PHYSICAL-GEOGRAPHICAL ZONING (from French rayon - beam, radius) - identification of parts geographical envelope(territories or water areas) that have relative, uniformity, and drawing boundaries between these parts and others that differ from them in one of the natural features or in a combination of them. The degree of generality recognized as sufficient to combine certain territories into one zoning unit is usually the greater, the smaller the allocated units. If R. f.-g. aims to identify areas that are similar in only one component of the landscape (relief, soils, etc.) or a group of closely related components (geological-geomorphological, soil-botanical, hydro-climatic), then it is called. branch (private), if for all the most important components included in the natural complex - landscape.

R. f.-g. serves as a means of identifying and analyzing real spaces, differentiation geogr. shells. However, the methodology for drawing natural boundaries on maps is relatively well developed only for sectoral zoning. Some geographers believe that physical-geographic boundaries in landscape zoning can and should be drawn according to a set of features, since all components of the landscape are interconnected. Others point out that the connections between the components are non-rigid, correlated. character (see Correlation). For example, almost the same vegetation can be distributed on different elements of the relief. Therefore, the places of the most dramatic changes in components in the transition from one unit of R. f.-g. often do not coincide with the other, and the boundaries turn into transitional zones. It is possible to draw linear boundaries objectively and unambiguously only by agreeing on which components or features should be guided at each stage of zoning. Usually on higher levels choose the most important, independent, "leading" features, then move on to dependent on them, "slave". With small-scale R. f.-g. both zonal and azonal classifications are used. signs, although their strict alternation is not necessary; when moving to larger scales, zonal features disappear. In the mountains, the latitudinal zones are drawn in the direction of the equator and concentrated in a small space in the form of narrow broken ribbons; latitudinal zonality becomes more complicated and changes into altitudinal zonality. In such cases, one has to move from zoning by zones on the same scale to zoning “by spectra”, i.e. but the number, composition and order of high-altitude zones. The choice of signs, along which the boundaries are drawn, depends on the purpose of R. f.-g. For broad purposes (teaching geography, maps for geographic descriptions, non-specialized atlases) R. f. -G. produced according to the most common features associated with the genesis of the landscape, such as structural-tekt. differences expressed in relief and lithology, zonal types of soils and reconstructed vegetation, average annual indices and annual course of the main. meteorol. elements, and so on. With a special R. f.-g., although factors characterizing the different sides nature, but only especially important for the chosen purpose; e.g. for s. x-va: repeatability of slope angles and exposures of slopes, the sum of active temperatures, the ratio of solid and liquid precipitation, humus content, mechanical. and the aggregate composition of the soil, etc. The differences between the zoning schemes for different purposes are relatively small at a small scale and increase with its increase.

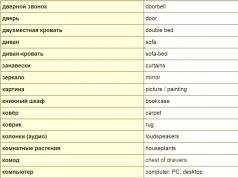

circuit diagram R. f.-g. based on the typological map. A. - primary (for a given scale) contours are identified in the zoned territory. B. - according to the accepted classification, they are marked with areas 1, 2, 3. C - drawing the boundaries of regions with a predominance of one of these types. D - the workload is removed - a regional map is received, the regions are given names 1, 11, 111.

There are two bases. R. f.-g.'s method: typological (which some geographers do not consider regionalization and call it typological. mapping) and individual (regional). A small area of the territory, on the scale of this study, conditionally recognized as homogeneous, “primary”, can serve as a unit of both typological and individual zoning. If further, according to the accepted classification, it is united with all areas similar to it, at least territorially separated from it, then a typological, zoning is obtained. The units allocated during its course are called. types of terrain, or types of landscape, and with sectoral zoning - types of relief, soils, etc. So, Ph.D. specific ravine Vyazovy in typological the legend is combined into one generic concept with all other ravines, and all of them are indicated on the map by one sign. Then, together with beams, valleys, etc., they enter the concept of a higher rank - “erosion forms”, denoted by a range of similar signs, etc. If the “primary” section is combined, on the contrary, only with adjacent sections, although and different, but forming a typical combination of repeating elements of the landscape or a territory with a predominance of one of their types, we get an individual, zoning. The units of zoning distinguished by the latter method are distinguished by their integrity and originality and are called. regions. Thus, the mentioned Vyazovy ravine, together with neighboring gullies, plakoramps, and other ravines that divide them, is included in the Mesopotamia region of the Zushi and Kolpyankp rivers, and the latter - in the Central Russian Upland, etc.

