This spiritual college forever replaced the patriarchal authority. She was given the Spiritual Regulations, compiled by Feofan and edited by Peter I himself, as her guide. The regulations frankly pointed out the imperfection of the patriarch's sole administration and the political inconveniences resulting from the exaggeration of the authority of the patriarchal authority in state affairs. The collegial form of church government was recommended as the best in all respects. According to the regulations, the composition of the Synod is defined as follows: the president, two vice-presidents, four advisers and four assessors (they included representatives of the black and white clergy). Note that the composition of the Synod was similar to that of the secular boards. The persons who were at the Synod were the same as at the colleges; the representative of the person of the sovereign in the Synod was the Chief Procurator, under the Synod there was also a whole department of fiscals, or inquisitors. The external organization of the Synod was, in a word, taken from the general type of organization of the collegium.

Speaking about the position of the Synod in the state, one should strictly distinguish its role in the sphere of the church from its role in common system government controlled. The significance of the Synod in church life is clearly defined by the Spiritual Regulations, according to which the Synod has "the power and authority of the patriarch." All spheres of jurisdiction and all the fullness of the ecclesiastical authority of the patriarch are inherent in the Synod. The diocese of the patriarch, which was under his personal control, was also transferred to him. This diocese was administered by the Synod through a special collegium called a dicastery or consistory. (According to the model of this consistory, consistories were gradually organized in the dioceses of all bishops). Thus, in church affairs, the Synod completely replaced the patriarch.

But in the sphere of public administration, the Synod did not fully inherit the patriarchal authority. We have various opinions about the significance of the Synod in the general composition of the administration under Peter. Some believe that "the Synod was in everything compared with the Senate and, along with it, was directly subordinate to the sovereign" (such an opinion is held, for example, by P. Znamensky in his "Guide to Russian Church History"). Others think that under Peter, in practice, the state significance of the Synod became lower than that of the Senate. Although the Synod strives to become independent of the Senate, the latter, considering the Synod as an ordinary collegium for spiritual affairs, considered it subordinate to itself. Such a view of the Senate was justified by the general idea of the reformer, which was the basis of the church reform: with the establishment of the Synod, the church became dependent not on the person of the sovereign, as before, but on the state, its management was introduced into the general administrative order and the Senate, which managed the affairs of the church until the establishment of the Synod , could consider himself higher than the Theological College, as the supreme administrative body in the state (such a view was expressed in one of the articles by Professor Vladimirsky-Budanov). It is difficult to decide which opinion is fairer. One thing is clear that political significance The Synod never rose as high as the authority of the patriarchs (on the beginning of the Synod, see P. V. Verkhovsky "The Establishment of the Spiritual College and the Spiritual Regulations", two volumes. 1916; also G. S. Runkevich "The Establishment and Initial Organization of St. Pr. Synod", 1900).

Thus, by establishing the Synod, Peter I got out of the difficulty in which he had stood for many years. His church-administrative reform preserved authoritative power in the Russian church, but deprived this power of the political influence with which the patriarchs could act. The question of the relationship between church and state was decided in favor of the latter, and the eastern hierarchs recognized the replacement of the patriarch by the Synod as completely legitimate. But these same Eastern Greek hierarchs under Tsar Alexei had already resolved in principle the same question and in the same direction. Therefore, Peter's church transformations, being a sharp novelty in their form, were built on the old principle bequeathed to Peter by Moscow Russia. And here, as in other reforms of Peter I, we meet with the continuity of historical traditions.

As for private events for church and faith in the era of Peter I, we can only briefly mention the most important of them, namely: the church court and land ownership, the black and white clergy, the attitude towards non-believers and schism.

Church jurisdiction was very limited under Peter: a lot of cases from church courts moved to secular courts (even a trial of crimes against faith and the church could not be carried out without the participation of secular authorities). For the trial of church people, according to the claims of secular persons, the Monastic order with secular courts was restored in 1701 (closed in 1677). In such a limitation of the judicial function of the clergy, one can see a close connection with the measures of the Code of 1649, in which the same trend affected.

The same close connection with ancient Russia can be seen in the measures of Peter I regarding real estate church property. The land estates of the clergy under Peter were first subjected to strict state control, and subsequently were withdrawn from economic management clergy. Their management was transferred to the Monastic order; they turned, as it were, into state property, part of the income from which went to the maintenance of monasteries and lords. This is how Peter tried to resolve the age-old question of the land holdings of the clergy in Russia. At the turn of the XV and XVI centuries. the right of monasteries to own estates was denied by a part of monasticism itself (Nil of Sora); to late XVI in. the government drew attention to the rapid alienation of land from the hands of service people into the hands of the clergy and sought to, if not completely stop, then limit this alienation. In the 17th century Zemstvo petitions insistently pointed out the harm of such alienation for the state and the noble class; the state was losing lands and duties from them; nobles became landless. In 1649, a law finally appeared in the Code, which forbade the clergy from further acquisition of land. But the Code has not yet decided to return to the state those lands owned by the clergy.

Concerned about raising morality and well-being among the clergy, Peter special attention He referred to the life of the white clergy, poor and poorly educated, "nothing from arable peasants, indispensable," in the words of a contemporary. Alongside his decrees, Peter tried to cleanse the milieu of the clergy by forcibly diverting its superfluous members to other estates and occupations and persecuting its bad elements (the wandering clergy). At the same time, Peter tried to better provide the parish clergy by reducing their number and increasing the area of parishes. He thought to raise the morality of the clergy by education and strict control. However, all these measures did not give great results.

Peter I treated monasticism not only with less care, but even with some enmity. It proceeded from the conviction of Peter that the monks were one of the causes of popular dissatisfaction with the reform and stood in opposition. A man with a practical orientation, Peter poorly understood the meaning of contemporary monasticism and thought that the majority became monks "from taxes and from laziness in order to eat bread for nothing." Not working, the monks, according to Peter, "eat up other people's works" and in inaction breed heresies and superstitions and do not do their job: excite the people against innovations. With such a view of Peter I, it is understandable his desire to reduce the number of monasteries and monks, to strictly supervise them and limit their rights and benefits. The monasteries were deprived of their lands, their income, and the number of monks was limited by the states; not only vagrancy, but also the transition from one monastery to another was prohibited, the personality of each monk was placed under the strict control of the abbots: writing in cells was prohibited, communication between monks and laity was difficult. At the end of his reign, Peter I expressed his views on the social significance of monasteries in the "Announcement of Monasticism" (1724). According to this view, monasteries should have a charitable purpose (the poor, sick, disabled and wounded were placed in monasteries), and in addition, monasteries should have served to prepare people for higher spiritual positions and to provide shelter to people who are inclined to a pious contemplative life. . With all his activities regarding monasteries, Peter I strove to bring them into line with the indicated goals.

In the era of Peter I, the attitude of the government and the church towards the Gentiles became softer than it was in the 17th century. Western Europeans were treated with tolerance, but even under Peter the Protestants were favored more than the Catholics. Peter's attitude towards the latter was conditioned not only by religious motives, but also by political ones: Peter I responded to the oppression of the Orthodox in Poland by threatening to persecute the Catholics. But in 1721, the Synod issued an important decree on the admission of marriages between Orthodox and non-Orthodox - and with Protestants and Catholics alike.

Political motives were partly guided by Peter in relation to the Russian schism. While he saw the schism as an exclusively religious sect, he treated it rather mildly, without touching the beliefs of the schismatics (although from 1714 he ordered them to take a double taxable salary). But when he saw that the religious conservatism of the schismatics leads to civil conservatism and that the schismatics are sharp opponents of his civic activities, then Peter changed his attitude towards the schism. In the second half of the reign of Peter I, repressions went along with religious tolerance: schismatics were persecuted as civil opponents of the ruling church; at the end of the reign, religious tolerance seemed to have diminished, and the civil rights of all schismatics, without exception, involved and not involved in political affairs, were restricted. In 1722, the schismatics were even given a certain attire, in the features of which there was, as it were, a mockery of the schism.

Speaking briefly about the course of the church reform of Peter I, it is important to note its thoughtfulness. At the end of the reform, Russia, as a result, received only one person with absolute full power.

Church reform of Peter I

From 1701 to 1722, Peter the Great tried to reduce the authority of the Church and establish control over its administrative and financial activities. The prerequisites for this was the protest of the Church against the changes taking place in the country, calling the king the Antichrist. Possessing enormous authority, comparable to the authority and fullness of power of Peter himself, the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia was the main political competitor of the Russian tsar-reformer.

Rice. 1. Young Peter.

Among other things, the Church had accumulated enormous wealth, which Peter needed to wage war with the Swedes. All this tied the hands of Peter to use all the resources of the country for the sake of the desired victory.