Both typological and individual, zoning in principle always consists of several. steps, which reflects the complexity of the geogr. shells and varying degrees differentiation of its parts. Type-logical units. zoning are named according to the classifications on which they are based. features, for example, geomorphological: plateau, floodplain, etc., geobotanical: steppe, white-wormwood, etc. Landscape units are usually designated according to the most representative feature. Thus, "steppe" can mean not only an association of steppe herbs, but also a type of landscape with a characteristic steppe climate, relief, soils, and fauna. Units of the individual, zoning are designated by proper names, for example: Africa, Meshchera, Dolgaya beam. Here, too, the "Dolgaya gully" can be a unit of both a geomorph and a landscape "individual" zoning. one system taxonomic geographical units of zoning have not yet been established, but the discrepancy in the names and order of taxa (units) is gradually decreasing.

Several are known. R.'s methods f. -G. Nice results gives a method consisting of trace operations. 1. On the basis of reconnaissance on the ground (on a large scale) or the study of literary and cartographic. sources (with small) and taking into account the purpose of zoning, a preliminary classification of terrain types is compiled. At the same time, the number of zoning levels and signs or complexes of interrelated signs are established, to-rye will be used at each step. 2. A legend is being developed - a graph. classification reflection. 3. The boundaries of the contours corresponding to different points of the classification are plotted on the map (Fig., A). 4. The corresponding signs of the legend are put on the contours (Fig., B). 5. Classification and legend are checked and refined on the basis of collected and systematized material. 6. Primary contours are grouped into typological. units of increasing ranks: species, genera, terrain classes (with sectoral zoning - relief, soils, etc.), or into regions: tracts, districts, etc. (Fig., C), after which the primary load can be removed (Fig., D). 7. The ranks of all units are checked "from top to bottom" by following. crushing larger units previously established on small-scale maps. This ensures the comparability and linkage of taxa of the same rank plotted on maps of different localities by different authors. If necessary, regions of any rank can also be combined into types (types of tracts, districts, regions, etc.). Another common method of landscape zoning is the imposition of sectoral typologies. cards to one another. In this case, the contours obtained when crossing boundaries of various kinds, internally homogeneous in all mapped features, are taken as the primary units of landscape zoning of a given scale. Operations 3-7 are performed as in the previous case. Sometimes genetic and morphological methods of R. f.-g. are distinguished, but, as a rule, they coincide, since in nature the same combinations of processes lead to the formation identical shapes. R. f.-g. is always accompanied by a characteristic of the allocated units. Its most concise form is a simple legend, more complete - a table legend and a text description. R. f.-g. enters as milestone in each fn.-geogr. study. Soviet geographers are conducting extensive work on R. f.-g. different scales. At Min-ve higher. Education of the USSR established the Coordinating Commission for Natural and Ekon.-geogr. zoning of the USSR, which unites the work in this industry of all universities. Important works on R. f.-g. are also performed in the Institute of Geography of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, SOPS of the State Economic Council, and other scientific. institutions. R. f.-g. helps to understand the processes that resulted in the emergence and development of the existing types of landscapes on Earth. It is used as the basis of economics. zoning and adm. division, for the needs of x-va, transport, building, for planning correct use prmroZnyz; resources and activities to transform nature.

Lit .: Strumilin S. G. and Lupinovich I. S., Natural-historical regionalization of the USSR, M.-L., 1947; Shchukin Y. S., Some Thoughts on the Essence and Methodology of Complex Physical-Geographical Regionalization of Territories, “Vopr. Geography", 1947, Sat. 3; Armand D. L., Principles of physical-geographical zoning, “Izv. Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Ser. Geogr.", 1952, No. 1; Isachenko A. G., Basic questions of physical geography, L., 1953; Prokaov V.I., On some issues of the methodology of physical-geographical zoning, “Izv. Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Ser. geogr.", 1955, Ag" 5; Milkov F.N., Physical-geographical region and its content, M., 1956; Letunov P. A., Principles of integrated natural zoning for development Agriculture, "Soil science", 1956, L "3; Sochava V. B., Principles of physical-geographical zoning, in the book: Questions of Geography. Sat. Art. for XVIII International geogr. congress, M.-L., 1956; "Quest. Geography", 195G, Sat. 39; 1961, [sat. 55]; Solntsev N.A., On some fundamental issues of the problem of physical-geographical zoning, “Nauchi, dokl. high school. Geological and geographic science", 1958, JNj 2; Materials for the III Congress of the Geographic Society USSR. Reports on the problem - Natural zoning of the country for the purposes of agriculture, L., 1959; Rhodom n B. B., On elementary, synthetic and complex maps, “Izv. Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Ser. geogr.", 1959, K 4; R and x-ter G. D., Natural regionalization, in collection: Soviet geography, M., 1960; Physical-geographical zoning of the USSR. Sat., M., 1960; Grigoriev A. A., On some basic problems of physical geography, “Izv. Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Ser. geogr.", 1957, JVs 6; Efremov Yu. K., Two logical stages in the process of physical-geographical zoning, Vesti. Moscow State University, 1960, No. 4; Mikhailov N. I., Physical-geographical regionalization, part 3, M., 1960.

Remember in which geographical zone Ukraine is located.

What kind natural areas common in its area?

THE CONCEPT OF REGIONING. All the diversity of landscapes creates a landscape (geographical) shell of the Earth, which “envelops” our planet with a thin layer.

Between the landscape shell as a planetary natural complex and landscapes as its smallest parts, there is a system of regional natural complexes (RC). They occupy different territories. One of the tasks of geography is their identification, determination of boundaries, study and mapping, that is, the implementation of physical and geographical zoning.

Considering the components and factors of landscape development, you probably noticed that some of them are zonal, while others are non-zonal. Zonal include those that are distributed on the earth's surface in accordance with the laws of geographic (latitudinal) zoning - stripes that replace each other from the equator to the poles. The amount of solar energy, the distribution of heat and moisture, and the soil and vegetation cover change zonally. Non-zonal (azonal) are those factors and components of the landscape, the location of which does not depend on geographic latitude.

This is primarily a geological structure and relief. In accordance with this, regional natural complexes are also divided into zonal and azonal (Fig. 135).

So, zonal natural complexes are PCs formed as a result of latitudinal manifestation natural processes and phenomena. These are geographical zones, natural zones and subzones. The largest azonal natural complexes are the PCs of the continents and oceans, and within their limits, the physical-geographical countries and natural-aquatic complexes of the seas. Physical-geographical countries and zones are divided into smaller regional PCs, which are distinguished by a combination of zonal and azonal factors. These include physical-geographical territories, regions and districts.

PHYSICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL ZONING OF UKRAINE. The largest zonal parts of the landscape envelope are geographical zones. They are distinguished by the amount of solar energy received and the characteristics of the circulation of air masses. Ukraine is located almost entirely within the temperate geographical zone of the Northern Hemisphere and only on the southern slope Crimean mountains and south coast Crimea natural conditions have features of the subtropical zone.

Due to differences in the distribution of heat and moisture within the belt, natural zones are formed with their own climate, soils, vegetation and wildlife. In Ukraine, these are zones of mixed forests, broad-leaved forests, forest-steppe and steppe (Fig. 136). Of course, natural zones are typical only for the flat part of the country, where latitudinal zonality is clearly manifested. They do not exist in the mountains: there the interaction of natural components occurs according to the laws of altitudinal zonation, that is, in bands that replace each other with height.

Within natural zones, there are often significant differences in the moistening of territories and the flow of heat. This causes a variety of soil and vegetation cover, and therefore natural zones can be divided into subzones. In Ukraine, such a division is typical for the steppe zone, in which the north-steppe, middle-steppe and south-steppe subzones are distinguished.

The largest azonal zoning units on land are physiographic countries - natural complexes formed within large tectonic structures (platforms, folded structures), which correspond to large landforms (plains, mountain systems). Therefore, among the physical-geographical countries, flat and mountainous ones are distinguished. Ukraine is located within three physical and geographical countries: the East European Plain (its southwestern part), the Carpathian Mountains (its middle part) and the Crimean Mountains (Fig. 137). In the south, the territory of Ukraine goes to the natural aquatic complexes of the Black and Azov Seas.

A physical-geographical region is a part of a natural zone or subzone within a flat country or part of a mountainous country. The main reasons for the selection of edges are heterogeneity geological structure and relief, as well as the remoteness of the territory from the oceans, which causes a change in the continentality of the climate. For example, in the forest-steppe zone, three physical and geographical regions are distinguished: the Dniester-Dnieper (within parts of the Podolsk and Dnieper uplands), the Left-Bank-Dnieper

Provsky (on the Dnieper lowland) and Central Russian (on the slopes of the hill of the same name). Several physiographic regions are also distinguished in the subzones of the steppe zone. But each of the two forest zones forms a separate large physical-geographic region: the zone of mixed forests - Ukrainian Polissya, the zone of broad-leaved forests - the Western Ukrainian region. Each of the mountainous countries is also represented in Ukraine by one physical and geographical region - the Ukrainian Carpathians and the Crimean mountainous region. In total, 14 regions are distinguished in Ukraine.