The tsar was faced with the task of eliminating the economic and administrative autonomy of the Church and reducing the number of the clergy.

Table “The essence of the ongoing reforms”

|

Developments |

Year |

Goals |

|

|

Appointment of the "Guardian and Steward of the Patriarchal Throne" |

Replace the election of the Patriarch by the Church with an imperial appointment |

Peter personally appointed the new Patriarch |

|

|

Secularization of peasants and lands |

The elimination of the financial autonomy of the Church |

Church peasants and lands were transferred to the management of the State. |

|

|

Monastic prohibitions |

Reduce the number of priests |

You can not build new monasteries and conduct a census of monks |

|

|

Senate control of the Church |

Restriction of the administrative freedom of the Church |

The creation of the Senate and the transfer of church affairs to its management |

|

|

Decree on the limitation of the number of clergy |

Improving the efficiency of human resource allocation |

Ministers are attached to a particular parish, they are forbidden to travel |

|

|

The preparatory stage for the abolition of the Patriarchate |

Get full power in the empire |

Development of a project for the establishment of the Spiritual College |

January 25, 1721 is the date of the final victory of the emperor over the patriarch, when the patriarchate was abolished.

TOP 4 articleswho read along with this

Rice. 2. Prosecutor General Yaguzhinsky.

The relevance of the topic was not only under Peter, but also under the Bolsheviks, when not only church authority was abolished, but also the very structure and organization of the Church.

Rice. 3. The building of 12 colleges.

The Spiritual Board had another name - the Governing Synod. A secular official, not a clergyman, was appointed to the position of chief prosecutor of the Synod.

As a result, the reform of the Church of Peter the Great had its pros and cons. Thus, Peter discovered for himself the possibility of leading the country towards Europeanization, but in cases where this power was abused, Russia could end up in a dictatorial and despotic regime in the hands of another person. However, the consequences are a reduction in the role of the church in the life of society, a reduction in its financial independence and the number of servants of the Lord.

Gradually, all institutions began to concentrate around St. Petersburg, including church ones. The activities of the Synod were monitored by the fiscal services.

Peter also introduced church schools. According to his plan, every bishop was obliged to have a school for children at home or at home and provide primary education.

Results of the reform

- The post of Patriarch was liquidated;

- Increased taxes;

- Recruitment sets from church peasants are conducted;

- Reduced the number of monks and monasteries;

- The church is dependent on the emperor.

What have we learned?

Peter the Great concentrated all branches of power in his hands and had unlimited freedom of action, establishing absolutism in Russia.

Topic quiz

Report Evaluation

average rating: 4.6. Total ratings received: 228.

Social (estate) reforms of Peter I - briefly

As a result of the social reforms of Peter I, the position of the three main Russian estates - nobles, peasants and urban residents - has changed dramatically.

service estate, nobles , after the reforms of Peter I, they began to perform military service not with local militias recruited by them themselves, but in regular regiments. The service of the nobles now (in theory) began with the same lower ranks as the common people. Natives of non-noble estates, on a par with the nobles, could rise to the very high ranks. The order of passing official degrees was determined from the time of the reforms of Peter I, no longer by generosity and not by customs like localism, but published in 1722 " Table of ranks". She established 14 ranks of the army and civilian service.

To prepare for the service, Peter I also obliged the nobles to undergo initial training in literacy, numbers and geometry. A nobleman who did not pass the established exam was deprived of the right to marry and receive an officer's rank.

It should be noted that the landlord class, even after the reforms of Peter I, still had quite important service advantages over the ignoble people. Applicants for military service nobles, as a rule, were ranked not as ordinary army regiments, but as privileged guards - Preobrazhensky and Semenovsky, quartered in St. Petersburg.

major social change peasants was associated with the tax reform of Peter I. It was carried out in 1718 and replaced the previous homestead(from each peasant household) method of taxation per capita(from the heart). According to the results of the 1718 census, poll tax.

This purely financial, at first glance, reform had, however, an important social content. The new poll tax was ordered to be equally collected not only from the peasants, but also from the privately owned serfs who had not previously paid state taxes. This prescription of Peter I brought the social position of the peasantry closer to that of the disenfranchised servile. It predetermined the evolution of the view of serfs to late XVIII century is not like sovereign heavy people(which they were considered before), but how on complete master's slaves.