Within the limits of the regions, there are differences in natural conditions associated with the unequal geological and geomorphological structure of the territories. This is the reason for the allocation of even smaller regional natural complexes - physical-geographical regions and physical-geographical regions.

Physical-geographical zoning has great importance for the knowledge of natural processes and phenomena, economic activity and environmental work. Having established the limits of this or that landscape and having studied its structure and connections, it is possible to substantiate rational nature management in it, to determine measures to improve environmental situation, to establish the territories in which it is desirable to carry out environmental activities.

REMEMBER

Physical-geographical (landscape) zoning is the definition of the boundaries of regional natural complexes, which are a combination of similar landscapes in certain areas.

Zonal units of physical-geographical zoning are geographical zones, natural zones and subzones, azonal units are physical-geographical countries and natural-aquatic complexes of the seas. Ukraine is located within three physical-geographical countries (East European Plain, Carpathian and Crimean Mountains) and four natural zones (mixed forests, deciduous forests, forest-steppe and steppe).

QUESTIONS AND TASKS

1. Name the system of units of physical and geographical zoning of Ukraine,

2. How do zonal PCs differ from azonal PCs?

3. Within what natural zones is Ukraine located?

4. What major azonal PCs are distinguished within Ukraine?

5*.Compare the units of the physical-geographical zoning of Ukraine within the forest, forest-steppe and steppe zones (number, size, types).

This is textbook material.

First, it is necessary to clarify the meaning of the term "physico-geographical zoning". A number of authors call it natural or landscape or use these terms as synonyms. We attach special importance to each of them.

Under natural zoning in accordance with broad sense the word "natural" we understand the selection and definition taxonomic rank individual territorial units similar in terms of any natural sign(s). Consequently, natural zoning includes both physical-geographical and private zoning in the meaning adopted above. In addition, the composition of natural zoning includes the division of territories according to even more particular features - individual aspects or properties of the components (for example, forest seed zoning - the allocation of territorial units according to the yield and good quality of seeds tree species). A broad understanding of natural zoning is necessary to oppose it to non-natural, carried out according to certain socio-economic characteristics.

Landscape zoning, in our understanding, is an integral part of the physical-geographical; this is the selection and determination of the taxonomic rank of landscape HAs. It is hardly correct to call any HA selection landscape, including one-sided ones that differ significantly from landscape ones. In addition to landscape, we consider tectogenic and climatogenic zoning as special types of physical-geographical zoning; the latter is subdivided into zonal, sectoral, barrier and altitudinal.

The question of the appointment of physical-geographical zoning is considered earlier, its principles and methods, because not only some features of its methodology, but even its individual principles depend on the purpose of zoning. By purpose, physical-geographical zoning is divided into general scientific and specialized, or applied. The first is not connected with the solution of any particular practical problem; the second, on the contrary, is carried out to solve or scientifically substantiate the solution of just such a problem.

General scientific zoning is primarily of scientific importance. This already follows from the fact that landscape science is the science of GCs, which stand out during general scientific zoning. But it also has practical value. After all, each GC shown on the zoning map and described in the text description has a special natural potential. Naturally, rational economic and any other (for example, recreational) use of the natural resources of any territory is impossible without taking into account the natural potential of the GCs that compose it.

However, the results of general scientific zoning, i.e., its map and its description, usually cannot be used directly to solve specific practical problems, since the sections of maps of general scientific and applied zoning often do not coincide with each other. The reason is that natural similarities and differences, according to which applied units are distinguished and which are the main ones in solving a given practical problem, do not always play a leading role in general scientific regionalization.

Nevertheless, maps of general scientific zoning can serve as a scientific basis for applied zoning, because there is a certain connection between them: the units of applied zoning usually “without a trace” fit into the units of general scientific zoning, and four main types of relationships are possible between these units (Fig. 4): 1) unit applied zoning consists of one unit of general scientific zoning of comparable rank; 2) the applied unit also corresponds to one general scientific, but of a lower rank; 3) an applied unit is composed of two or more general scientific units of comparable rank; 4) an applied unit consists of two or more general scientific units of a lower rank.