Cities : the reforms of Peter I aimed to arrange city government according to European models. In 1699, Peter I granted Russian cities the right to self-government in the person of elected Burmisters, which were to be town hall. The townspeople were now divided into "regular" and "irregular", as well as into guilds and workshops by occupation. By the end of the reign of Peter I, the town halls were transformed into magistrates, which had more rights than town halls, but were elected in a less democratic way - only from "first-class" citizens. At the head of all the magistrates was (since 1720) the Metropolitan Chief Magistrate, who was considered a special collegium.

Peter I. Portrait by P. Delaroche, 1838

Military reform of Peter I - briefly

Administrative and state reforms of Peter I - briefly

Financial reforms of Peter I - briefly

Economic reforms of Peter I - briefly

Like most European figures of the second half of XVII – early XVIII century Peter I followed in economic policy principles of mercantilism. Applying them to life, he tried in every possible way to develop industry, built factories with state funds, encouraged such construction by private entrepreneurs through broad benefits, attributed serfs to factories and manufactories. By the end of the reign of Peter I, there were already 233 factories in Russia.

In foreign trade the mercantilist policy of Peter I led to strict protectionism (high duties were imposed on imported products to prevent them from competing with Russian products). Widely used state regulation economy. Peter I contributed to the laying of canals, roads and other means of communication, the exploration of minerals. Powerful push Russian economy gave the development of the mineral wealth of the Urals.

Church reform of Peter I - briefly

As a result of the church reform of Peter I, the Russian church, which had previously been quite independent, became completely dependent on the state. After the death of Patriarch Adrian (1700), the king prescribed not elect new patriarch, and the Russian clergy then did not have him until the council of 1917. Instead was appointed king"locum tenens of the patriarchal throne" - Ukrainian Stefan Yavorsky.

This "uncertain" state of affairs persisted until the final reform of church administration was carried out in 1721, developed with the active participation of Feofan Prokopovich. According to this church reform of Peter I, the patriarchate was finally abolished and replaced by a "spiritual college" - Holy Synod. Its members were not elected by the clergy, but appointed by the tsar - the church has now legally become completely dependent on the secular authorities.

In 1701 the church's land holdings were transferred to the control of the secular Monastic order. After the synodal reform of 1721, they were formally returned to the clergy, but since the latter now completely submitted to the state, this return was of little importance. Peter the Great also placed monasteries under strict state control.

The position of the Russian Church before the reforms of Peter I

It is noteworthy that throughout the preparation of the reform of church administration, Peter was in intensive relations with eastern patriarchs- First of all, by Patriarch Dositheus of Jerusalem - on various issues of both spiritual and political nature. And he also addressed the Ecumenical Patriarch Kosma with private spiritual requests, somehow permission for him to “eat meat” during all fasts; his Letter to the Patriarch dated July 4, 1715 justifies the request by the fact that, as the document says, “I suffer from febro and sorbutina, which illnesses happen to me more from all sorts of harsh foods, and especially more gently forced to be unceasingly for the defense of the holy church and state and my subjects in military difficult and distant campaigns<...>» . By another letter of the same day, he asks Patriarch Kosma for permission to eat meat in all positions throughout the Russian army during military campaigns, " “before our Orthodox troops<...>there are hard and long campaigns and remote and uncomfortable and deserted places, where there is little, and sometimes nothing is found, no fish, below some other lenten dishes, and often even bread itself ”. Undoubtedly, it was more convenient for Peter to resolve issues of a spiritual nature with the eastern patriarchs, who were largely supported by the Moscow government (and Patriarch Dositheus was de facto a political agent and informer for several decades Russian government about everything that happened in Constantinople), rather than with their own, sometimes obstinate, clergy.

The first undertakings of Peter in this area

Patriarch Adrian.

The position of the head of the Russian clergy became even more difficult when, from 1711, instead of the old Boyar Duma, the Governing Senate began to operate. According to the decree on the establishment of the Senate, all administrations, both spiritual and secular, were to obey the decrees of the Senate as royal decrees. The Senate immediately seized the supremacy in spiritual administration. Since 1711, the guardian of the patriarchal throne cannot appoint a bishop without the Senate. The Senate independently builds churches in the conquered lands and itself orders the Pskov ruler to put priests there. The Senate assigns abbots and abbesses to monasteries, disabled soldiers send their requests to the Senate for permission to settle in a monastery.

Further, the regulations indicate historical examples of what the clergy's lust for power led to in Byzantium and in other states. Therefore, the Synod soon became an obedient tool in the hands of the sovereign.

The composition of the Holy Synod was determined according to the regulations in 12 "governing persons", of which three certainly had to bear the rank of bishop. As in the civil colleges, the Synod counted one president, two vice-presidents, four councilors and five assessors. In the year, these foreign titles, which did not fit in so well with the spiritual orders of the persons sitting in the Synod, were replaced by the words: first-present member, members of the Synod and those present in the Synod. According to the regulations, the President, who is subsequently first present, has a voice equal to that of the other members of the board.

Before entering into the position assigned to him, each member of the Synod, or, according to the regulations, "every collegiate, like the president, and others", should be “make an oath or promise before St. Evangelism", where "under the personal penalty of anathema and corporal punishment" promised “seek always the very essence of truth and the very essence of truth” and do everything “according to the charters written in the spiritual regulations and henceforth able to follow additional definitions to them”. Together with the oath of fidelity to serve their cause, the members of the Synod swore allegiance to the service of the reigning sovereign and his successors, pledged to inform in advance about the damage to His Majesty's interest, harm, loss, and in conclusion, they were supposed to swear "to confess to the last judge of the spiritual sowing colleges, to be the most all-Russian monarch". The end of this oath, compiled by Feofan Prokopovich and corrected by Peter, is extremely significant: “I also swear by the all-seeing God that all this that I now promise does not interpret differently in my mind, as if I prophesy with my mouth, but in that power and mind, the words written here are read and heard by such power and mind”.

Metropolitan Stefan was appointed President of the Synod. In the Synod, he somehow immediately turned out to be a stranger, despite his presidency. During the whole year Stefan visited the Synod only 20 times. He had no influence on the affairs.

A man who was unconditionally devoted to Peter, Theodosius, the bishop of the Alexander Nevsky Monastery, was appointed vice-president.

In terms of the structure of the office and office work, the Synod resembled the Senate and collegiums, with all the ranks and customs established in these institutions. Just as there, Peter took care of the organization of supervision over the activities of the Synod. On May 11, the special Chief Procurator was ordered to be present in the Synod. Colonel Ivan Vasilyevich Boltin was appointed the first Chief Procurator of the Synod. The main duty of the chief prosecutor was to conduct all relations between the Synod and the civil authorities and vote against the decisions of the Synod when they were not consistent with the laws and decrees of Peter. The Senate gave the Chief Prosecutor a special instruction, which was almost a complete copy of the instruction to the Prosecutor General of the Senate.

Just like the Prosecutor General, the Chief Prosecutor of the Synod is called an instruction "with the eye of the sovereign and the solicitor on state affairs". The chief procurator was subject to the court only of the sovereign. At first, the power of the chief prosecutor was exclusively observant, but little by little the chief prosecutor becomes the arbiter of the fate of the Synod and its leader in practice.

As in the Senate, near the position of the prosecutor, there were fiscals, so in the Synod, spiritual fiscals, called inquisitors, were appointed, with an arch-inquisitor at the head. The inquisitors were supposed to secretly supervise the correct and lawful course of the affairs of church life. The office of the Synod was organized on the model of the Senate and was also subordinate to the Chief Procurator. In order to create a living connection with the Senate, the position of an agent was established under the Synod, whose duty, according to the instructions given to him, was “recommend both in the Senate and in the collegiums and in the office urgently, so that, according to these synodal decrees and decrees, the proper dispatch would be done without a continuation of time”. Then the agent made sure that the synodal messages sent to the Senate and collegiums were heard before other matters, otherwise he had to "protest to the persons in charge there" and inform the prosecutor general. Important papers that came from the Synod to the Senate, the agent had to carry himself. In addition to the agent, the Synod also had a commissar from the Monastic order, who was in charge of the frequent and extensive in its volume and significance of the relations of this order with the Synod. His position was in many ways reminiscent of the position of commissars from the provinces under the Senate. For the convenience of managing the affairs to be administered by the Synod, they were divided into four parts, or offices: the office of schools and printing houses, the office of judicial affairs, the office of schismatic affairs and the office of inquisitorial affairs.

The new institution, according to Peter, should immediately take up the correction of vices in church life. The Spiritual Regulations indicated the tasks of the new institution and noted those shortcomings in the church structure and way of life, with which it was necessary to begin a decisive struggle.