Consequently, on the basis of general scientific zoning materials, it is possible to draw up a map of applied zoning. To this end, it is necessary to analyze general scientific materials from the point of view of this practical task and, by combining general scientific units of a certain rank or dividing them into units of a lower rank, identify units of applied zoning. This work is especially effective if it is carried out by an appropriate specialist together with a landscape specialist. True, a map of applied zoning compiled on the basis of general scientific materials is usually of a preliminary nature and requires special cameral or even field studies for its clarification. However, the volume of these studies is relatively small, since it is enough to reveal what is lacking in general scientific materials.

Specialized zoning is possible without the General Scientific Basis. However, in this case, it should be preceded by a study of natural similarities and differences and the GCs associated with them. Such forced studies, especially if they are carried out by non-landscape scientists, are usually much inferior in their scientific and methodological level to special studies for the purposes of general scientific zoning, and are characterized by insufficient completeness and uniformity. Therefore, it is impossible or very difficult to use them for solving scientific and applied problems. Consequently, the lack of a general scientific basis for specialized zoning leads to waste of time and money. (This looks about the same as if there were no state topographic maps which have a wide purpose, and to solve each specific practical task of using the resources of the territory, it would be necessary to conduct its topographic survey again in order to prepare the topographic basis necessary for applied research.)

Thus, general scientific zoning responds to the demands of practice indirectly- through specialized zoning. In this case, an abbreviated version of the considered method for the practical use of materials from general scientific zoning is often used. It consists in the fact that they are limited only to their analysis from the point of view of a given applied problem and the identification of properties of the HA, favorable and unfavorable for its successful solution. So does, for example, VB Sochava (1975), assessing the natural conditions of the strip along the Baikal-Amur Mainline (BAM) for the purpose of its economic development. Therefore, in this case, only the first part of the actions related to this method is performed, while the second part - the compilation of a map of applied zoning - drops out. This version of the method is used, for example, when a practical problem can be solved without this card.

Only a series of general scientific maps on which GCs of all types and ranks are identified can fully fulfill the function of a scientific basis for various types of applied zoning. Such maps should be at the modern scientific and methodological level. They need to be constantly improved by using the results of the latest industry and comprehensive research. Adjustments must be made to the textual characteristics of the Civil Code; in addition, these characteristics are complemented by indicators needed to solve new practical problems.

The considered concepts of general scientific and applied regionalization are close to the most common in Soviet geography. However, there are individual researchers who deny the general scientific physical-geographical zoning. These include, first of all, D. L. Armand (1970, 1975). He actually denies the existence of the GC, because he recognizes only their "cores of typicality", which, in his opinion, are small in size and do not even give an idea of the shape of the GC. These nuclei are separated by such gradual transitions that the HAs seem to overflow into each other. The discrepancy between the boundaries of private regions in the wide transitional strips between the Civil Code does not allow one to unequivocally decide which of them to accept as the border of the Civil Code, if the purpose of zoning is unknown. And the latter, according to D. L. Armand, can take place only with applied zoning.

Indeed, transitional bands between neighboring GCs can sometimes occupy a significant part of each of them. However, even in this case, more or less typical areas, for which there is no doubt as to which GC they belong to, prevail over their area. If the picture drawn by D. L. Armand had been correct, then the very idea of GCs could hardly have arisen, and their boundaries would not have been visible either on aerial photographs (low-ranking GCs) or on space photographs. But the latter show the boundaries of even zonal GCs, the most vague of the physical-geographical boundaries, as a result of which it is possible to study land zonation from satellite images (Vinogradov, Kondratiev, 1970).

DL Armand is right that comparability of regionalization results is unattainable if it is not purposeful. But after all, the intended purpose can be wide, which is just characteristic of general scientific zoning (the basis for various kinds applied). As will be shown below, such a broad purpose of physical-geographical zoning by no means excludes its comparable results. (For more details see: Prokaev, 1971.)

In the following sections of this chapter and chapters III-VII, questions of general scientific physical-geographical zoning and regionalization close to it for educational purposes are discussed, and for brevity, the adjectives "general scientific" and sometimes "physical-geographical" are omitted. Chapter IX is devoted to the use of zoning materials for solving practical problems.

Any large object is difficult to study as a whole - it must be divided into parts. (Of course, having studied each part separately, you then have to “fold” them again in order to see the object in its unity.) So it is difficult to understand the geography of Russia “at once and all”, therefore the vast expanse of our country is traditionally divided into regions - regionalization is carried out.