All matters subject to the conduct of the Holy Synod, the Regulations divided into general ones, relating to all members of the Church, that is, both secular and spiritual, and into “own” affairs, relating only to the clergy, white and black, to theological school and enlightenment. Defining the general affairs of the Synod, the regulations impose on the Synod the obligation to ensure that among the Orthodox all “It was done right according to Christian law” so that there is nothing contrary to this "law", and not to be "poorness in the instruction that is fitting for every Christian". The regulation enumerates, monitor the correctness of the text of the sacred books. The synod was supposed to eradicate superstition, establish the authenticity of the miracles of newly-appeared icons and relics, observe the order of church services and their correctness, protect faith from the harmful influence of false teachings, for which it hoped to have the right to judge schismatics and heretics and to have censorship over all the "history of the saints" and any kind of theological writings, observing that nothing contrary to the Orthodox dogma should pass. The Synod, on the other hand, has the categorical permission "perplexed" cases of pastoral practice in matters of Christian faith and virtue.

In terms of enlightenment and education, the Spiritual Regulations instructed the Synod to ensure that “We were satisfied with the correction of Christian teaching”, for which it is necessary to make short and easy-to-understand for ordinary people books for teaching the people the most important dogmas of faith and the rules of Christian life.

In the matter of governing the church system, the Synod had to examine the dignity of persons appointed to the hierarchs; to protect the church clergy from insults from outside "secular gentlemen who have a command"; see that every Christian stays in his calling. The synod was obliged to instruct and punish those who erred; Bishops must watch “Are not priests and deacons outrageous, are drunks noisy in the streets, or, worse, in churches are they quarreling like a man”. Concerning the bishops themselves, it was prescribed: “to tame this great cruel bishops’ glory, so that under their arms, while they are healthy, it’s not driven, and the assistant brethren would not bow to the ground with them”.

All cases that had previously been subject to the patriarchal court were subject to the Synod's court. As far as church property is concerned, the Synod must look after the correct use and distribution of church property.

With regard to its own affairs, the Rules note that, in order to properly perform its task, the Synod must know what the duties of each member of the Church are, that is, bishops, presbyters, deacons and other clergymen, monks, teachers, preachers, and then devotes a lot of space to the affairs of bishops, the affairs educational and enlightening and the duties of the laity in relation to the Church. The affairs of other church clergy and concerning monks and monasteries were detailed somewhat later in a special "Addendum to the Spiritual Regulations."

This addition was compiled by the Synod itself and sealed to the Spiritual Regulations without the knowledge of the tsar.

Measures to restrict white clergy

Under Peter, the clergy began to turn into the same estate, having state tasks, their rights and obligations, like the gentry and townspeople. Peter wanted the clergy to become an organ of religious and moral influence on the people, at the full disposal of the state. Through the creation of the highest church administration - the Synod - Peter received the opportunity of supreme control over church affairs. The formation of other estates - the gentry, townspeople and peasants - already quite definitely limited those who belonged to the clergy. A number of measures regarding the white clergy were meant to further clarify this limitation of the new estate.

In Ancient Russia, access to the clergy was widely open to everyone, and the clergy were not bound by any restrictive regulations: each clergyman could remain or not remain in a clergy, freely move from city to city, from serving in one church to another; the children of clerics were also in no way connected by their origin and could choose whatever field of activity they wanted. In the 17th century, even people who were not free could enter the clergy, and the landowners of that time often had priests from people who were strong for them. They were willing to join the clergy, because here it was more possible to find a job and it was easier to avoid taxes. The lower parish clergy were then selective. The parishioners, as a rule, chose from among themselves, as it seemed to them, a person suitable for the priesthood, gave him a letter of choice and sent him to be "appointed" to the local bishop.

The Muscovite government, protecting the state's payment forces from decline, long ago began to instruct cities and villages to elect children or relatives of deceased clergymen to the depleted priestly and deacon places, counting that such persons are more prepared for the priesthood than "rural ignoramuses". Communities, in whose interests it was also not to lose unnecessary co-payers, themselves tried to choose their pastors from spiritual families known to them. By the 17th century, this was already a custom, and the children of clergy, although they can enter any rank through service, prefer to wait in line to take a spiritual place. Therefore, the church clergy turned out to be extremely overcrowded with children of the clergy, old and young, waiting for a “place”, but for the time being, staying with the fathers and grandfathers of the priests as sexton, bell ringers, deacons, etc. In the year, the Synod was informed that at some Yaroslavl churches there were so many priestly children, brothers, nephews, grandchildren in clerical places, that there were almost fifteen of them for five priests.

As in the 17th century, so under Peter there were very rare parishes where only one priest was listed - in most there were two and three. There were such parishes where, with fifteen households of parishioners, there were two priests with a dark, wooden, dilapidated little church. With rich churches, the number of priests reached six or more.

The comparative ease of obtaining the dignity created in ancient Russia a wandering priesthood, the so-called "sacral". The sacraments were called in old Moscow and other cities the places of intersection big streets where there were always a lot of people. In Moscow, the Barbarian and Spassky sacraments were especially famous. The clergy who left their parishes for free trade as a priest and deacon mostly gathered here. Some mourner, rector of the church with the arrival of two or three yards, of course, could earn more by offering his services to those who wanted to serve a prayer service at home, celebrate magpie in the house, bless the memorial meal. All those who needed a priest went to the sacrum and here they chose who they wanted. It was easy to get a leave letter from the bishop, even if the bishop was against it: such profitable business was not brought to him by the bishop's servants, eager for bribes and promises. In Moscow during the time of Peter the Great, even after the first revision, after many measures aimed at the destruction of the sacral clergy, there were more than 150 registered priests who signed up for the order of church affairs and paid stole money.

Of course, the existence of such a wandering clergy, with the government striving to enlist everything and everyone in the state for “service”, could not be tolerated, and Peter, back in the early 1700s, made a number of orders restricting the freedom to enter the clergy. In the year, these measures are somewhat systematized and confirmed, and an explanation of the measures to reduce the spiritual rank follows: from its spread "the state service in its needs was felt to be diminished". In the year Peter issued an order to the bishops to “they did not multiply priests and deacons for the sake of profit, lower for heritage”. The exit from the clergy was facilitated, and Peter favorably looked at the priests who left the clergy, but also at the Synod itself. Simultaneously with concerns about the quantitative reduction of the spiritual rank, Peter's government is concerned about attaching it to the places of service. The issuance of passable letters is at first very difficult, and then completely stops, and moreover, secular persons are strictly forbidden, under fines and punishment, to accept priests and deacons for the fulfillment of the requirement. One of the measures to reduce the number of clergy was the prohibition to build new churches. Bishops, accepting the chair, had to give an oath promise that “neither will they themselves, nor will they allow others to build churches beyond the needs of the parishioners” .

The most important measure in this respect, in particular for the life of the white clergy, is the attempt of Peter “determine the indicated number of sacred church ministers and arrange the church in such a way that a sufficient number of parishioners will be assigned to any one”. By the Synodal Decree of the year, the states of the clergy were established, according to which it was determined “So that there would not be more than three hundred households and in great parishes, but there would be in such a parish, where there is one priest, 100 households or 150, and where there are two, there are 200 or 250. And with three there would be up to 800 households, and with so many priests there weren’t more than two deacons, and the clerks should be according to the order of the priests, that is, with each priest there is one deacon and one sexton ”. This state was supposed to be implemented not immediately, but as the superfluous clergy would die out; the bishops were ordered not to appoint new priests while the old ones were still alive.

Having established the states, Peter also thought about the food of the clergy, who depended on the parishioners for everything. The white clergy lived on what brought them the correction of the need, and with general poverty, and even with the undoubted decrease in adherence to the church at that time, these incomes were very small, and the white clergy of Peter's times were very poor.

Having reduced the number of the white clergy, forbidding and making it difficult for new forces to enter it from the outside, Peter, as it were, closed the clergy within himself. It was then that caste traits, characterized by the obligatory inheritance of the father's place by the son, acquired special significance in the life of the clergy. Upon the death of his father, who served as a priest, his eldest son, who was a deacon under his father, took his place, and the next brother, who served as a deacon, was appointed to the deaconate in his place. The deacon's place was occupied by the third brother, who had previously been a sexton. If there were not enough brothers for all the places, the vacant place was replaced by the son of the elder brother or only credited to him if he did not grow up. This new class was assigned by Peter to pastoral spiritual enlightenment activity according to the Christian law, however, not on the whole will of the understanding of the law by the pastors as they want, but only as the state authority prescribes to understand it.