The word "zoning" in Russian has two meanings: firstly, it is the process of dividing the territory into parts and, secondly, the result of this process is a grid of districts.

How can regionalization be carried out?

Remember how you had to divide the territory into parts, getting acquainted with the nature and population of Russia. For example, studying the relief, you learned that the territory of our country is divided into low-lying western and elevated eastern parts, and upon closer examination, you saw separate lowlands, uplands, and mountains. Studying the climate, you singled out several climatic zones, studying soils - various soil zones, etc. These were the divisions of the territory according to one of the components of nature. And the allocation of natural zones is already a division according to several criteria at the same time.

AT economic geography also used is the division of the territory into parts that are homogeneous in some respect, for example, into zones with the same set of cultivated crops, with similar occupations of the population, etc. But more often, economic regions are distinguished by connections, by the attraction of territories to each other.

Rice. 5. Such a different Russia

Our textbook will use both natural and economic zoning. At the same time, in order to show the interaction of nature, population and economy within a particular territory, we will use such a concept as a geographical area.

Geographic area- a historically developed territory, distinguished by the peculiarities of nature, population and economic specialization.

We will study such geographical areas as Central Russia, the European North, the North-West, the European South ( North Caucasus), the Volga region, the Urals, that is European part Russia, as well as Western Siberia, Eastern Siberia, Far East, that is, the Asian part of Russia.

Some of the geographic areas may include part of a natural area and several economic areas. For example, Central

Russia is the center of the East European Plain, uniting the Central, Volga-Vyatka, Central Black Earth economic regions.

The Ural geographical region includes part of the Ural natural region (Middle and Southern Urals) and coincides with the boundaries of the Ural economic region. And Eastern Siberia, on the contrary, combines two natural regions - Central Siberia and the mountain belt of southern Siberia.

Rice. 6. Natural regions of Russia

Compare two types of zoning of our country - natural and economic (economic). The boundaries of economic regions always coincide with the boundaries of the subjects of the Federation (any region or republic is included in only one region!), while the boundaries of natural regions do not coincide. At the same time, natural and economic regions sometimes bear the same names, for example, Western Siberia.

Rice. 7. Geographical and economic regions of Russia

- Compare the boundaries of natural, economic and geographical areas. Determine which natural and economic areas are included in each of the geographical areas.

- How do you think, how to explain that the boundaries of economic regions necessarily coincide with the boundaries of the subjects of the Federation, but the boundaries of natural regions do not coincide?

- How can one explain the fact that there are more economic regions on the East European Plain than in the Asian part of Russia?

What are the features of the administrative-territorial structure of Russia?

One of the types of zoning is administrative-territorial division, that is, the division of the country's territory into administrative units: regions, territories, districts, etc. Such a division is necessary for any modern state in order to collect taxes, maintain order, take care of education and healthcare, call up for military service, or at least just deliver mail.

At different periods of its history, our country was divided into very different parts. These were principalities, voivodeships, governorships, provinces, regions, territories, etc.

The modern administrative-territorial division of Russia - a consequence state structure our country. Russia - federal state, consisting of 89 regions - subjects of the Federation (Fig. 8).

Rice. 8. Administrative-territorial division of Russia (2001)

In 2000, by presidential decree, in order to strengthen the effectiveness of the federal state power all subjects Russian Federation were united into seven federal districts: North-Western, Central, Volga, Southern, Ural, Siberian and Far East. The boundaries of federal districts do not always coincide with the boundaries of economic regions. Federal districts headed by plenipotentiaries of the President, who must monitor compliance Russian legislation, including bringing local laws (adopted in the region, republic, etc.) into line with federal ones.

conclusions

Different types of zoning of the country's territory are carried out with different goals. One of the tasks is to highlight the specific features of a geographical area that distinguish it from others (by geographical location, features of nature and resources, population, existing links within the region and with other territories). On this basis, a holistic image of each region is created. A special type of zoning is an administrative-territorial division necessary for the existence of any state, especially such a huge one as Russia.

Questions and tasks

- What types of regionalization are discussed in the text? What tasks do they solve?

- Draw up a scheme of subordination of the administrative-territorial division of your district (from the street to the subject of the Federation).

- Find out what is the administrative-territorial division of other countries of the world, for example, the USA, Germany, France, India, China. What are the characteristics on which it is based? Compare it with the administrative-territorial division of Russia.

- Using the knowledge already gained about the nature and population of Russia, think about what areas you yourself would divide our country according to the features that seem significant to you.