And heavy duties were assigned to the clergy in this sense by Peter. Under him, the priest not only had to glorify and exalt all the reforms, but also help the government in detecting and catching those who denounced the activities of the king and were hostile to her. If at confession it was revealed that the confessor had committed a crime against the state, was involved in rebellion and malice against the life of the sovereign and his family, then the priest had to, under pain of execution, report such a confessor and his confession to the secular authorities. The clergy were further entrusted with the duty to search for and, with the help of the secular authorities, to pursue and catch schismatics who had evaded paying double taxes. In all such cases, the priest began to act as an official subordinate to the secular authorities: in such cases he acts as one of the police bodies of the state, together with fiscal officers, detectives and watchmen of the Preobrazhensky order and the Secret Chancellery. The denunciation of the priest entails a trial and sometimes cruel reprisals. In this new mandate of the priest, the spiritual nature of his pastoral activity was gradually obscured, and a more or less cold and strong wall of mutual alienation was created between him and the parishioners, and the flock's distrust of the pastor grew. "As a result, the clergy- says N.I. Kedrov, - closed in its exclusive environment, with the heredity of its rank, not refreshed by the influx of fresh forces from outside, gradually had to drop not only its moral influence on society, but itself began to become impoverished in mental and moral forces, to cool, so to speak, to the movement public life and her interests. Not supported by society, which does not have sympathy for him, the clergy in the course of the 18th century is being developed into an obedient and unquestioning instrument of secular power.

The position of the black clergy

Peter clearly did not like the monks. This was a feature of his character, probably formed under the strong influence of early childhood impressions. "Scary scenes, - says Yu.F. Samarin, - met Peter at the cradle and disturbed him all his life. He saw the bloody berdys of the archers, who called themselves the defenders of Orthodoxy, and was accustomed to mixing piety with fanaticism and savagery. In the crowd of rebels on Red Square, black cassocks appeared to him, strange, incendiary sermons reached him, and he was filled with a hostile feeling for monasticism.. Numerous anonymous letters sent out from the monasteries, “accusatory notebooks” and “scriptures”, calling Peter the Antichrist, were distributed to the people in the squares, secretly and openly, by the monks. The case of Empress Evdokia, the case of Tsarevich Alexei could only strengthen his negative attitude towards monasticism, showing how hostile he was. public order power is hidden behind the walls of monasteries.

Under the impression of all this, Peter, in general, in his entire mental make-up, is far from the demands of idealistic contemplation and put uninterrupted practical activities, began to see in the monks only different "zabobons, heresies and superstitions". The monastery, in the eyes of Peter, is a completely superfluous, unnecessary institution, and since it is still a hotbed of unrest and riots, then, in his opinion, is it a harmful institution that would not be better to completely destroy it? But Peter was not enough for such a measure. Very early, however, he began to take care to restrict the monasteries by the most severe restrictive measures, reduce their number, and prevent the emergence of new ones. Every decree of his, relating to monasteries, breathes with the desire to prick the monks, to show both themselves and everyone all the futility, all the uselessness of monastic life. Back in the 1950s, Peter categorically forbade the construction of new monasteries, and in the year he ordered all existing ones to be rewritten in order to establish the states of monasteries. And all further legislation of Peter regarding monasteries is steadily directed towards three goals: to reduce the number of monasteries, to establish difficult conditions for admission to monasticism, and to give monasteries a practical purpose, to derive some practical benefit from their existence. For the sake of the latter, Peter tended to convert monasteries into factories, schools, infirmaries, nursing homes, that is, "useful" state institutions.

The Spiritual Regulations confirmed all these orders and especially attacked the foundation of sketes and hermitage, which is undertaken not for the purpose of spiritual salvation, but “free for the sake of life, to be removed from all power and oversight, and in order to collect money for the newly built skete and take advantage of it”. The regulation included the following rule: “No letters should be written to monks in their cells, either extracts from books or letters of advice to anyone, and according to spiritual and civil regulations, ink and paper should not be kept, because nothing ruins monastic silence like their vain and vain letters ...”.

Further measures were prescribed for the monks to live in monasteries indefinitely, all long-term absences of monks were forbidden, a monk and a nun could only go outside the walls of the monastery for two, three hours, and even then with a written permission from the rector, where the period of vacation of the monastic is written under his signature and seal . At the end of January, Peter published a decree on the rank of monastic, on the appointment of retired soldiers in monasteries and on the establishment of seminaries, hospitals. This decree, finally deciding what to be for monasteries, as usual told why and why a new measure was being taken: monasticism was preserved only for the sake of “the pleasure of those who desire it with a direct conscience”, and for the bishopric, for, according to custom, bishops can only be from the monks. However, a year later, Peter died, and this decree did not have time to enter life in its entirety.