Geographic zoning

The origins of zoning and landscape science were laid down a long time ago. More V.V. Dokuchaev, studying different character soils, drew attention to the planetary diversity of nature depending on the latitudinal location of the terrain, that is, in fact, to the dependence of changes in nature on the nature of the influence solar radiation. He identified natural areas, based on which, later (1913) L.S. Berg singled out landscape zones and regions. A number of Russian researchers back in 1910 based the allocation of regions (zones) on a climatic sign, and areas, as smaller units, on a sign of soil / Milkov, 1966, p. 14 /.

In the post-war period, attention to the issues of landscape and landscape science has especially increased. During 1953-1963, six all-Union conferences on issues of landscape science were held in the USSR. Even then, two different approaches to understanding the landscape and zoning developed. Some researchers (S.V. Kalesnik, F.N. Milkov, A.G. Isachenko, V.B. Sochava) defined physical-geographical zoning as a manifestation of landscape complexes of different taxonomic ranks. Another point of view was held by N.A. Solntsev and his followers, according to which landscape science studies only the lowest landscape complexes - landscapes (regions) and their constituent parts. Provinces, zones, countries are not the subject of study of landscape science, but of regional natural geography / Milkov, 1966, p. 31 /. The reason for these discrepancies was the different definitions of the concept of landscape.

According to F.N. Milkov, the highest units of physical-geographical zoning are the mainland and the geographical belt. Next comes the physical-geographical country (“ part of the mainland that has the geological and morphological unity of the territory, the commonality of microclimatic processes, a certain plan of latitudinal zonality and altitudinal zonality of landscapes" / 1966, p. 66 /). Physical-geographical countries are divided into zonal regions, and those, in turn, into provinces and districts /ibid., p.225/. It should be noted that this author did not consider the physical-geographical zone as a unit of physical-geographical zoning in the form in which V.V. Dokuchaev. Instead, he introduced the concept of "zonal area", which is a segment of the physical-geographical zone within the country /ibid., p.77/. Province according to F.N. Milkov is a system of interconnected physical and geographical regions. And the physical-geographical region is a large isolated part of the province, which has characteristic combinations of soils and plant groups /ibid., p.107/.

These are the so-called obligatory units of physical-geographical zoning. In addition, there are also optional units, which in each case may not be. To them F.N. Milkov attributed "groups of countries", "subzones" or "bands", etc. / ibid., p. 225 /. Thus, according to F.N. Milkov noted the following hierarchy of a single physical-geographical zoning: mainland - belt - zonal region - province - district. Here, within Ukraine, there is a border between two physical and geographical countries: the Russian Plain and the Carpathian mountainous country; two zonal areas: steppe and forest-steppe, in which several provinces can be distinguished: in the forest-steppe - the Volyn-Podolsk and Dnieper uplift, the Dnieper lowland and the province of the Donetsk Ridge, in the steppe - the Black Sea lowland / Milkov, 1966, p. 102 /.

F.N. Milkov also opposed the opinion of N.A. Solntsev and his supporters that neither a physical-geographical zone nor a zonal region can be units of physical-geographical zoning, since they do not constitute a single whole on a lithogenic basis. He believed that N.A. Solntsev is right only if the problem of physical-geographical zoning is reduced to the allocation of geological-morphological complexes /ibid., pp.71-72/. If, however, by physical-geographical zoning we mean a territorial community with a single genetic basis, homogeneous natural complexes, etc., then the lithogenic basis for this should not play important role/ibid., p.35/.

The above question is very important, since here we are talking about two very serious factors on which the natural differentiation of the Earth depends. It is another matter whether to apply them as basic principles for distinguishing one or two different hierarchical series of the natural differentiation of the earth's shell. In fact, F.N. Milkov, hierarchical units are distinguished on the basis of different principles: the continent is a purely physical concept, as a separate most of sushi; belt - the latitudinal division of this land according to the principle of the amount of solar energy; country - already has a geological and morphological unity; the zonal region, not having such unity, nevertheless stands out according to the principle of a different distribution of solar energy in the latitudinal direction, however, it is separated within the country, that is, within the framework outlined by the geological and morphological basis; the province is distinguished according to the principle of peculiarities of longitude-climatic and oro-geomorphological conditions; and, finally, the area, as we have already seen, has geomorphological and climatic features, that is, in fact, what the landscape is according to N.A. Solntsev. Thus, F.N. Milkov essentially agrees with A.G. Isachenko, who considers the doctrine of landscape and physical-geographical zoning as two different departments of landscape science in its broadest sense /Milkov, 1966, p.31/.

Other experts divide the entire geographic shell of the Earth into the world's oceans and land. The land is divided into continents, within which countries are distinguished. Within the plain countries, zones are distinguished, within which provinces are designated. A physical-geographical region is a section of a province - it is a combination of genera and types of landscape, and smaller taxonomic units are already distinguished in the landscape: tracts and facies /Mikhailov, 1985, p.92, 96/.

In general, the division of the earth's surface by geographers into certain territorial areas is mainly influenced by two types of factors: zonal and azonal. Zonal factors affect changes in the nature of the earth's surface in the direction from the equator to the poles, due to a change in the angle of inclination of the sun's rays to the Earth's surface. Azonal depend on other reasons, one of them can be considered the lithogenic basis of the earth's surface. Everything on Earth that depends on the distribution of solar energy is zonal, and everything that depends on endogenous forces is azonal. In the structure of the earth's shell, zonal and azonal factors are inconsistently united and inseparable /Kalesnik, 1970, p.165/.

At the same time, it is believed that zoning in pure form is relatively rare, since natural complexes (landscapes) are more dependent on the ratio of heat and humidity than on geographic latitude /Richter, 1964, p.60-61/. This may be due to the fact that the distribution of radiation received by the Earth is decisively influenced not only by the angle of inclination of the sun's rays, but also by the duration of illumination and the transparency of the atmosphere, in particular, cloudiness /ibid., p.57/.

Zoning on Earth is due to planetary-cosmic or astronomical reasons. The azonality is based on the historical tectonic development of the Earth - tectogenesis, one of the manifestations of which is the surface topography /Isachenko, 1965, p.49,82,87/. Azonal and zonal factors act simultaneously, and all nature, including man, as a part of it, depends on them. All modern landscapes are the result of the interaction of zonal and azonal factors in the process historical development geographical envelope. But the landscape in the system of physical-geographical zoning occupies the lowest link /ibid., p.111-113/.

Thus, landscapes are an integral part of both the zonal series of zoning and the azonal series. The boundaries between landscapes are sometimes very clear, but often blurred. Rivers, as a rule, are very clear outlines of the boundaries of landscapes, since many of them flow through the boundaries of different morphostructural units of the earth's surface. Therefore, often landscapes within azonal regions are more closely related to each other than within a zone or subzone. So, for example, the steppe and forest-steppe landscapes of the Upper Trans-Volga region are in many respects closer to each other than, say, the forest-steppe landscapes of the Upper Trans-Volga region and Volyn-Podolia / Isachenko, 1965, p. 266 /.

From the foregoing, we can conclude that it is more rational to use the azonal division of the Earth's surface to establish the nature of the activity of human communities. It can be said that zonal factors are of great importance when considering these issues on a larger scale, and for a more detailed consideration of them, azonal factors are needed. For example, the zoning of the nature of the trans-Ural plains is based on a morphostructural analysis of the earth's crust. The West Siberian physical and geographical country is located on a plain, the basis of which is the West Siberian plate. The Central Kazakhstan shield, marked on the surface with a small hillock, is also a physical and geographical country. The Irtysh syneclise - a plain, is considered a province, just like the Kokchetav block - an uplift or the Tengiz trough - a plain /Nikolaev, 1979, p.24/.

Thus, it can be assumed that physical-geographical zoning is based on real differences in nature, and is not the result of a purely scientific construction. This was the opinion of the majority of Soviet geographers /Mikhailov, 1985, p.71/. Moreover, next to the physical-geographical, they consider climatic, hydrological, soil, geobotanical and zoogeographic zoning /Fedina, 1973, p.7/. However, there are opposing opinions among scientists in the world regarding this. So, in America they do not recognize physical-geographical zoning, because they do not recognize the objectivity of the existence of complex natural regions /ibid., p.20/.

It is interesting that when zoning, the main criterion is not the similarity of landscapes, but communication, spatial relations, territorial unity of the constituent parts, and the commonality of their historical development /Isachenko, Shlyapnikov, 1989, p.7/. And the main disputes concerning zoning occur around the problem of the boundaries of certain natural complexes. The question is whether they can be considered quite clear and real or not? In order to imagine the essence of these discrepancies in more detail, let us turn to the question of the natural-territorial complex or, as it is more often called, to the landscape, which is the basis for zoning in geography.